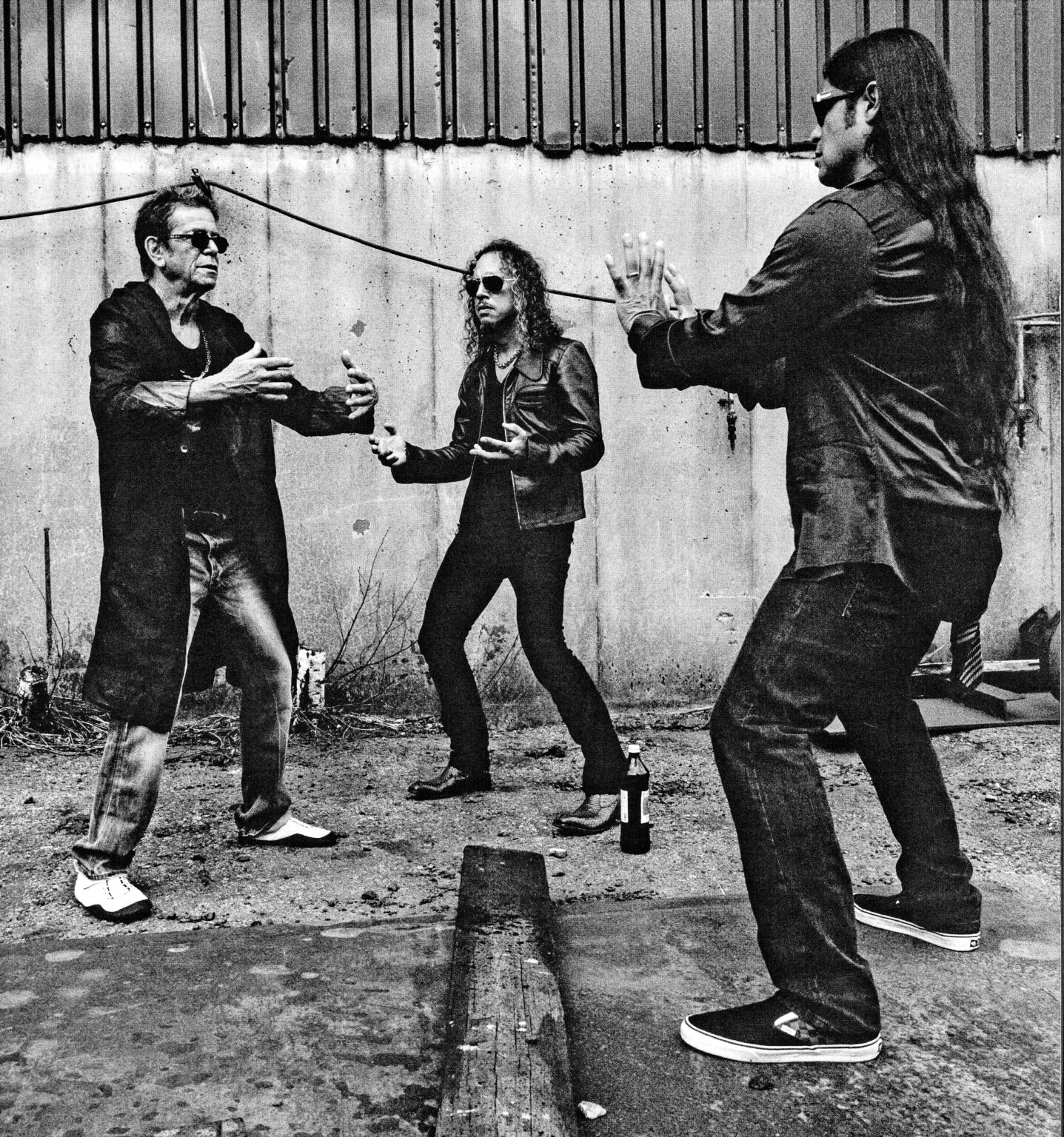

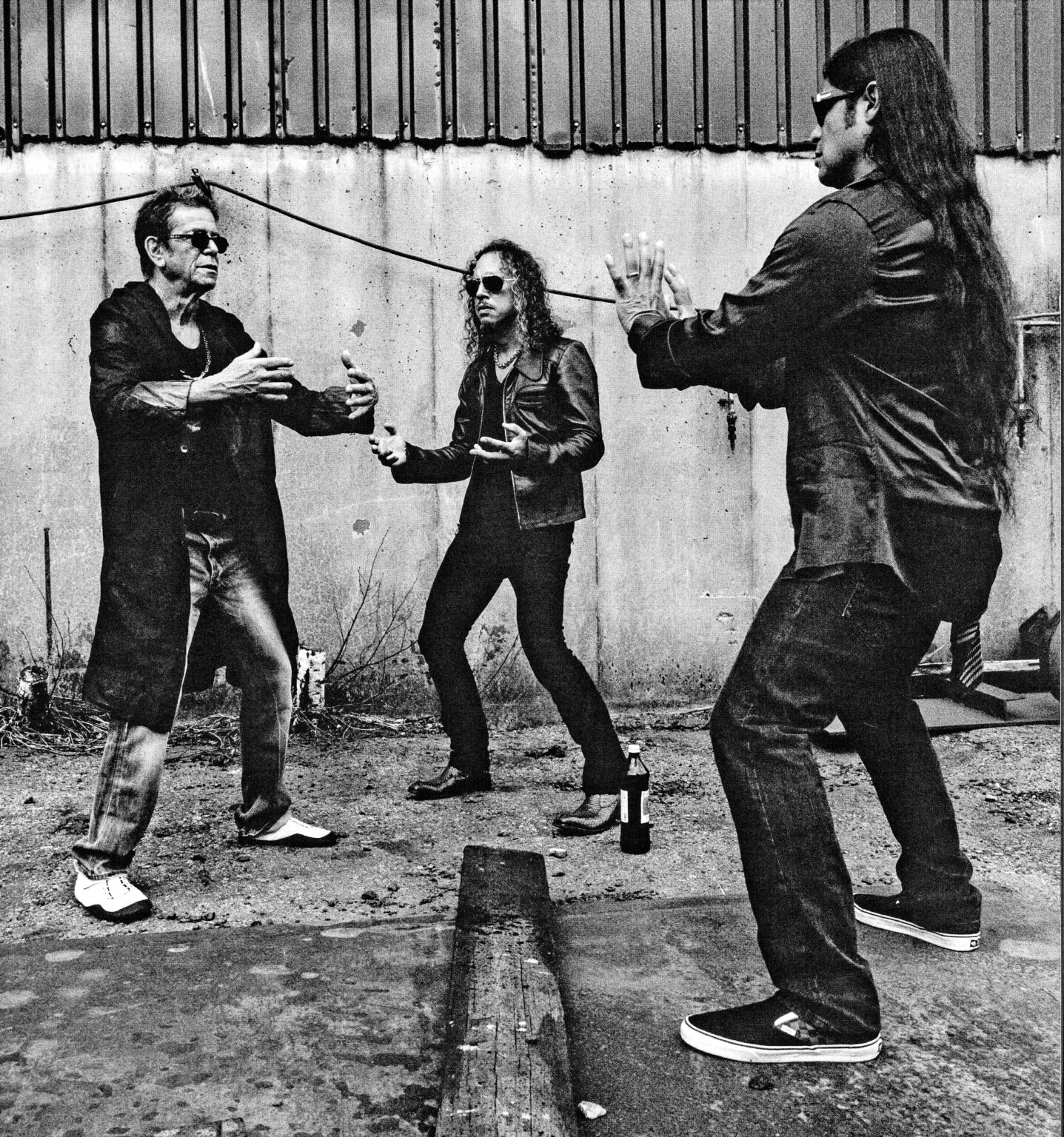

Lou Reed practicing Tai Chi with Metallica, by Anton Corbijn

ANDERSON: Oh, nice. Tell me just a little bit—I know people who are reading the book get a certain picture of you and Lou, but can you just tell me a little short story about how you met Lou and what he meant to you at the beginning? Before you got to know him that much?

ULRICH: Yeah, the first time, Jann Wenner and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame crew threw a—I believe it was the 25th anniversary celebration of the Hall of Fame in, what are we talking, was it ’09?

ANDERSON: Yeah. I think it was ’09.

ULRICH: Yeah. At Madison Square Garden. And so the idea that they came up with was that three or four artists would host a segment, and I believe U2 hosted a segment, I think Springsteen hosted a segment. And then we were asked to host a segment representing harder rock. So we started coming up with artists that would fit into our world. We picked Dave Davies [from The Kinks], Ozzy [Osbourne], and Lou.

ANDERSON: Oh what a crew!

ULRICH: Listen, first of all, we—Metallica—were wondering if they had sent the invitation to the wrong people, or wondering how we ever ended up in that esteemed and respectful company. But obviously we were super-psyched and just looking at it as an incredible opportunity to connect with so many people that we respected and had idolized and who had inspired us for decades. So we were down at, I can’t remember—it was a rehearsal studio somewhere in Manhattan, and I can’t remember what order we did. But all three of them came in and when Lou came in, there were a lot of amplifiers and a lot of speakers and a lot of gear. And he came in, and things were terribly loud, and there was just a lot of stuff everywhere. I remember he just started like, “Why is all this gear here?” and would just instantly challenge everybody, which was great, because nobody ever questioned anything that was going on. He was like, ‘What are we doing here? Why is it so loud?’ And then as we started talking and trying to figure out exactly what material we were going to hone in on, somebody—I can’t remember who—said the word medley…

ANDERSON: Oh, god. Medley.

ULRICH: Yeah, exactly! Lou said, “I don’t do medleys.”

ANDERSON: I’m sure.

ULRICH: It went south from there and continued going south. I think he actually walked out, and I took it upon myself to go find him, and connect with him. He and I had a one-on-one for, I don’t know, maybe it was 10, 20 minutes, and we connected in a very nice way, and I encouraged him to ride it out, and to understand that however this was going to play out, that we would make it work for everybody, medleys or not. And as you know, more than anybody, within a short amount of time, it was a 180 and it was the beginning of a love affair and this incredible relationship. A few days later, we ended up playing this incredible set in front of Madison Square Garden and the world, and as we were parting that night, down in the bowels of Madison Square Garden, in like, underground level 23, as we were all going in a separate directions, Lou said, “Let’s work together one day on something in the studio, maybe make a record or something.”

ANDERSON: I remember that so well. I was there and I remember how excited he was. He was really like an eight-year-old boy. He was like, “Oh my god, these guys are so amazing.” That was the biggest thrill for him, yelling out to you like that.

ULRICH: Yeah, I’ll take that one with me forever. It was priceless.

ANDERSON: Tell me a little bit about Lulu, because that, for me, was one of the most intense parts of my life with Lou, when he was working on that record with you, and digging this stuff from way down at the bottom of his heart, things about his father, things about men and women and love and hate and spite… That record scared me. I just remember a conversation that I had with David Bowie and he said, ‘Make no mistake, this, in 25 years, will be considered Lou’s best work. This is so dangerous. And that’s who he is. People just don’t ever understand him, and they don’t get that they don’t understand him. They don’t get that he’s ahead of his time.’ I was really struck by that.

Training with a spear at home on the roof, photographed by Ren GuangYi

ULRICH: Sometimes it’s also easier to not understand it because it may require more work to try to actually envelop yourself in it.

ANDERSON: A lot of work. And painful work. It’s not fun stuff. If you are really listening on many levels, you could hear it as this incredible sound force field coming at you. But on another level, when you listen to “Junior Dad,” for example… Woah.

ULRICH: It’s incredibly powerful, and it’s incredibly naked. All the emotions are literally right there. There’s nothing—no filters, no masks, nothing that’s separating the artist or the sound of what’s coming out for the listener. You’ve got to proceed with a lot of caution.

ANDERSON: Yeah.

ULRICH: I don’t think we had really understood the intensity of the work and the scale of it, until probably somewhere towards the end of finishing it, when Lou and James [Hetfield, Metallica’s lead vocalist] and I started our coast to coast conversations about jumping into this project. James and I, and the rest of the band, were trying to figure out our role in it, to try to serve Lou, but also to bring to life what the musical bedrock could be to everything that was coming out on top of it. It was instinctive in the beginning. And for us, it was those kinds of impulsive and momentary musical reactions were not something that we had ever really done before, because with our own records and with our own process, it’s quite labor-intensive. And we do a lot of analyzing, we remove ourselves from the creative process to try to get some space, and an understanding of what it is we’re doing. But everything with Lou was about the moment, and that was something we weren’t prepared for, but when it happened —

ANDERSON: You recognized it.

ULRICH: It was so ****ing liberating. It took a day or two, as we were going through those moments, and we were trying to come up with something that would work for Lou and for the scale of the project. And as we were working our way through the ideas and feeling them out, Lou said, ‘That’s great.’ The first couple of times it was like, ‘Well, thank you for that, let’s now go out and make it happen.’ But he would say, ‘No, no, no, that was great.’ As in, that was it.

ANDERSON: I know. He was a one-take guy.

ULRICH: The first couple of times it happened, it was just like, ‘What?’

ANDERSON: It’s shocking.

ULRICH: We were so unprepared for that and didn’t quite know how to react. And obviously, since we had not worked together before, we knew that part of the attraction was the unpredictability. But we didn’t know what that meant, Like, ‘Are we good for today, but then we’ll come back tomorrow and try again?’

ANDERSON: Nope. Not Lou. That’s it. We’re done.

ULRICH: Yeah. We definitely had to feel our way through it as the days went on. But again, circling back to the trust element that I mentioned, as soon as that trust was there, and as soon as we knew that we were all going to be safe, there’s a freedom that comes with that, and you just liberate yourself from all the **** that weighs you down. That was when we really just went into overdrive at a completely different level, and all this music and noise, and all these waves of craziness came out. Then Lou put these incredible words, and poetic thoughts, and lyrics, or however you want to characterize it, on top of it. The work was given birth to in two, or maybe three weeks of recording.

ANDERSON: Yeah, I remember how fast it was. But he’s a one take guy, and a lot of times, it’s strange to go with it. To have the trust in your intuition like that. I had a feeling that you guys really did it that way, because it felt really intuitive.

ULRICH: Yeah. It’s something that wasn’t in our arsenal until then, but we embraced it quickly. And like I said, there was an incredible—and I know this word is overused so much—but there really was just a freedom to it. Liberating is maybe a better word, because we just set ourselves free and trusted in the moment. There was no reason to go back to continuously readdress what had just happened.

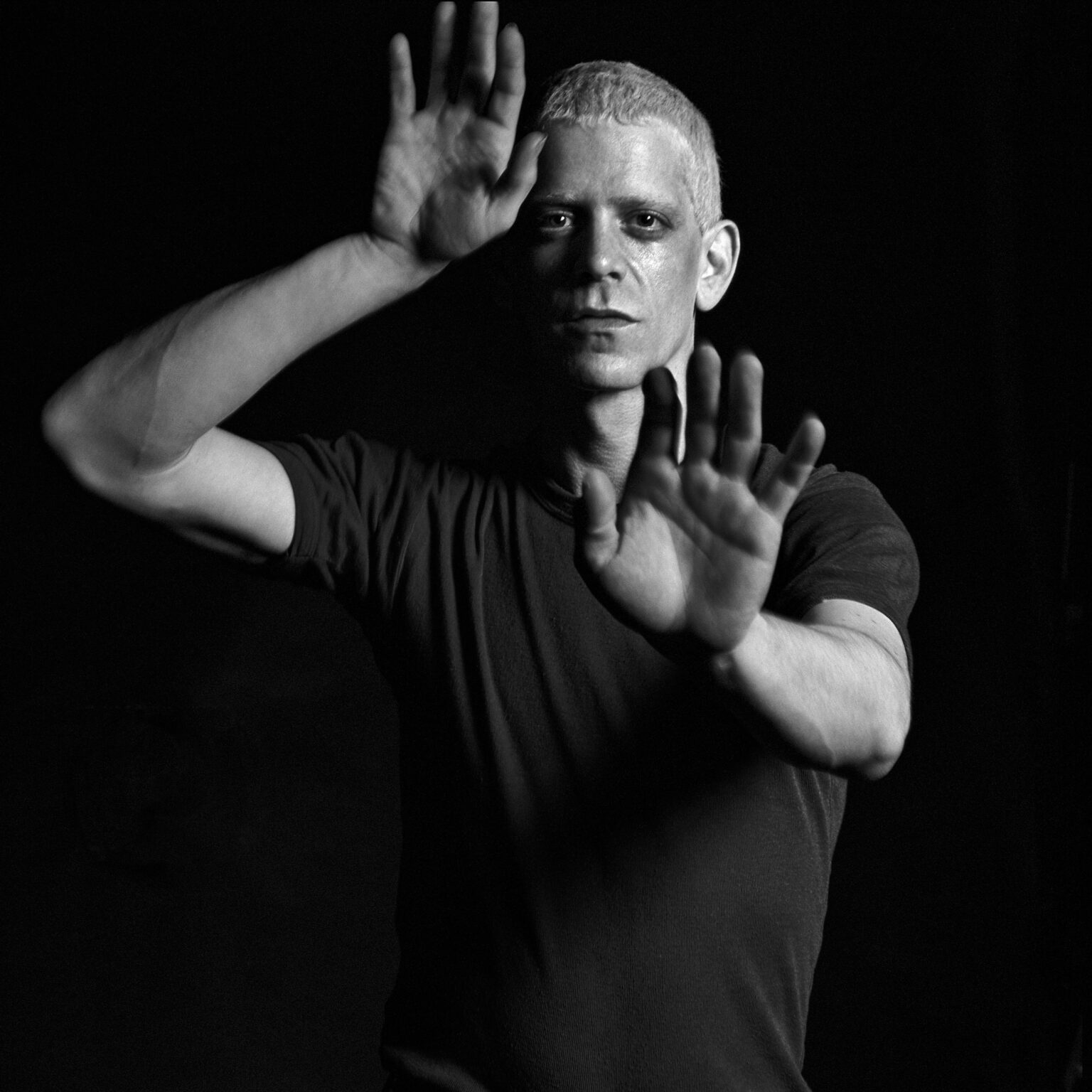

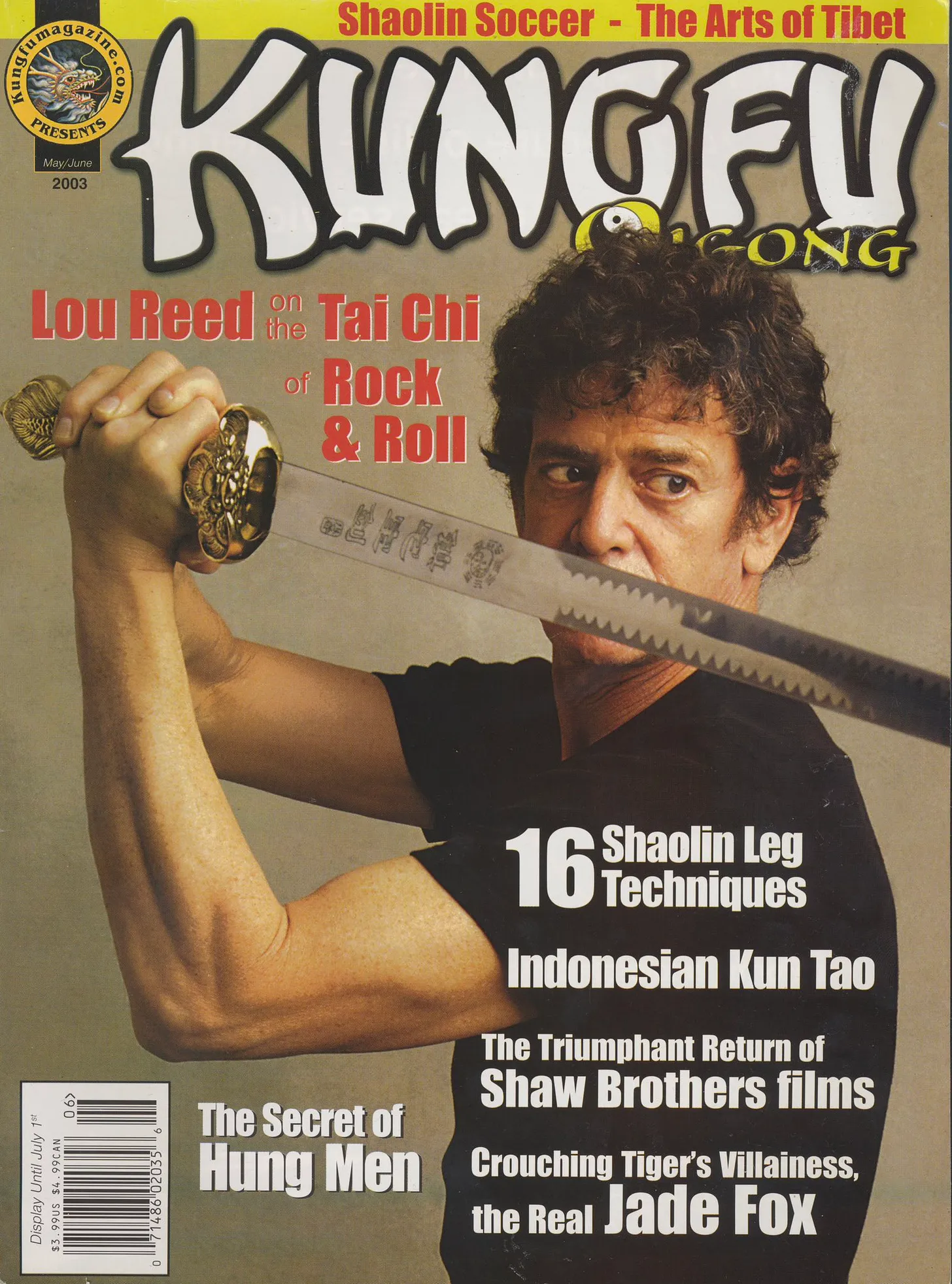

ANDERSON: Yeah, that’s the way he lived. He wasn’t rehashing the past and he wasn’t trying to perfect it ever. It was just really rough and so honest. There’s a picture in the book of you, and it looks like you’re doing Tai Chi. Did he teach you some standing mountain moves or did he try to?

ULRICH: No, I learned from Kirk [Hammett, lead guitarist of Metallica], and Rob [Trujillo, Metallica’s bassist], but especially Kirk. He connected with Lou on that a lot.

ANDERSON: Maybe I’m making this up, but I see Tai Chi moves in your playing. Just these incredible moves you do… That’s Tai Chi. That’s power. Lou loved that about you so much—what you put physically into your playing.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote