I find myself turning to these stories to guide and console myself as we all await a climate catastrophe.

In 2016, the renowned Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh, in a book entitled The Great Derangement, described the collective failure of “serious” literary fiction to grapple with climate catastrophe. Ghosh called for writers and artists to engage with apocalyptic thinking that might be able to delay climate catastrophe by spurring the global culture into action. Ghosh laments that, for the most part, these conversations were relegated to genre writing. The only part of his account that I contest is his dismissal of genre writing as unimportant or unserious. I make no highbrow claims as to what I read in an attempt to forestall the inevitable or seek out consolation; I read kung-fu stories, and Louis Cha’s in particular. This isn’t just a guilty pleasure; it’s an intentional alignment with a certain kind of underground resistance, a riptide wilding the tranquil surface of institutional prose.

When Mao Zedong rose to power in the 1940s, he developed and enforced a blueprint for a national Chinese literature that featured idealized heroes and formulaic plots. Louis Cha’s stories defy those formulas. The martial arts literary historian John Christopher Hamm describes Cha’s novels as “strategies for responding to the altered world.” Of course, Hamm is referring not to a world altered by climate catastrophe, but rather to one altered by the ascension of the Chinese Communist Party. I’ve discovered that much of his approach is transferable to our 21st-century problems. In his book Paper Swordsman, Hamm points out that because mid-20th-century martial arts fiction did not “hew to overarching ideological dicta” or “serve the immediate needs of particular political campaigns,” it was “relegated to the category of ‘poisonous weeds,’ banned from the gardens of culture.” The way Hamm phrases this judgment makes the reader yearn to be a poisonous weed, to read and champion the minor genres. Where Ghosh grieved the lack of serious works of fiction grappling with the newly altered world, Hamm makes the case that it is the marginalized literary genres that are best suited for exploring the plight of humanity in such newly altered worlds.

Ghosh is far from the first literary scholar to tell us that the stories we tell ourselves about nature are broken. Back in 1999, American author William Kittredge published a collection titled Taking Care: Thoughts on Storytelling and Belief. In that book, Kittredge mourns what he calls “narrative dysfunction,” describing the ways in which the stories we tell ourselves about nature, both individually and collectively, are broken. In the absence of stories that bind us to nature, holding us accountable to nature and to each other, Kittredge argues, we hasten nature’s destruction and our own.

But when I read Louis Cha, I feel as if the stories that connect me to my family’s past and to the earth remain alive. “The wind hard-hearted, the moon cruel,” a beautiful but suffering woman sings in the opening pages of The Past Unearthed. These words were penned by the lyrical Song Dynasty historian Ouyang Xiu; Cha’s novel begins by yoking one character’s personal suffering to collective cultural grief. As I read, I imagine my father as a child in a brand-new country, the tatters of one installment of these stories clutched tightly in his fist. I imagine stories as sinuous and armored as a dragon’s flank, and I remember the editor’s introduction to Cha’s first novel, the description of it as “a living dragon appearing in the flesh.” That phrase is a reference to the myth of Zhang Sengyou, who painted realistic dragons but didn’t paint their eyes in order to deny them the realism that would bring them to life. “The living dragon appearing in the flesh” refers to what happens next in the story: Someone paints the eyes onto the dragons, and they come alive — not as a marginalized genre, but as the embodied force of counterculture storytelling.

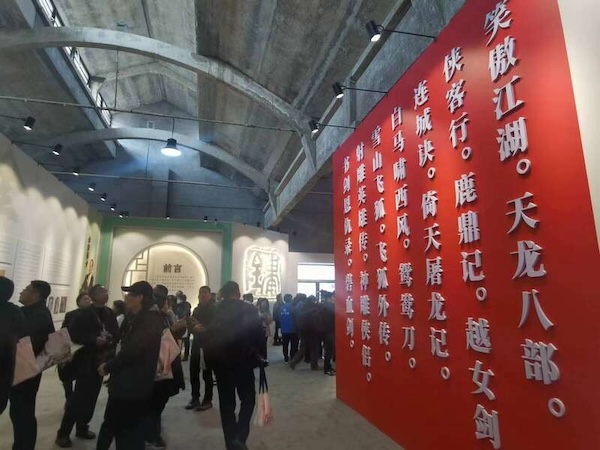

Louis Cha’s novels are popular in China, occupying a privileged place in the Chinese imagination that is perhaps similar to the position occupied by the Lord of the Rings trilogy in the English-speaking world. Globally, over 300 million copies of The Legends of the Condor Heroes have been sold, and, in recent years, Cha’s popularity in the United States has surged as well. I’ve chanced upon Cha’s books on other people’s shelves, and my personal consolation is beginning to feel collective.

Sally Deng/High Country News

I THINK I’ve come to understand something about the environmental narrative dysfunction that William Kittredge pointed out over 20 years ago. Kittredge and Ghosh both seem to believe that the stories that sustain us emerge out of some sort of elevated literary imagination. They fail to see the tendrils of popular, subversive, “low-brow” stories blooming all around them like weeds, like the good kind of poisonous weeds.

The tomatoes and peppers my father grows are unruly; they pour out of their garden beds and onto the driveway and porch. They’re members of the belladona family, which is full of poisons. Last night was the first hard frost, and my father didn’t bring the harvest in before it hit. Instead, perhaps deliberately, he left tomatoes and hot peppers on the stem, eggplants purpling the shadows, in defiance of the forecast. He was not thinking about waste, or plant cells rupturing from frost, or about running out of time. From what I can gather, he was imagining that maybe, against the odds, the forecast was wrong. Maybe the plants would magically survive, continuing to ripen.

In the absence of stories that bind us to nature, holding us accountable to nature and to each other, we hasten nature’s destruction and our own.

As he explains his reasoning, something in his tone reminds me that he escaped from Communist China, whisked across the grasslands in a basket, and that he survived the hardships of Taiwan, even after his family separated from the Nationalist forces; he survived the solitude of the blood oath his father made him swear — to never contact his cousins, whose parents stayed and fought for Communist China — my father, who lost four of his six younger siblings to untimely deaths. I wonder what the climate crisis feels like from the vantage of an immigrant who has somehow steered himself through what surely felt like the end of the world. Can the kung-fu legends that sustained him through that altered world sustain me and my generation through the age of climate collapse?

As I ponder, here I am, the gleaner, picking through the destruction of my parents’ garden. My dad searches for the ripest tomatoes abandoned on the vine, thinking he’ll use them in a stir-fry. I’m gathering the green ones by the fistful with no particular recipe in mind. It’s just that I can’t bear to see them go to waste, these stories not done with their telling.

Jenny Liou is an English professor at Pierce College and a retired professional cage fighter who lives and writes in Covington, Washington. Her debut poetry collection, Muscle Memory, was published by Kaya Press in 2022.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote