The Coronavirus Outbreak Could Derail Xi Jinping’s Dreams of a Chinese Century

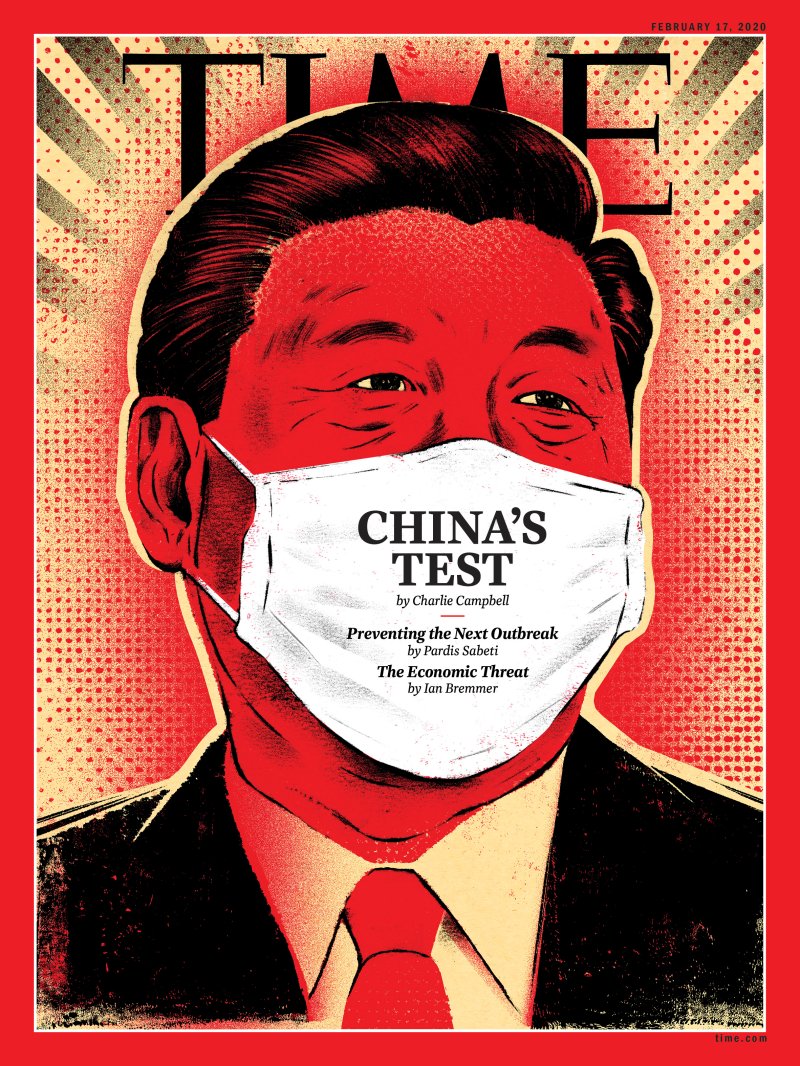

President Xi Jinping said on Feb. 5 that China is “confident and capable” of handling the coronavirus Paolo Tre—A3/CONTRASTO/Redux

BY CHARLIE CAMPBELL

6:18 AM EST

It took eight hours for a doctor to see Wu Chen’s mother after she arrived at the hospital. Eight days later, she was dead.

The doctor was “99% sure” she had contracted the mysterious pneumonia-like illness sweeping China’s central city of Wuhan, Wu says, but he didn’t have the testing kit to prove it. And despite the 64-year-old’s fever and perilously low oxygen levels, there was no bed for her. Wu tried two more hospitals over the next week, but all were overrun. By Jan. 25, her mother was slumped on the tile floor of an emergency room, gasping for air, drifting in and out of consciousness. “We didn’t want to see my mom die on the floor, so we took her home,” says Wu, 30. “She passed the next day.”

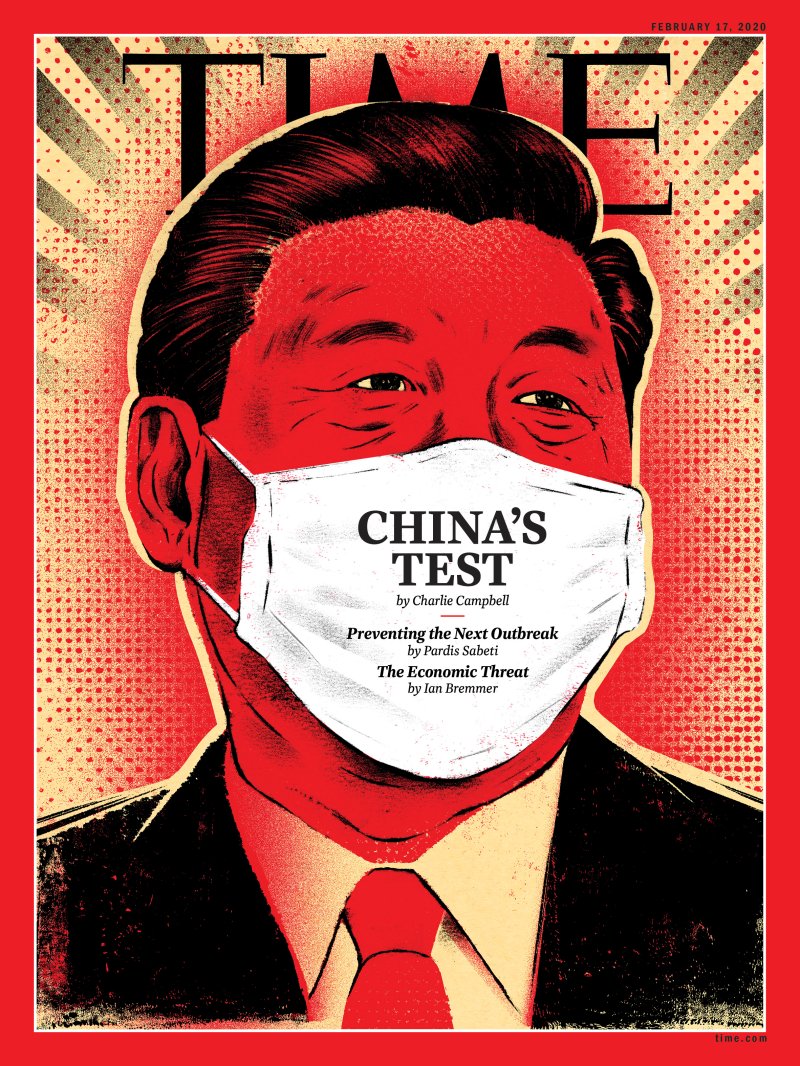

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez for TIME

Because she did not want a spell in jail for dissent to compound her grief, Wu asked TIME to refer to her by a pseudonym–a reasonable request and one that carries with it a measure of what each virus death means to the People’s Republic of China. The novel coronavirus known as 2019-nCoV threatens more than the 24,000 people known to be infected as of Feb. 4 or the 492 it has killed. It also looms over the national rejuvenation project of President Xi Jinping and the rigid, top-down rule being tested by all that the disease brings with it, including distrust in a population the government pledged to keep safe. Since China belatedly acknowledged the severity of the outbreak, every organ of the Chinese state has been harnessed to enforce an unprecedented quarantine on 50 million people across 15 cities. China’s government has unleashed a 1 billion yuan ($142 million) war chest to fight the outbreak amid a frenzy of construction work that, among other feats, erected a 1,000-bed hospital in just 10 days. That there was no cot for Wu’s mother may be understandable, given the time it took to comprehend the disease and how quickly it spread. But what to make of a government that cannot abide the grief of a daughter who took her ailing mother home rather than see her die on a hospital floor?

Transparency is essential to public health. But in China, doctors who reported the reality of the outbreak have been arrested for “spreading rumors.” Officials were pictured pocketing supplies meant for frontline medical staff, who were reduced to cutting up office supplies for makeshift surgical masks. Meanwhile, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has already started leveraging the crisis for propaganda by lionizing cadres leading containment efforts. “No crisis is too deadly that they can’t take a time-out to promote the party through manipulation of it,” says Scott W. Harold, an East Asia expert at the U.S. policy think tank Rand Corp.

In the fall of 2017, Xi took the podium at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to claim that China’s version of one-party autocracy offered an option for “countries that want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” Western democracy was messy and flawed, the argument went. In the years since that speech, China’s hubris has grown, nurtured by the tumultuous U.S. presidency of Donald Trump and the disintegration of the multilateral world order. But the coronavirus crisis threatens to rattle China’s authoritarian apparatus. “A major test of China’s system and capacity for governance” senior party chiefs called it on Feb. 3.

The 2019-nCoV outbreak is infecting some 2,000 people daily in China and has spread to at least 25 countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a “global health emergency.” And the fear is not limited to health. Global commerce now hinges on China’s $14.55 trillion economy, which in turn is governed by an opaque, authoritarian regime tightly coalesced around one man. Xi, burnished by a resurgent cult of personality, has amassed more power than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. He has leveraged Beijing’s economic clout to forward ambitions at home and abroad but also has struggled as no previous leader. “Since Xi came to power, problem after problem have occurred on his watch that he seems unable to effectively manage,” says Jude Blanchette, a China analyst at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies. These include popular unrest in semiautonomous Hong Kong, a disruptive trade war with the U.S. and now an unfolding health crisis.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote