Zhonggong: The “Cult” That Refused to Die

12/16/2020 MASSIMO INTROVIGNE

Hundreds of police hunt for a new incarnation of a group the CCP believed it had successfully eradicated in 2016.

by Massimo Introvigne

A devotional image of the current leader of Zhonggong’s largest branch, Zhang Xiao, with its deceased founder Zhang Hongbao sitting in the sky.

In the Northern province of Heilongjiang, hundreds of police officers surround and arrest in the early morning citizens gathering in public parks for Qigong exercises supposed to prevent the COVID-19 infection. This is happening in ten different provinces, although Heilongjiang appears to be specifically targeted, and involves hundreds of specialized agents. They are fighting a xie jiao, a banned religious movement, known as Zhonggong. The only problem is that, according to earlier CCP sources, Zhonggong should no longer exist. It has been liquidated several years ago, and totally eradicated by 2016, one of the few “success stories” the specialized agents tell about their long-lasting fight against the xie jiao.

However, it appears that even this “success” was not definitive. To understand what happened, a short history of Zhonggong is needed. Zhang Hongbao (1954–2006) was born in Harbin, the capital of Heilongjiang, on January 5, 1954. While the organization he founded is labeled by the CCP as a xie jiao,and his theory “an anti-social, anti-scientific heretical system based on idealism and theism,” the part of the story the Party does not tell is that Zhang was himself a respected member of the CCP.

A high school teacher in Harbin, Zhang was sent by the Party in 1985 to Beijing to obtain a college degree. He did not complete his academic education, but attended the Chinese Qigong Further Education Academy and became an accomplished teacher of Qigong. This was before the Falun Gong incident of 1999, when Qigong was perceived with sympathy by the CCP. Since he was studying mechanical engineering, Zhang built a system of Qigong where an engineering jargon and theories of automation co-existed with ancient Chinese martial art, diet, and healing techniques. According to David Palmer, a scholar who had studied in depth the origins of the movement, he called it “Chinese Qigong for Nourishing Life and Increasing Intelligence” (Zhonghua yangsheng yizhi gong, 中华养生益智功), or, in short, Zhonggong (中功).

Just as it happened with Falun Gong in its early years, Zhonggong was not received with hostility by the CCP. On the contrary, starting in 1987, Zhang offered seminars inter alia at Beijing University, the China Academy of Sciences, the Central Party School of the CCP, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Justice, and the China Academy of Social Sciences. These events were favorably covered by the Party’s People’s Daily. According to Palmer, at least one minister and one deputy minister participated. A hagiographic biography of Zhang written by Ji Yi sold ten million copies. Zhang himself claimed that Zhonggong had 38 million followers.

Just as it happened to Falun Gong, Zhonggong was a victim of its own success, particularly of its success among high CCP cadres. The Party started perceiving Zhonggong as a potential rival. And when in 1999 Falun Gong organized a demonstration in the Zhongnanhai area in Beijing, where the CCP senior political leaders live, the incident not only sealed its fate but persuaded the Party that the time had come to liquidate all Qigong independent organizations. This, as scholar Ed Irons reported in an article in The Journal of CESNUR, also involved Zhonggong. While Zhang was well connected, and vowed to resist by hiring the best CCP lawyers, he understood that his days as a free man in China were numbered when he was told that some twenty women were ready to testify they had been raped or sexually molested by him (a frequent charge against xie jiao leaders in China). In December 1999, Zhonggong’s considerable assets were confiscated.

Zhang Xiao lectures in front of a portrait of Zhang Hongbao.

Zhang escaped via Guam in 2000 to the United States, where he failed to obtain full political asylum but was granted Protected Person Status in 2001. He became increasingly involved in militant anti-Communist activities, and even president of a Chinese government in exile, which led to quarrels and lawsuits with other Chinese dissidents living in the United States. Zhang died on July 31, 2006 at the age of 52, when his car collided with a large truck on the Arizona highway. His followers suspected foul play, and accusations of a Chinese conspiracy to kill Zhang were mostly relayed by the Falun Gong-connected Epoch Times.

After Zhang’s death, the authorities believed that the crackdown on Zhonggong initiated in 1999 had almost destroyed the movement, although some smaller branches remained. Great Buddha Qigong, founded by Zhang’s biographer Ji Yi in 1995 after he had left Zhonggong in 1994, was reduced to a small group. The authorities were more concerned with a branch called Maitreya Buddha Tao, founded in Shandong by Zhonggong leader Li Changlu, but by 2016 announced that it had been liquidated too, with its main leaders arrested and sentenced.

However, Zhang’s secretary, a woman called Zhang Xiao, born On October 4, 1966 in Longyan, in Fujian Province, kept Zhonggong alive overseas, and eventually moved the headquarters from the United States to Japan. Patiently, she reorganized a clandestine network in China, using several different names for the movement, including “Tianhua Culture,” “Oriental Health Cultivation Method,” and “Oriental Bigu Health Cultivation Method” (bigu is a Daoist diet and fasting technique, based on avoiding cereals).

With COVID-19, Zhang Xiao launched a set of anti-COVID Qigong exercises, which became quite successful. The CCP had discovered before that the network of her followers in China was far from being small. Originally believed to operate mostly through the Internet, in fact Zhang Xiao’s incarnation of Zhonggong has local centers in several provinces, the largest in Heilongjiang. According to the police, one was hidden in a massage parlor in Fuyuan, Heilongjiang. The city sits on the southern bank of the Amur river, and on the northern bank is Russia. Russian clients cross the border and liberally patronize the massage parlors in Fuyuan, but this one attracted the attention of the authorities because the masseuses were, unusually, old women. In fact, rather than massages, they were selling teachings on Zhonggong and artifacts blessed by Zhang Xiao.

Zhonggong material seized at the raided massage parlor in Fuyuan. Source: Xi’an Public Security Bureau.

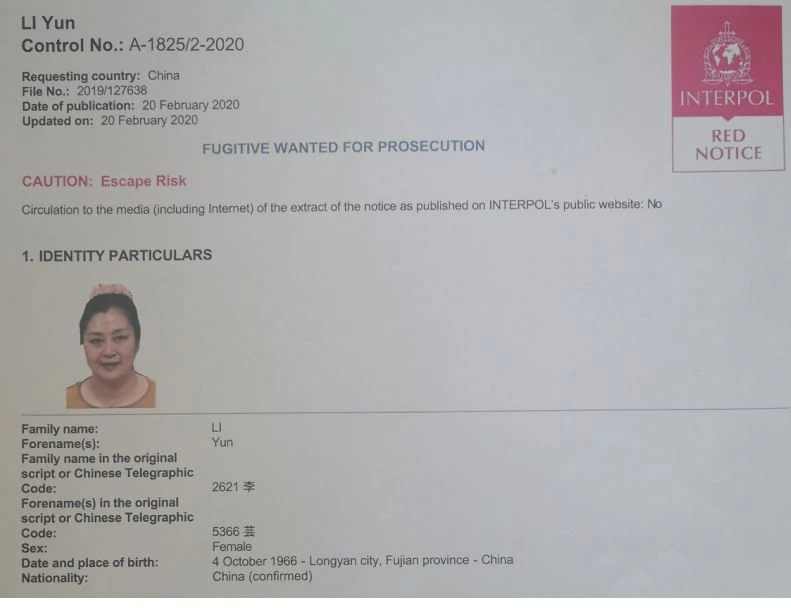

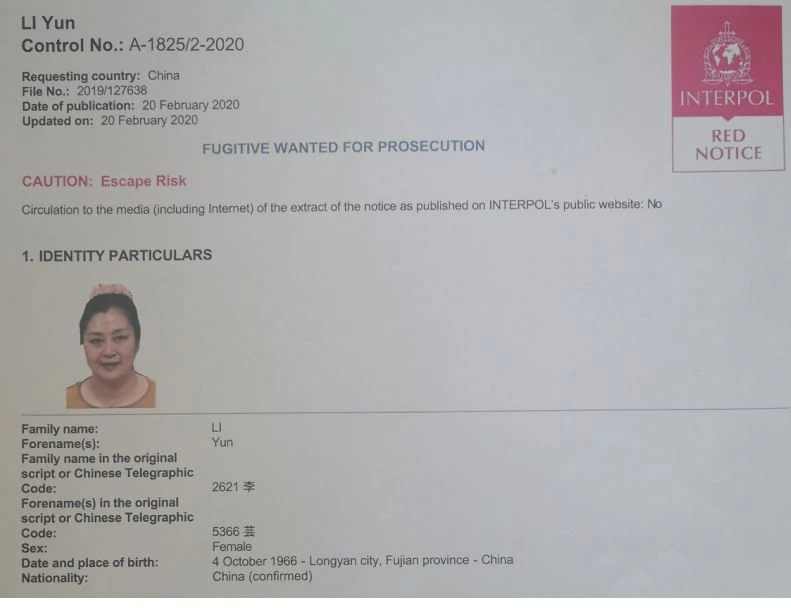

Massages or not, the CCP had to admit that Zhonggong had not been eradicated, and Zhang Xiao’s organization is alive and well in China. This year, China issued an Interpol Red Notice to arrest Zhang Xiao in Japan, and extradite her to China. Normally, these requests fail, but one never knows what kind of political and other pressures China may now exert.

Interpol Red Notice against Zhang Xiao, issued upon China’s request. Source: Xi’an Public Security Bureau

Massimo Introvigne

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote