‘You become an arse overnight’: the pitfalls of having a hit novelty single

We love them (for about five minutes). Then we hate them (for ever). But what do the people who made such classics as Kung Fu Fighting and the Crazy Frog think of them now?

Peter Robinson

The Guardian, Thursday 11 September 2014 13.38 EDT

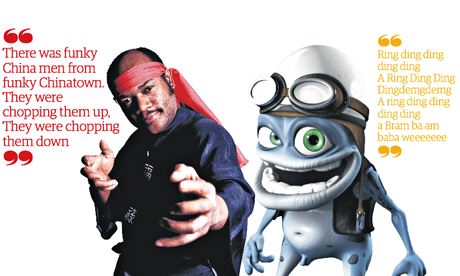

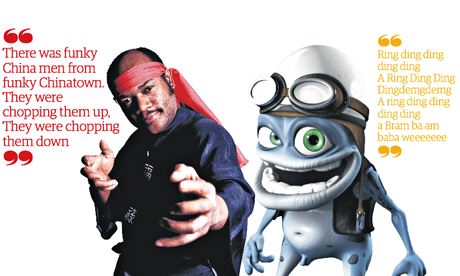

Carl Douglas of Kung Fu Fighting and the Crazy Frog … where are they now? Carl Douglas of Kung Fu Fighting and the Crazy Frog … where are they now? Photograph: Guardian

In 1974, a 32-year-old Jamaican singer called Carl Douglas was hoping to release a single called I Wanna Give You My Everything. One afternoon, his label’s head of A&R announced that the single could come out as soon as it had a B-side, and asked his colleagues to sift through Douglas’s recordings for suitable candidates. He went to lunch, came back an hour later and was greeted by a defiantly absurd disco banger by the name of Kung Fu Fighting.

That executive’s response, Douglas explains today from his Hamburg home, was this: “JESUS CHRIST! This is a monster. We need a B-side for THIS. He’s going into the FUTURE!”

Carl laughs at the memory. That’s only fair: Kung Fu Fighting was released 40 years ago this month, sold 11m copies, won a Grammy, and hit No 1 on both sides of the Atlantic. Last year, the song topped the charts in China for the first time, and is one of the 50 best-selling singles of all time. It’s also the quintessential novelty single.

In 2014 novelty records continue to seduce record buyers around the world. Forty years (and one week) after Kung Fu Fighting topped the UK charts, Meghan Trainor’s quirky, doo-wop-inspired rotundity anthem All About That Bass will be released in the UK having already hit No 1 in 28 countries. Like Kung Fu Fighting and a surprising number of novelty records it is exquisitely written and produced. But just like Kung Fu Fighting and era-spanning hits from Yakety Yak and Yes! We Have No Bananas to One Pound Fish and Can We Fix It? it is, at its heart, a novelty track.

Rarely championed by media gatekeepers, novelty hits prompt a visceral, unmediated type of connection with record buyers – one that’s arguably stronger than you will find in pop’s better regarded sub-genres. But they have morphed over the decades. In pop’s early days, when audiences would come to know songs such as David Seville’s 50s hit The Witch Doctor, Napoleon XIV’s 1966 hit, They’re Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa! (whose B-side was simply the A-side played backwards) primarily through radio broadcasts, novelty hits were frequently song-driven efforts.

By the 80s novelty hits such as seemed to come with a far greater reliance on presentation and personality – a novelty single came part and parcel with a career in light entertainment. In 2014, a track like All About That Bass has blown up – like Gangnam Style – through YouTube, where its brilliantly charismatic video is the embellishment on the song’s eccentric sonic styling.

It is a curious and perhaps heartening fact that very few novelty hits are totally worthless on a musical level. “Novelty records usually tread the knife-edge of taste,” admits producer Nick Coler, who worked on the Timelords single in 1988, and later propelled the Tweenies into the top 5. “So they’re normally considered crap, but all the biggest novelty records are generally well recorded.”

It’s certainly easy to reassess the Simpsons’ Do the Bartman when you know Michael Jackson wrote it. Equally, does William Orbit’s role in Loadsamoney (Doin’ Up the House) qualify that song for honorary Balearic classic status? More recently, does the presence of Stargate – the team behind hits for Beyoncé, Rihanna and countless others – on Ylvis’ The Fox (What Does the Fox Say?) make that song seem any less inane? Either way, Coler suggests that novelty records must tick one further box. “They normally have someone behind them who’s taking the ****,” he says, “but in a pleasant manner.”

All pop transports the listener to the point in time when they listened to it, but novelty records – obsessed as they often are with zeitgeist – can prove particularly potent portals to specific moments. The Cuban Boys’ 1999 hit Cognoscenti vs Intelligentsia was based on the hugely popular “hamster dance” song that itself proved an early viral sensation as dialup connections gave more and more families internet access, and says as much about that era as the Chainsmokers’ recent viral hit #Selfie does about 2014.

“I had this idea of a concept album chronologically sampling music from the 20th century,” remembers Cuban Boys founder John Matthews. “It would end, I decided, with the millennial No 1 – an ultra-banal, ultra-repetitive, internet-flavoured hit.” The album never materialised but Matthews did create that internet-flavoured hit – based on the hamster dance song – and found an unlikely champion in John Peel. The Cuban Boys signed to EMI, and the single made the top five.

A couple of years later Matthews teamed up with jocular rapper Daz Sampson, who’d already charted with his own version of Kung Fu Fighting, to form Rikki & Daz. They roped in Glen Campbell – “I think the extent of our UK credibility may have been slightly exaggerated to his people,” Matthews laughs – for a version of Rhinestone Cowboy. Later, they reinvented themselves as the papier mache-bonced Barndance Boys. “We hyped that Barndance Boys single to No 1 on [TV music channel] The Box by phoning up a million times,” Matthews admits. “When thousands of copies were ordered in the shops it inevitably turned out nobody wanted them, and we may have helped bankrupt Woolworths. Maybe we were dancing in the last flames of the old-school novelty hit back then, but we were still desperately trying to keep that career fire burning.”

Technology, with its endless distractions and resulting drop in shared experience, has not been kind to the brand of novelty record many cherish, or at least fail to forget. “You need the focus of a nation for a gimmicky song,” Matthews explains. “As people are so rarely looking in the same direction now I think the ability of a mass audience to recognise and enjoy novelty music has been lost.”

In the modern age, with most releases strategised to within an inch of their lives, it is cheering that novelty hits can still happen almost by accident. In 2012 Sam & the Womp, the sort of fringy act you might find pootling away in the outer reaches of the Glastonbury site, had a surprise No 1 with an absurd drum’n’bass-inspired song called Bom Bom. Radio 1, apparently on something of a whim, awarded it heavy rotation. Sam & the Womp signed to Warner Brothers Records.

“In our mind Bom Bom really wasn’t a novelty song,” admits the band’s Sam Ritchie (in pleasing Seven Degrees Of Kung Fu Fighting Separation, he’s best friends with the godson of one of Kung Fu Fighting’s co-writers). “Our original instrumental worked well, but the slightly noveltyish lyrics did bring it to life. Only in hindsight am I now seeing that it had real novelty value.”

When it came to the second single, lightning refused to strike twice. “We thought there’d be a play on Fearne Cotton’s show,” Sam remembers. “It didn’t happen, and that was it.”

Instant, widespread recognition is important in a novelty hit, but it doesn’t always pan out well. Today, Alida Swart works in the operations department at a London telecoms company, but between 1996 and 1998 she and three friends were in a girlband called Vanilla. At an early stage in Vanilla’s career their manager explained that he had bought the rights to a piece of music, which producers would then write a song over. The piece of music was Mah Nà Mah Nà, a song closely associated with the Muppets; Vanilla’s resulting 1997 single, No Way No Way, was named the 26th worst song ever by Channel 4, but was inescapable at the time.

Swart laughs off the longstanding rumour that Vanilla signed to EMI as the result of someone losing a bet, but accepts that Vanilla were launched with what was unmistakably a novelty single. “When we first heard it we just laughed,” she remembers. “Then we looked at each other. Two of us wanted to be doing R&B. But we thought: ‘We might as well do it.’” Girl Power was at its peak; they reasoned that Wannabe had itself been gimmicky. No Way No Way got to No 14 but Vanilla’s second single only managed No 36 and the band were dropped. Nonetheless, Alida looks back fondly. “People still tell me today that they remember this song,” she laughs. “It’s been nominated as the worst song of the 90s quite a few times, but at least it’s remembered.”

Decent careers have been built on less. In 1997 Steps were signed for just one single – the line-dancing cash-in atrocity 5, 6, 7, 8 – but when it sold 300,000 copies they were given another single and the rest is history, or Tragedy: they eventually sold 20m records. A few years earlier, Right Said Fred got their foot in the door in a similar way.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote