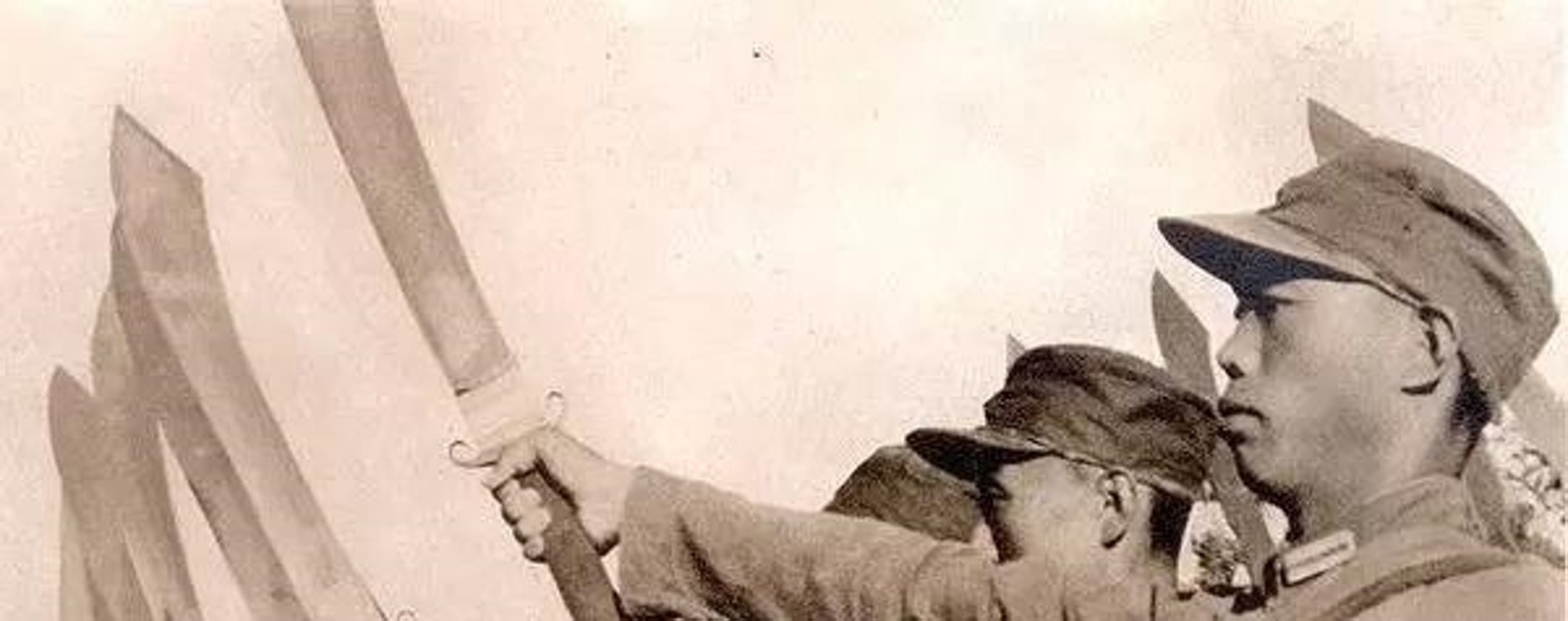

Jukendo martial art players participate in a national championship held at Tokyo's Nippon Budokan in August 2014. The sport, mostly practiced by Self-Defense Forces personnel, will be included on the list of martial arts that can be taught at junior high schools. | ALL JAPAN JUKENDO FEDERATION

REFERENCE | FYI

A jukendo comeback?

Prewar bayonetting martial art makes return to schools

BY MIZUHO AOKI STAFF WRITER APR 24, 2017

A little-known Japanese martial art called jukendo came under the spotlight recently after it was stipulated in the revised junior high school curriculum guidelines for the first time as one of nine martial arts schools can choose to teach students.

Due to its historical background as combat techniques developed and used by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II, the decision has sparked criticism among many, with some branding the move as anachronistic.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Cabinet denied such accusations in a statement on April 14, saying it was not the revival of militarism or a move to return to prewar values. Jukendo was stipulated because “it was considered to further improve the flexibility of budo’s contents,” the statement said.

What is Jukendo?

Jukendo, which literally means “a way of the bayonet,” is a Japanese martial art similar to kendo.

Donning robes and armor for protection, practitioners jab each other’s throats or bodies using wooden mock rifles, according to the All Japan Jukendo Federation.

It is officially listed as one of nine Japanese martial arts by the Japanese Budo Association. It is mainly practiced by Self-Defense Forces personnel.

Why is it controversial?

Many associate the martial art with the Imperial Japanese Army.

According to the jukendo federation, its history can be traced back to the Meiji Era (1868-1912) when the Imperial army developed a combat style using rifle-fixed bayonets by incorporating traditional spear fighting and French bayonet techniques.

“Back then, it was the techniques for fighting,” said jukendo federation vice president Takeshi Suzuki.

But following Japan’s surrender in 1945, it was banned along with other martial arts by the Allied Occupation Forces.

After the ban was lifted in the 1950s, it was developed as a modern sport with completely different purposes, including honing etiquette and training minds and bodies, Suzuki said.

How popular is jukendo in Japan?

Around 30,000 people are currently registered as members of the sport, out of which roughly 90 percent are SDF personnel, according to the federation.

The number of participants is much smaller than major martial arts such as judo, which has around 160,000 practitioners, and Kendo, which is practiced by about 1.8 million people in Japan.

The federation said it had around 50,000 members a decade ago, but the number has since dwindled due to the nation’s shrinking population and people’s declining interest in martial arts in general.

Apart from the 30,000 members, the federation also has 1,000 junior members who are junior high school students or younger.

Suzuki said it has five non-Japanese members, from France, Australia, New Zealand and Poland.

Would jukendo be a compulsory subject at junior high schools under the new curriculum guidelines?

No. Since 2012, budo has been a mandatory subject for first- and second-year junior high school students. But it is up to each school to decide which martial arts to teach.

Although the current curriculum guidelines recommend sumo, kendo and judo, junior high schools have the freedom to teach other Japanese martial arts that are not listed, including jukendo, according the education ministry.

In reality, however, only one junior high school in Japan, in Kanagawa Prefecture, teaches jukendo, the ministry said.

As some teachers hesitate to teach subjects that are not clearly spelled out in the guidelines, the jukendo federation believes it will become easier to promote the martial art to junior high school teachers once the new guidelines take effect in fiscal 2021.

Why did the government include jukendo in the new guidelines?

Jukendo was initially not listed in the draft version of the guidelines released by the education ministry in February, even though all other martial arts recognized by the Japanese Budo Association were stipulated.

An official at the sports agency, an external bureau of the ministry, said it was excluded because it was hardly taught in junior high schools.

But the ministry’s draft guidelines sparked anger from jukendo enthusiasts, including Masahisa Sato, an Upper House lawmaker from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

Sato, a former GSDF commander, urged the ministry to stipulate jukendo in the guidelines during an Upper House foreign affairs and defense committee session in March.

He also called on fellow LDP members, former SDF personnel and his supporters to send public comments to the education ministry, according to his blog.

The sports agency official said the ministry decided to include jukendo in the guidelines after receiving “several hundred” public comments urging its inclusion.

While the ministry’s move was welcomed by Sato and other jukendo supporters, some slammed the decision, including Niigata Gov. Ryuichi Yoneyama.

Following the release of the new curriculum guidelines on March 31, Yoneyama tweeted that he was terrified.

Jukendo is different from kendo, judo and sumo, which are established as sports and practiced by many people, he said. “(The decision) is nothing but anachronistic,” he tweeted.

Will it be dangerous for children to practice the jabbing techniques?

Students will not be taught techniques to target opponents’ throats, according to the federation, which helped draw up teaching guidelines for jukendo.

First- and second-year students will only be practicing noncontact kata — the basic movements of jukendo, Suzuki said.

The students may take part in a match in the final year — but only if they fully master the basics and wear formal protective gear, he added.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

It's funny how modal we are.

It's funny how modal we are.