The recent rise of MMA has caused many practitioners of "traditional" Chinese martial arts to wonder what this means for them. The responses run the gamut from those seeing MMA as the diametric opposite of traditional martial arts to those who wonder how Chinese martial arts can be incorporated into MMA. These are significant issues in the marketplace of martial arts, where attention is also translated into money in the form of student tuition and equipment sales.

The recent rise of MMA has caused many practitioners of "traditional" Chinese martial arts to wonder what this means for them. The responses run the gamut from those seeing MMA as the diametric opposite of traditional martial arts to those who wonder how Chinese martial arts can be incorporated into MMA. These are significant issues in the marketplace of martial arts, where attention is also translated into money in the form of student tuition and equipment sales.

In the longer history of Chinese martial arts, however, things haven't changed. Indeed, MMA seems in no way different from Chinese martial arts before perhaps the late 19th, or certainly the early 20th century. All martial arts were actually mixed back then, and they still are, though the very recent construction of martial arts styles tends to obscure this. Even when we look at most contemporary practitioners of Chinese martial arts, it is more common to find people who have studied several styles, or at least under several teachers. MMA makes explicit the way many martial artists actually train. It is a conceptual challenge only to those practitioners who want to believe in a single answer to the question: what martial art should I study?

This is not the first time that traditional Chinese martial arts have been challenged and found wanting. The earliest examination of the value of traditional martial arts is the well-known quest of General Qi Jiguang (1528-1588 戚繼光) in the 16th century to find an effective art to teach his soldiers. He looked at a number of schools and found them all wanting. Most, he felt, were effective in one respect, but not in others. Taken together they would form a complete system. Faced with this reality, he developed his own system to teach his troops.

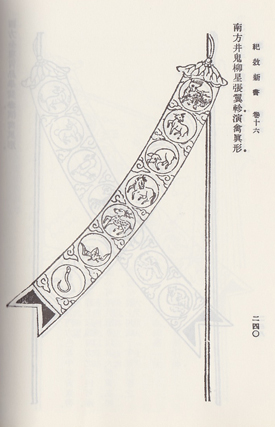

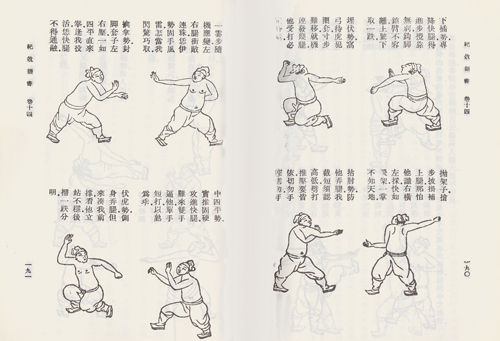

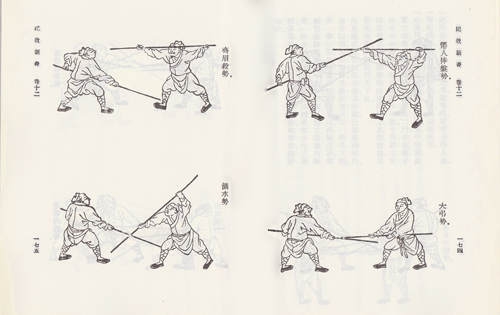

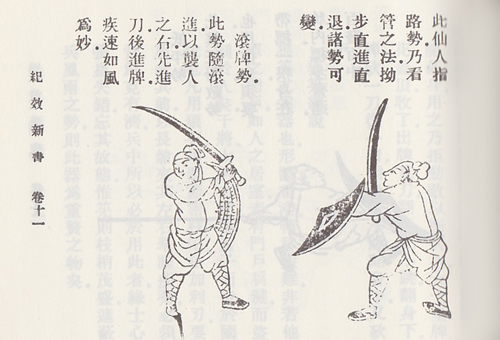

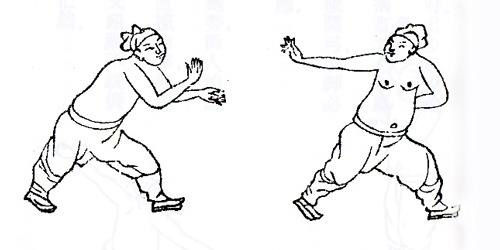

Qi Jiguang Jixiao Xinshu chapter eighteen, Boxing Classic 拳經

"From ancient times until the present, among boxers, Song Taizu had 32 position Long Fist. There were also the named positions that Six Paces boxing, Monkey boxing, and Transformation boxing each called what they did; the similarities are great, the differences small. At present [there are] the Wen Family Seventy-Two Movements boxing, Thirty-Six Interlocking, Twenty-Four Dispelling Reconnaissance, Eight Lightning Changes, and Twenty-Four Short. These also are the best of the best. Lü Hóng's eight takedowns although hard do not reach the limit of Zhang's short striking, Shandong Li Half the Sky's kicks, Hawk Talon King's grasp, Thousand Fall Zhang's Falls, Zhang Bojing's strikes, Shaolin Temple's staff and Qingtian's staff techniques, together with Yang family spear technique and Bazi boxing's staff are all currently famous.

"Although each has choice aspects, one has the top but not the bottom, or the bottom but not the top, so one can achieve victory over someone without this surpassing the bias of one viewpoint. If each school's boxing techniques could be taken together and practiced, then it would be like the true Mount Chang snake technique: strike the head then the tail will respond, strike the tail then the head will respond, strike the body and the head and tail will mutually respond."

古今拳家宋太祖有三十二勢長拳又有六步拳猴拳囮拳名勢各有所稱而實。大同小異至今之溫家七十二行拳三十六合銷,二十四棄探馬,八閃番,十二短。此亦善之善者也。吕紅八下雖剛未及線張短打, 山東李半天之腿, 鷹爪王之拿, 千跌張之跌,張伯敬之打?少林寺之棍與青田棍法,相兼楊氏鎗法與巴子拳棍皆今有名者。雖各有所取,然傳有上而無下,有下而無上就可取勝於人此不過偏於一隅.若以各家拳法兼而習之正如常山蛇真法擊首則尾應擊尾則首應擊其身而首尾相應

It is important to note that in this passage Qi Jiguang does not discuss martial arts "styles" but rather schools, or people following a teacher. He uses the term jia (家), which literally means a house, family, home or relatives. It can also mean, as a suffix, one who does something. He therefore discusses boxers or pugilists (拳家), the first term quan (拳) means "fist", and here referring to those who use the fist. More broadly this can also mean unarmed combat, and sometimes martial arts including weapons. Usually, however, in traditional Chinese sources, unarmed striking combat is distinguished from wrestling and the various forms of armed combat. The terminology of traditional Chinese martial arts separated particular skills, striking, wrestling, fencing, archery, etc. Qi Jiguang is our first written record of different schools within those skills groups.

When we look at most modern martial arts styles, we see many different approaches to the reason for practicing martial arts. This goes beyond the simple stress on being more "practical" in the sense of being more oriented to self-defense. What sets the martial arts apart from other physical skills is the "martial" part. The motions of a martial art are predicated on combat even if a particular practitioner is not striving to improve his self-defense abilities. One does not simply wave one's hand in a certain way because it looks nice; one does so because it has some combat function. Because of this, all martial arts have a combat rationale to explain why they do what they do. Some people might even call this a "theory" of combat, but that is perhaps too strong a word.

Rather than a "theory," I prefer to understand each style or art as having a "script." This script describes what would happen if the martial artist encountered a combat situation. It includes not only how one would react, but also how one would be attacked. The student is provided with an explanation of how the art or style has all the skills one needs in a fight because combat will occur in a specific manner for which the art or style provides a response. Hence, if I practice a striking art I am told that I will win the fight through striking and need not develop ground fighting or grappling skills. Similarly a grappler is told that, even if he might take a few blows on approach, once he gets to grips with his opponent he will win.

It seems that every style can also provide anecdotal evidence that their script is accurate. Master so-and-so encountered a combat situation and easily defeated his attacker or attackers. To that store of positive anecdotes proving the superiority of one style's script are added negative anecdotes of other style's failures. A master in that other style encountered a combat situation and, because his style's script was wrong, he was beaten. This extends to encounters between styles. Youtube abounds in video encounters between different styles, each accompanied by extensive commentaries explaining why one side or the other succeeded. The comments most often turn on the quality, training or experience of the individual practitioner versus the value of the art they claim to represent, or the relative merit of a particular style. Occasionally someone will suggest that martial arts is about more than just fighting.

At the risk of offending a large number of people's strongly held beliefs, I will make two points. First, after many years of trials and debates, no martial art has emerged as perfect and invincible to anyone outside of its own practitioners. The same can be said for fighters. There are many great fighters, but even the best is not invincible even during their prime. Second, if the only measure of a martial art is its effectiveness in combat, then most of us, myself included, may well find that we are fortunate enough to have been wasting our time in training. If we never fight for real, then why have we spent so much time, effort and money over the years practicing martial arts?

Returning to Qi Jiguang, we must keep in mind that General Qi did not expect his men to be invincible, just effective. In real battle even good fighters may lose. Qi Jiguang's men were soldiers whose job it was to fight pirates raiding China's coast. They studied martial arts in order to fight armed men. It is probably for this reason that General Qi removed the unarmed combat section from his manual when it was later reprinted. At least for a soldier, unarmed combat was a much less important skill than armed combat or any number of other important soldiering skills. A military commander is faced with the choice of which skills his soldiers need. Granted that it would be ideal to have a soldier capable in every possible skill, limitations of time, money and the human resources require choices. Which skills are the most important?

Unlike many of our contemporary discussions of martial arts and their respective effectiveness, Qi Jiguang's critique did not have nationalist overtones or personal economic concerns. He was solely interested in producing effective combat soldiers with the least amount of time and effort. They would fight in real life-and-death battles with other armed groups of men, and Qi Jiguang's training methods would be tested in combat. To the extent that he was ultimately successful in suppressing the pirates, his training methods were effective. The product of his investigation of the martial arts was not a "style" but a system of combat training; when he later revised his system, he removed both the armed and the unarmed combat training sections.

Unlike many of our contemporary discussions of martial arts and their respective effectiveness, Qi Jiguang's critique did not have nationalist overtones or personal economic concerns. He was solely interested in producing effective combat soldiers with the least amount of time and effort. They would fight in real life-and-death battles with other armed groups of men, and Qi Jiguang's training methods would be tested in combat. To the extent that he was ultimately successful in suppressing the pirates, his training methods were effective. The product of his investigation of the martial arts was not a "style" but a system of combat training; when he later revised his system, he removed both the armed and the unarmed combat training sections.

MMA has challenged traditional Chinese martial arts not simply as a new martial art in an already crowded market, but because it is so well promoted. Professional MMA fighters train the way professional athletes do, with much greater frequency and intensity than all but a few traditional martial artists. Someone who trains three times a day, working on their strength, conditioning and the incredibly broad range of fighting skills their sport requires is, in fact, a serious martial artist. Moreover, they get to demonstrate their skills on national television. It is not surprising that a martial art with that much publicity will garner many interested students.

At the same time, many traditional martial artists are turned off by MMA. It is too much of a sport, too focused on fighting, and entirely lacking in the positive values and practices of traditional martial arts. Some argue that MMA is not as effective in real self-defense situations because it is designed for the ring rather than the street. Others argue that it is wholly derivative of traditional martial arts and therefore offers nothing new. Even if these critiques were true, this would still leave traditional martial arts in a strange place.

Unlike Qi Jiguang, strict traditionalists choose not to examine what they are doing in light of an external standard. Their perspective is that their style as they understand it represents not just a repository of correct practice but a complete repository of correct practice. At some point in the distant past, someone developed a perfect style that operated as an integrated, flawless system of fighting. This style was then transmitted flawlessly from master to student until today. What Qi Jiguang did in the 16th century was not to question the value of the traditional schools he found, but to realize that even the best were only part of a larger whole. For his very specific purposes, training soldiers to fight pirates, he drew upon the existing schools to formulate a hybrid system, an explicitly mixed martial art, which included both armed and unarmed combat skills. Qi Jiguang's system, in turn, influenced other martial arts, some of which may be practiced today.

Ultimately, the very fact that MMA has become such a brand name, and is usually built around a standard set of martial arts (Brazilian Jiu Jutsu, Muay Thai, Western boxing, and wrestling), shows that it is well on its way to solidifying its own "tradition." We may soon see "traditional" MMA schools defining the techniques and practices that are "authentic" and those that are not, just as any other traditional school does. Individual teachers will create franchises with rigid training regimens and belt systems to serve a practicing public that expects that sort of thing. For the purposes of training, Qi Jiguang created a system of martial arts out of the arts at his disposal in southern China in the 16th century. So, just like traditional martial arts, MMA has a history, and techniques drawn from earlier martial arts. And traditional martial arts have techniques that have a future not because they have a history, but because what they do has value.

About

Peter Lorge :

![]() Peter Lorge is a historian of 10th and 11th century Chinese, with particular interest in Chinese military, political and social history. He is Assistant Professor of History and of Asian Studies at Vanderbilt University, as well as the author of Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century.

Peter Lorge is a historian of 10th and 11th century Chinese, with particular interest in Chinese military, political and social history. He is Assistant Professor of History and of Asian Studies at Vanderbilt University, as well as the author of Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article