In Chengdu, Kung Fu Tea Is Torn Between Tradition and Performance

A martial arts-influenced style of pouring tea is catching on in China.

BY JORDAN PORTER JUNE 20, 2019

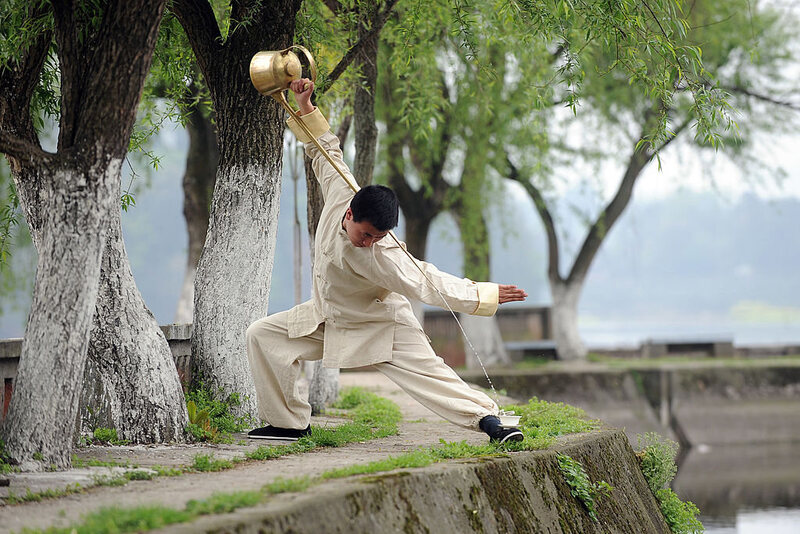

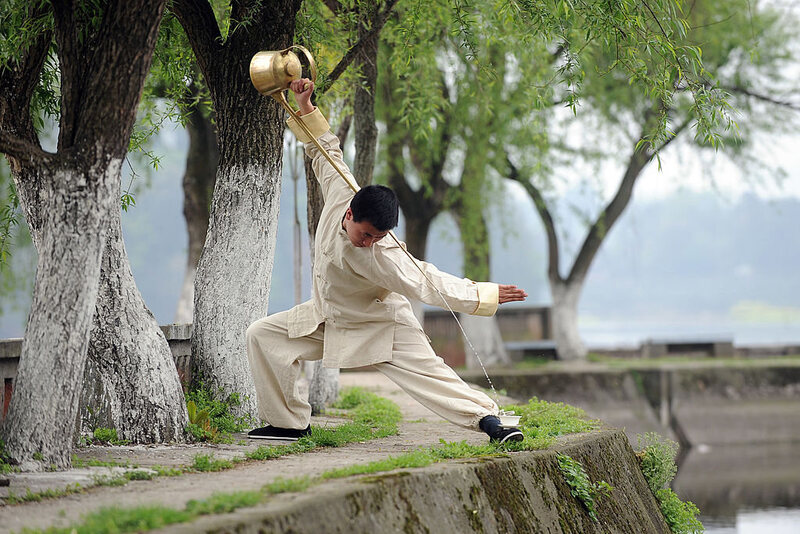

Performances with copper kettles are becoming increasingly popular attractions in Chengdu. CHINA PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES

KUNG FU TEA MASTER ZENG Xiao Long sits humbly in a small tea room, inside a massive courtyard in Chengdu. Dressed up in stone and bamboo to resemble an ancient Chinese village, the courtyard features an outdoor teahouse, a canteen, a public vegetable garden, and a handful of peacocks to complete the aesthetic. “When you say kung fu tea, you probably don’t mean what we do when we say kung fu tea,” Zeng says, pouring hot water over tea leaves in a gaiwan, or three-piece tea cup. Using the lid to hold the leaves back, he pours the tea into a small glass decanter, and then into thimble-sized teacups.

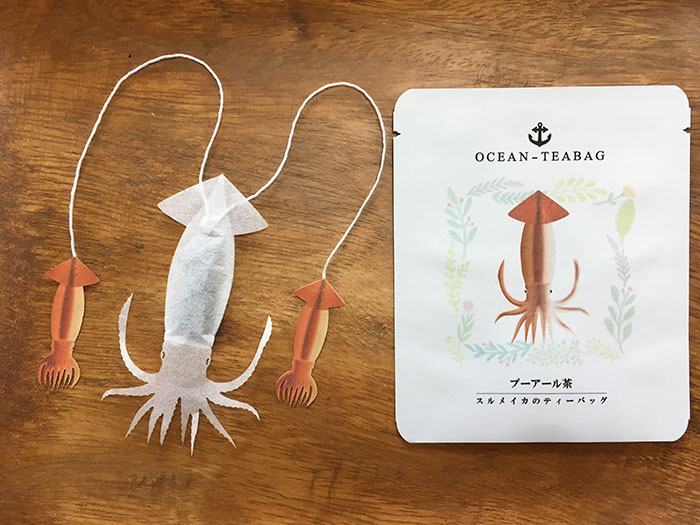

“This is also kung fu tea. In fact, this is what it really is,” he says. “You are probably talking about the long-spout teapot performance.” He motions to the banged-up copper teapots with spouts two or three feet long, leaning against the wall behind him. A small group of Chinese tourists enter the room, which serves as Zeng’s office. The leader introduces Zeng as the country’s most famous and best long-spout teapot performer. She doesn’t mention that he is also this art’s creator and one of its original ambassadors.

Chengdu today is famous for its long-spout teapot performances. In theaters, boisterous restaurants, and touristy performance areas throughout the city, young men and women perform martial arts sequences, acrobatics, and dances, all while daringly twirling, throwing, and spinning long-spout teapots around their heads and bodies. The vibrant copper pots are filled with hot water, which dramatically makes its way into the teacups of lucky patrons.

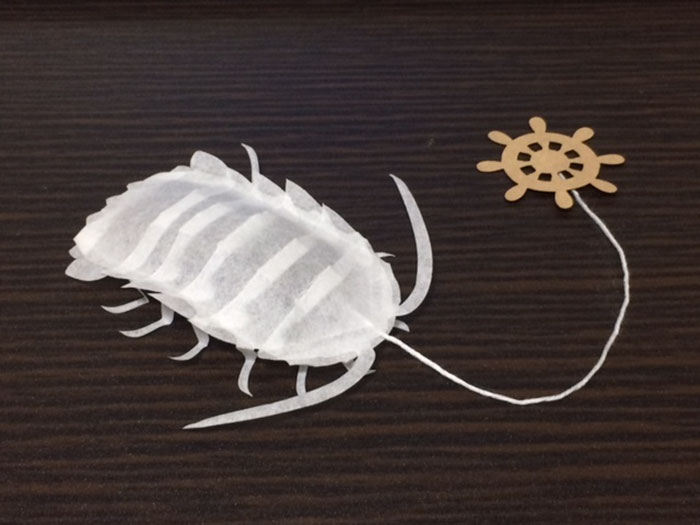

This is often called kung fu tea, but it is not in fact martial in its art or origins. Only a few true wushu moves make their way into the choreography. The word kung fu (功夫), in most cases, refers to arts or disciplines mastered through hard work and diligence, where a greater understanding is ultimately achieved. In this way, it also refers to the ancient Daoist tea ceremony. Disciples study for years to properly perform this much less dramatic ceremony, which emphasizes restraint, subtle hand movements, and tea sets that are petite and pretty. This type of tea ceremony is often viewed as a form of meditation, and it’s the more widely known version of kung fu tea.

Subtle movements and elegant tea sets are a feature of traditional kung fu tea. ALEKSEI POPOV/ALAMY

Long before Zeng twirled pointed copper pots and performed acrobatics, he knew little of tea or of kung fu. He was born in 1977 into a farming family in the Da Zhou region of Sichuan, east of Chengdu. He explains that in this mountainous region, people lived and worked in long, narrow buildings built into the hills. In local teahouses, cramped spaces made long-spout teapots a necessity, so patrons wouldn’t be moved or interrupted by the reach of the waiters refilling their cups with hot water. While long-spout teapots were a local custom, the young Zeng wasn’t very interested in tea. He moved to Chengdu to work in a restaurant, and found himself barely scraping by in the big city. A job ad for a tea master caught his eye with its lofty salary, inspiring him to throw in his table-cleaning towel and buy a long-spouted teapot.

At this point, the long-spout teapot performance did not exist. There were, however, contests where participants gracefully performed the original kung fu tea. But “there was really only one motion for pouring tea from a long spout,” Zeng says. Without a background in the arts, martial or otherwise, Zeng developed his own idea of what a tea performance should be, incorporating elements of tai chi and kung fu from TV and performers he’d seen. In 1999, he entered a tea ceremony competition, and with his unique movements and flare took second place. While there were objections over his flamboyance, a new tradition was born.

A group of young tea-servers learn the long-spout teapot performance. CHINA PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES

Soon, Zeng and a small group of fellow performers began meeting to develop new, more athletic, and spectacular tea-pouring movements. They grew in popularity, with Zeng making a series of high-profile TV appearances, including a performance during China’s 2013 New Year’s Gala which thrust him into national fame. Zeng notes that while some of the others are still involved in the tea industry, he is the only one who stuck with performing. With his growing celebrity status, students sought him out as a teacher.

While kung fu tea as a cultural performance is a relatively new phenomenon in Sichuan, the history of tea here is deep and rich. Mengding Mountain, just 120 miles east of Chengdu, is traditionally considered the place where tea was first cultivated some 2,000 years ago. And tea house culture, whether featuring the short-spouted teapots of the Chengdu plain or the long-spouted ones of the mountains, is an essential part of the region’s identity. “A tea house is a little Chengdu, and Chengdu is a big tea house,” author Di Wang notes in the opening of his book The Teahouse: Small Business, Everyday Culture, and Public Politics in Chengdu. Today in Chengdu, there are over 13,000 tea houses serving as the spots for local gossip and information exchange, as well as rest stops for tourists basking in the beauty of Chengdu’s famous leisurely lifestyle.

A typical, bustling Chengdu teahouse, sans any long-spout teapots. RYAN PYLE/GETTY IMAGES

For the most part, tea culture in Chengdu is unpretentious, more the setting for socializing than the high art of the tea ceremony. But Wu Bo, a young local tea master, worries that the sensational nature of the long-spout tea performance belittles the art of tea itself. She says the performers often understand very little about tea, its history, and its culture. “Some of them don’t even use hot water, it’s just a dance,” she says. “And for many, it’s not about tea, it’s just a job.” To her, true kung fu tea is the opposite of performance, and almost minimalist in its expression. “You can spend all your money on fancy teaware, or learn special movements, but a real tea master can make great tea in anything,” she says.

But performance plays an important role in modern Chinese travel, and cultural displays are consumed voraciously by domestic tourists. Travelers don historical or regionally specific clothing for photo-ops at recreated historic sites to celebrate their history. Even on television, cultural performances and costumed dances entice tourists to new places where they can do more than sightsee. According to Claudia Huang, a Chengdu-born cultural anthropology PhD, performance represents a more meaningful form of consumption for young Chinese people than the purchase of commodities. “This phenomenon of performance serves as a way to celebrate and glorify China’s own cultural history, in a quick and easily digestible way,” she says.

While long-spout teapots are traditional, performing with them is fairly new. CHINA PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES

Zeng’s style of kung fu tea has certainly become a calling card of the city of Chengdu, and synonymous throughout China with Sichuan tea culture. However, he fears that performance itself is not enough to give the art meaning, and actively takes time to pursue the study of tea. He requires his disciples to study as well, sometimes forcing them away from their athletic training to sit down and actually learn how to pour. “I feel a responsibility,” he says. “I am the creator of the long-spout teapot performance. I need to make sure my students learn about the real kung fu tea as well.”

He echoes Wu Bo’s sentiments that most young people study kung fu tea so they can make money. Zeng has hundreds of disciples. For more than 80 percent, he says, this will just be a job. “The market is good right now, there is a big need for performers, and after only a few months of practice you can earn a good wage for performances,” he says. Someday, he believes, there will be a ceiling. Wages will fall, and fewer and fewer people will choose to study this new art.

All but retired from performing, Zeng sits in his office and sips tea from a small cup, his gaze drifting towards the future. “It is my dream to build a tea house some day, where the long-spout teapots can also find their place again off the stage and are used in their original fashion,” he says: simply to pour tea.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61481407/cheesetea_shutterstock.0.jpg)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote