|

| A high-quality combat jian might have two attachments from blade to handle, one in the center of the hilt going through the middle of the tang and the second a pommel nut screwed on the end of the tang. |

Much information has been shared over the years regarding form and function of the Tai Chi sword or jian in Mandarin. However, defining and developing a strong and firm grip on the weapon is really the foundation for good sword play. Each different school of Kung Fu has their own specifics on gripping their particular jian. Most commonly it is the weight, style and design of the jian including its direct application that will determine the specific type of hand and finger configuration you will use to grip the sword (i.e., where to grab the handle, how the fingers should be placed, angle, direction and intent, etc.).

Sword Nomenclature

Before we explore the specifics of sword grip we must first understand each part of the sword as it applies to the jian in a simple breakdown.

Blade: the double-edged tapered blade is divided into four sections. The tang is at the base of the blade and is usually substantially thinner and shorter. This is the piece that the handle affixes on to. Most teachers agree the first third of the blade starting from the point down is where the blade holds the sharpest "double" cutting edge. This section is used strictly for cutting and stabbing. The middle third section is usually moderately sharp. It can be used for chopping or slicing cuts and blocking as it is thicker than the first third. The last third closest to the tang typically has dulled edges as cutting is not performed from this part of the blade.

Guard: a piece of metal with fittings made to secure the handle and protect the user's hand. In the case of the jian, it can be diamond-shaped with rounded edges. However the most common are: triangular slanting outward and away from your hand, diagonally, or triangular slanting inward towards your hand. These are the three main configurations. Some historians attribute the different designs to specific periods in Chinese history. What Tai Chi practitioners need to do is weigh the pros and cons of the "slanting up" and "slanting down" guard, then - based on those characteristics - decide which is best for you rather than just buying any sword that "looks good."

Tang: as mentioned above, the end-spine of the blade that a handle is fastened around or to. The tang is usually much thinner in diameter than the blade.

Pommel: a chunk of metal secured (often screwed) to the end of the tang. So the handle is between the pommel and the guard. A "tassel" is sometimes attached to the pommel. Some schools employ a functional use of the tassel, others do not. The pommel itself can be used as a blunt impact weapon.

Depending on the sword design, quality and price, the handle will be secured with varying levels of strength. Cheap, practice or ornamental swords often have very thin and short tangs with weak guards and low-grade handle materials. These weapons needless to say should never be used for contact sword sparring as a hard impact can loosen or dislodge the various hardware components. The tang can break, and handle detachments have been known to occur when practitioners are wielding substandard weapons during high-speed demonstrations. They are left holding the handle while the blade goes flying away. Well-made swords will feature a "full tang" design where the entire handle is bolted into the tang with metal rivets as opposed to only half or two thirds the length. This type of attachment is the optimum configuration as both the full tang and pommel share the load of the blade, making for a very secure grip.

Most modern jian handles are secured only by the pommel screw where it shoulders the entire load. The handle is just "pressured on" between the guard and the pommel. While this is sufficient in many cases, the pommel screw alone can, after time with heavy usage, loosen up or strip, creating "play" and space between the handle and the guard, causing movement and disconnection. Therefore, all swords require routine inspection before you begin to play the form.

Dreeben demonstrates how a good "combat steel" blade is strong but still lightweight, flexing 30 degrees without bending or breaking. Notice the blade has "blood groves running down the sword." This imparts strength and lightens the weight while making insertion and withdrawal easier.

The Tai Chi Jian

The standard Tai Chi jian is a relatively light sword similar in respects to many European straight swords that are of the same stature. In our school, the proper weight of a Tai Chi jian is a pound and a half, give or take. There are heavier "combat steel" versions on the market. Their weight of three pounds or more preclude effective one-hand operation the way the Tai Chi jian form teaches you to flourish the blade with light smooth movement. The jian is a precise, well-balanced weapon that can be wielded at blinding speed when necessary. The blade should be flexible "spring steel," able to bend at least 30 degrees, then return to true: this is important. Real "combat steel" does not necessarily have to be heavy. High-quality steel with a strong tensile and temper is all that is required. The blade itself should not splinter or bend against impact with another weapon. Deep cuts can be inflicted using a very light blade at high speed. Even a dull blade can open skin like butter, so be careful. The jian was not designed to sever limbs or dismember a torso the way a heavy Japanese Katana (with its two-handed grip) can do.

|

| The author of average height — 5'09" — shows how a properly measured sword of 28 inches should not touch the ground at full arm extension. |

The length of the blade for an individual of average height should be 28 inches. If you are six feet or taller, then 30 inches or 32 inches is the desired length. This measurement is not just to "extend your reach." The reason for specified measuring of each practitioner's sword is to provide sufficient ground clearance. It's better to have a little shorter blade than one that is too long; otherwise, you will be inadvertently scraping the floor with the tip of the blade as you run the form or use a low block in sparring. This is why our school measures the length from the ground up instead of the opposite. Every individual is built differently (some with longer legs, some with shorter arms, and so forth), which makes a precise fit important.

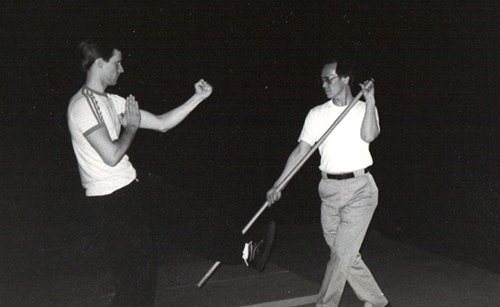

I learned my jian form from Matthew Leung at the International Tai Chi Institute in NYC's Chinatown back in the late '80s. I was a co-instructor there, teaching Chang style Tai Chi throwing applications. Sifu Leung was a disciple of the late master Franklin Kwong. Professor Kwong was a student of Yang Chen Fu and his eldest son Yang Shou. He also studied with two of Yang's top students, Chen Wai-ming and Dung Ying-chieh and was also a classmate of Cheng Man-Ching. It has also been reported that Kwong had the amazing ability to hold his breath for almost five minutes. One of my other sifus, Peter Chema, was also a student of Professor Kwong.

Professor Kwong played his Tai Chi jian form at a faster cadence than most, according to Matthew. Each movement and posture was taught with great detail in regards to body position, angle, coordinated energy and focus.

The traditional Tai Chi jian in and of itself is a complete sword fighting system which includes concurrent Tai Chi principles as they relate to a blade. The form is standardized amongst most Tai Chi schools and is generally a long set with many different sections. It is actually like several smaller forms combined into one long form. Each posture consists of one or more movements that focus on something specific. Other schools have repeat movements for more general applications. If you compare two different families' versions, while not identical, they still contain similar techniques and concepts that cover every range of movement. Studied, broken down and analyzed, the Tai Chi jian form is an encyclopedia of practical swordplay.

The principle defensive technique of jian is yielding, deflection and re-direction of the opponent's blade while applying energy from your legs through the waist into the sword for counterattack. You will find this core principle throughout the form. Each singular, deflective movement may have a cut, slash or stab built into the linear parry. Offensively, the straight thrust aimed at the enemy's center mass - from head to toe - is the primary lethal weapon. Slicing and cutting are defensive in nature and are executed to disarm or disable the opponent. Footwork patterns are active and angular, balancing short- and long-range steps and even containing leaping steps that cover a vast distance. In fact, if we contrast and compare the jian with other styles of Kung Fu, you can see the same or similar movement patterns emerging. Any sword form, from any style that is complete, will have a little something for everything. As a sword aficionado, you don't have to learn all the different forms to obtain this knowledge; just conduct a basic study and learn from the differences. One form, mastered, is all you need.

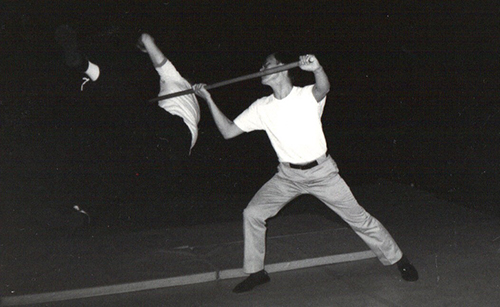

| Dreeben runs through "Triple bracelets embracing the moon," the postures just before the sword transfer. Notice how the sword slides through the fingers into the "contact guard" grip as the supportive hand's two fingers touch the meridian on the wrist completing the major star of the dipper. The hand transfer for "Major star of the dipper." |

The Proper Grip in Kwong's Version

The proper grip in Professor Kwong's style is established formally, at the beginning of the form between the third and fourth section when the sword is held in the reverse grip with the opposite left hand, then transferred to the right hand. The first three sections - "Step forward to unite the sword," "Immortal guiding the road," and "Triple bracelets embracing the moon" - leads to the sword transfer for "Major star of the dipper." Freezing this moment in time, we see transference of the left hand holding the sword in a reverse grip with the pinky and ring finger curled around the guard, the palm facing out. The right hand holds the hilt close to the pommel. Now two hands are holding the sword in a vertical position. The left hand releases, the handle slides through the right palm and the grip comes to rest with the guard flush against the forefinger and thumb knuckle. This is the key point. This "contact guard" is the proper grip in our jian. The form itself is teaching you how to establish it. Rewind to a little detail: simultaneously, as the hilt is sliding through the right palm from the pommel to the guard, the left hand has formed the "sword hand" (supportive hand) with the forefinger and middle finger extended. The two fingers brush against the meridian of the inside of the right wrist as the grip stops against the guard.

"Contact Guard" Compared to the "Fencing Grip"

What I loosely call the "fencing grip" is actually the most common way many practitioners hold the jian . One reason is because students first learn the form with a light wooden sword where the true weight of a metal sword is not felt. The fencing grip is usually a mid-handle grasp with the thumb and forefinger prominent as if you were holding a knife to cut your food. The Tai Chi jian has many intricate movements and the fencing grip gives you adroit precision of direction. It feels natural, like "it's all in the wrist," and it could be all in the wrist if you just stood there and manipulated the sword with just your arm and wrist. However, in Tai Chi jian, "it's all in the waist." The objective is to use unified and relaxed connected body movement in every move you perform, thereby creating a solid structure from any position that does not rely on isolated muscular strength. The "contact guard- grip" in our system forces you to articulate the finer sword moves by using your entire arm, waist and legs in a connected fashion. Do you play a section of your form that just does not feel right or feels weak? Chances are it's because you are not holding the sword correctly; check your grip and reassess it.

How to Determine the Proper Sword Grip

Any style of sword grip, whether it's the contact guard, fencing, etc., should meet the criteria of specific attributes that you would need to use the sword in actual combat. Here are some points to consider:

Does your grip alone provide "special awareness" of where the blade's sharp edges are at all times while you are playing the form? A cut should "whistle," not "whoosh," as the blade flies through the air. You should always be able to "feel" the edge without looking at your hand to see the cant of the blade (never take your eyes off the target). Some manufactures build lined grooves into the handle like Braille so you can feel blade orientation. Round smooth handles often do not provide this awareness. With the guard in the crease of your thumb and forefinger you can feel the cutting orientation without having to look at the blade.

The handle should not inadvertently rotate in your palm while you run the form because this will change the cutting direction. You should be able to go from a soft grip to a hard convulsive grip without blade rotation.

Can your style of grip withstand extreme impact from a heavy weapon? The heel of your palm should be sending the compression into your arm bones for support rather than letting the bones in the hand shoulder most of the load. Next time you perform dips and chins, pull-ups, or even hold a dumbbell or kettlebell, notice how your hand aligns up slightly to line up the palm with the wrist for a direct connection for body weight support.

A common two-handed supported grip in the form with multiple applications.

Fine Points

Most martial artists who perform a lot of sword-versus-sword or sword-versus-different-weapons sparring automatically start to adjust their grip close to the guard in this manner. One reason is extreme hand fatigue that starts to set in during heavy combat. In many cases a player will actually have to switch hands due to cramping and weakness of the fingers. "Choking up" on the grip instinctively gives you better support.

Your grip should be firm and secure but not convulsively tense. Otherwise your hand will fatigue very quickly. The goal is to cultivate adroit sensitivity in your entire hand that holds the sword from the palm to the fingers, thereby extending your qi into the blade. There are times when you might extend your index finger to direct energy and placement. With the contact guard you still maintain stability as the guard rests against your index finger knuckle. Similarly, you may release then tighten your pinky and ring fingers to produce a torqueing-whipping energy while your other two fingers and thumb still maintain a firm grasp.

Different sections of the sword form have the opposite hand assisting specific cutting strokes or thrusts. This could be with the two finger "sword hand" touching the wrist, offering a focused energy from both arms like a spotter helping you at the gym, or supercharging a stroke with your second hand grasping the extended handle and pommel for maximum force. The contact guard provides plenty of space for your second hand to grab the remaining handle. In the ending section of the form the supporting hand places the base of the palm in the center of the pommel for an upward thrust that puts the entire body behind it, again relying on bone structure through alignment, not just sheer muscle.

A supported grip for an upward thrust. Notice how the pommel rests against the heel of the left palm with stability coming from the skeletal structure of the left arm.

In Professor Kwong's form, some postures have the first third of the blade laying on the forearm of the opposite arm for close-range supported thrusts and cuts. One movement actually has your knee bumping the flat part of the blade, knocking it upward to assist in leverage against a heavier weapon, while you are taking a leap forward with that same leg. The knee-bump assist could also be used to help withdraw the blade stuck in an impaled torso or fire a kick while manipulating the blade.

The Tassel

Tassels are pretty and flamboyant and are included in some styles and families sword forms. They are found on swords in many different cultures, often serving as a lanyard. Tassels are ubiquitous with Chinese jian; however, I believe they have no place in practical sword combat for two reasons: one, the tassel can flip up into your eyes, hindering your vision (because unlike the fixed sword form, sword sparring is unpredictable and the tassel can fly anywhere); and two, your opponent could grab the tassel, yank on it, get control and gain an advantage. The tassel can tie up on your arm and get caught on things. Most often, tassels are only for swords made to be hung in your house for good Feng Shui. In Kwong's style, we do not employ the tassel, nor does he have one on his sword in the YouTube video. In fact, many famous masters of old forgo the tassel.

|

| Starting your form with the sword lying on the front of your arm (as some other families do) places the sharp tip dangerously close to your eye. |

Placement of the Blade during the Opening Sequence

All Tai Chi jian forms begin the sequence by holding the sword vertically and lying either at the front or rear of the left hand. Why is this done this way and what is the significance here? Historically, it signifies the option to carry the sword out of the scabbard, ready for action yet without fatiguing the right sword-fighting hand by having to hold it for a prolonged period. The vertical carry position produces the least amount of fatigue. With a simple change of hands, the sword is at the ready. Knowing there is a possibility that an enemy might catch us by surprise, the sword form teaches us several defensive movements holding the sword in this reverse grip before we perform the transfer to the right hand.

In Kwong's form, the sword is held along the underside of the arm on the back of your body. Other schools have the blade positioned along the inside of the forearm on the front of your body. With the blade in front you can transfer the sword to the right hand a second faster than you can if the blade is lying on the back side of the arm. But today, who cares about that whole second? We do not carry around a sword for personal defense anymore. I cannot emphasize this enough: blade in front is very dangerous! It makes no sense to me why you would hold a pointed blade inches from your eye, as these other schools do. You could easily self-inflict an injury by accident from this position. Holding the blade along the back of your arm makes this accident relatively impossible.

Shape of the Guard and Why Is It so Small?

The size of the guard on the Tai Chi jian is rather small compared to most European counterparts. You might think, "Why not make the guard larger to offer the sword-wielding hand more protection?" After all, most classic foils, epees, rapiers and sabers have large cup guards, some even with long quillons protruding from them protecting the entire hand.

The major difference and the reasoning behind the smaller guard is not to hinder the jian's close-range application. Other than in a clinch, most European swords are used at distance. For close range, one would pull out a dagger. At one time rapier and dagger was a popular two-handed match-up. The smaller guard of the jian with its smooth edges allows you to manipulate the weapon close to your body in many fashions. A substantially larger guard would limit this type of close-range defensive movement. The traditional jian form contains an entire close-range fighting system with techniques for every possible angle around the circumference of your body. And the left empty hand plays an active role that is not restricted and limited by holding a second weapon.

Personally I prefer the guard slanting away from the hand design for its immediate utility. Having the ability to momentarily trap an opponent's blade on the guard's edges gives me more options at the moment, especially to disarm the opponent. Slanting towards the hand limits the opponent's blade to always sliding off, and possibly into your arm, wrist or body. You might be of the mindset that "I don't want the opponent's blade to get hung up on the guard" during an exchange, and that's cool. Whatever works for you. By comparison, the solid, diamond-shaped guard can provide more weight and counter-balance to the sword but does little to stop a blade either. If you decide to opt for the slanting backwards guard, make sure the edges or quillons don't dig into your hand when you establish the proper "contact guard" grip.

As a student of the Tai Chi jian, it would behoove you to screen as many videos on YouTube of all the masters playing their jian. Take note of how and where they are gripping their weapon. Study the finer details of their movement - the waist turning, the weight transitions and their posture. Compare and contrast to what you are doing and see if it is better. See if you can learn something and improve your Kung Fu!

As a footnote, expand your consciousness and engage your right brain. If you are right-handed, teach yourself the sword form left-handed. I am a "lefty" who learned thejian right-handed because it is a right-handed form, then taught it to myself left-handed. Consequentially, I get a more balanced workout when I play both sides and have no problem using either arm for sword sparring. There is a big tactical advantage to being able to switch the sword to either hand at will.

|

|

About

Robert Dreeben, with photos Amada Alcantara :

![]() Robert Dreeben is a well-known martial arts writer and instructor. He is also a 22-year veteran active member of the NYPD.

Robert Dreeben is a well-known martial arts writer and instructor. He is also a 22-year veteran active member of the NYPD.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article