Why Practice Tai Chi

Why Practice Tai Chi

The pace and nature of modern life, while providing numerous benefits, can lead to a wide variety of chronic illnesses and work-related ailments unique to our times. Ironically, the very technology intended to make our lives easier has, if anything, compounded our daily stressors. Along with dramatic increases in the pace and volume of work in today’s world, the range of movements made by most modern professionals throughout the day has also become severely limited. Few professionals are immune to this one-two punch. Engineers, lawyers, accountants, computer programmers, and real-estate professionals, to name a few, are all invariably subject to the devastating effects of increased stressors and restricted movements.

High blood pressure, insomnia, migraine headaches, chronic anxiety, depression, exhaustion, memory issues, obesity, deteriorating vision, sore muscles, bone/skeletal issues, immune system disorders – these and many other health issues are on the increase due to stress and a sedentary lifestyle. Stress can dramatically impact work efficiency, creating a vicious cycle where inefficiency leads to a greater workload, causing more stress, even worse decision-making, an even heavier workload, etc. Stress is a major poison, seemingly inescapable in the modern world, causing mental suffering and a wide variety of psychosomatic illnesses.

Fortunately, as with most poisons, antidotes exist. Taijiquan (太极拳), “Tai Chi” for short, is one such antidote if practiced correctly. Tai Chi can reverse if not cure all of the above-mentioned chronic illnesses. It also has the added benefit of being an effective martial art, if one learns from an authentic master of the art.

Health and Martial Benefits of Tai Chi

Tai Chi can cure the underlying causes of such illnesses, not merely their symptoms. According to Eastern medicine, many modern-day chronic illnesses are caused by blockages in the body's energy pathways, or “meridians,” as a result of long-term stress, which fundamentally compromises our immune systems. Through the practice of movements based on Tai Chi principles, our energy pathways can be systematically unblocked and re-opened. This reduces stress, allowing our immune systems to regain full functionality while also helping our central nervous systems to regenerate.

Tai Chi can also be a highly effective type of martial art if taught in a traditional manner. Unfortunately, in modern times most Tai Chi teachers and students alike practice very watered-down versions. Many people believe that Tai Chi is just a basic exercise done for health, something only the sick or elderly practice in the park. But this is a misconception arising from the hollowed-out versions of Tai Chi that are taught everywhere. Although such "park versions" are easier to learn (a fact that very likely accounts for their rapid spread) and still have health benefits, the traditional practice of Tai Chi can offer so much more.

While it typically takes much longer to master Tai Chi than to master external styles of martial arts, some of the best martial artists in the world are traditional Tai Chi stylists. True Tai Chi masters can, in fact, perform phenomenal feats that almost seem magical to those who don’t understand the underlying principles at work.

An Introduction to Traditional Styles of Tai Chi

Before discussing those principles, it might be helpful to briefly discuss the various traditional styles of Tai Chi. Before doing so, it should be emphasized that all styles of Tai Chi can provide the above-mentioned health and martial benefits, if taught by authentic teachers in a traditional manner.

There are many traditional styles of Tai Chi. The most common are the Chen (陳), Yang (楊), Wu (吳), Wu (武), and the Sun styles (孫). Another increasingly popular traditional Tai Chi style is Zhaobao (趙堡). This is the style that the author of this article practices.

Although Tai Chi has a complex history, with numerous disputes surrounding the origins of the various styles, this article will attempt to summarize the basics of such origins, in hopefully as uncontentious way as possible.

Chen Tai Chi

Chen Style Tai Chi was developed by a general of the Ming Dynasty named Chen Wangting. According to historians from Chen Jia Gou Village (Chen Village) located in China’s Henan Province, Chen Wangting created Tai Chi in general.

Zhang Sanfeng

This history is disputed by other historians, especially Daoist monks from the Wudang Temple. They assert that the semi-mythical Daoist monk Zhang Sanfeng invented Tai Chi. Whatever the case, Chen Tai Chi is undisputedly connected in some way to almost all styles of Tai Chi. Chen Tai Chi is also distinguishable from all the other styles due to its incorporation of explosive striking movements in its forms, known in Chinese Mandarin as fajin (發勁).

Chen style Tai Chi was a closely guarded secret for much of its history, taught only to other Chen family members living in Chen Village. This changed after Yang Luchan came along.

Yang Tai Chi

The Yang Style of Tai Chi was developed by the famous Tai Chi practitioner Yang Luchan.

Grandmaster Yang Luchan’s teacher was Chen Changxing, a 6th generation Chen style master, who bucked the trend of only teaching the art to other Chen family members. Due to Yang Tai Chi’s fundamental differences with Chen Tai Chi, some historians question whether Chen Changxing taught Yang Luchan traditional Chen Tai Chi (which Yang Luchan then changed), or something different.

|

|

| Grandmaster Chen Changxing | Grandmaster Yang Luchan |

Whatever the case, after Yang Luchan mastered the art Chen Changxing taught him, he began openly teaching Tai Chi to students in Beijing, where he became so well known for his martial prowess that he took on the nickname Yang Wudi (楊無敵), literally meaning “Yang without enemies.”

It is from Yang Luchan that Tai Chi began to flourish and spread throughout the world. In fact, the name “Tai Chi” originates from Yang Luchan’s efforts in teaching this art. Today, the vast majority of Tai Chi practitioners practice the Yang style of Tai Chi. This is the most common Tai Chi style performed in parks.

Zhaobao Tai Chi

The Zhaobao style of Tai Chi is an independent style of Tai Chi, with its own distinctive history and flavor. Zhaobao Tai Chi originated over four hundred years ago in Zhaobao Village, located less than ten kilometers from Chen Village. It ultimately traces its history back to the Wudang Mountains, claiming as its founder the above-mentioned Daoist monk Zhang Sanfeng. Due to inaccurate historical records, however, the first official figure in its lineage is an individual named Wang Zongyue, who was removed by many generations from Zhang Sanfeng.

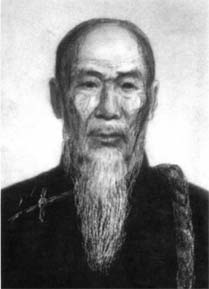

He ZhaoYuan

For most of its history, Zhaobao Tai Chi was not taught outside of Zhaobao Village. It wasn’t until the 1950s, after two 10th generation masters, Zheng Wuqing and Zheng Boying, moved from Zhaobao Village to the city of Xi’an that it first began to spread throughout China.

Master Zheng Wuqing was the first practitioner to call this art “Zhaobao Tai Chi.” Prior to this time, it was often referred to as the He (和) style, after Zhaobao Tai Chi’s 8th generation master, He Zhaoyuan. He Tai Chi is still taught today in China, having been adapted and spread by He Zhaoyuan’s children. As most of the famous masters in Zhaobao Tai Chi’s lineage were not related to one another, however, and Zheng Wuqing himself was not from the He family, Zheng Wuqing believed a neutral name to be more fitting.

Wu, Wu, and Sun Styles of Tai Chi

The Wu (吳) style of Tai Chi undisputedly originated from Yang Tai Chi, as its founder Wu Quanyou was directly taught by Yang Luchan and his son, Yang Panhou. Note that there are two styles of Tai Chi that are called "Wu." The Chinese characters are different so the words are different, but they are homophones when transliterated to the alphabet.

Wu Quanyou

The other Wu (武) style and the Sun (孫) style of Tai Chi both have more complex origins. They are directly connected to both the Chen and Zhaobao styles of Tai Chi, through Chen Qingping. Chen Qingping is the 7th generation master in Zhaobao Tai Chi’s historical lineage. After marrying a girl from Zhaobao Village and permanently relocating there, he learned Zhaobao Tai Chi from its 6th generation lineage master, Zhang Yan. Chen Qingping grew up, however, in Chen Village, and was also said to have learned the “small frame” Chen style created by Chen Youben. Because of his connection with both styles, there is an ongoing tug of war between these two styles regarding what he ultimately taught, which is outside the scope of this article.

It should be noted, however, that these two styles also have an indirect connection to Yang Tai Chi, through its founder Yang Luchan, who referred Wu Yuxiang, the founder of the Wu (武) style and the grandfather of the Sun style, as a student to master Chen Qingping.

The very fact that different Tai Chi styles have heated debates over attribution inherently shows that Tai Chi has great merit. Otherwise, it would have likely long since disappeared and few would care who taught what to whom.

But how does Tai Chi work?

Wu Yuxiang

While entire volumes can and have been devoted to this topic, here is a general, overarching theory of Tai Chi. Essentially, mastering Tai Chi requires the long-term cultivation of the body’s natural internal energy, commonly known as “qi (氣, pronounced “Chee”)”, along with the application of this energy through correct body mechanics.

All living creatures have qi energy. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t be alive. In most living beings, however, that energy is present in much weaker forms than our bodies are capable of producing, storing, and using. Due to China’s unique history, with its grounding in Daoism and Buddhism, along with their associated meditation practices, the ancient Chinese long ago discovered and systematically (one can even say “scientifically”) began to develop exercises to better understand, cultivate, and utilize this natural energy.

Just like an average person can’t expect to walk into a gym and bench press 300 pounds without having trained before, the cultivation of internal energy isn’t something that typically just naturally happens. It must be developed systematically by engaging in exercises that train the body to move in ways specifically geared to open up, and keep open, the body’s energy pathways, and to generate the energy that flows through these open pathways in ever greater amounts over time. This allows the body to move and apply energy in an integrated, holistic manner.

In the way of martial applications, those who have attain advanced proficiency in Tai Chi can move quickly and agilely during combat. They can also apply a great amount of power in their strikes, doing so in a relaxed manner, similar to how whips work. Most of the energy that advanced Tai Chi practitioners use, however, comes directly from their opponents. Such energy is often either redirected into the ground, and then back up, or else bounces back to their opponents in an otherwise circular fashion, more akin to how springs work. Advanced practitioners can also utilize subtle grappling techniques (qinna 擒), bringing the full weight of their body to bear on their opponent's small, weak spots.

Many of Tai Chi’s health benefits can be attributed to better blood flow.

Diligent Tai Chi practitioners often experience increased blood flow through practice. In fact, the terms “energy” (qi氣) and “blood” (xue 血) are frequently used in conjunction with one another in Chinese when describing the internal mechanism of Tai Chi. Such increased blood flow provides much needed nourishment to a practitioner's internal organs.

Just like crops will wither if their irrigation ditches become blocked, a person's internal organs will be negatively affected if their energy pathways become blocked, due to stress, poor postures, bad habits, negative emotions, etc., over a long period of time. Once practitioners learn to unblock these pathways through correct movements and mindfulness, their blood and energy (i.e., qixue 氣血) can begin to flow again, re-nourishing parts of the body that had begun to fail due to such blockages. One direct benefit of this, among many, is the regeneration of the central nervous system. This allows Tai Chi practitioners to react more quickly and have better balance as their minds become more connected to their bodies.

Tai Chi practitioners also progressively learn to engage only the minimally necessary muscles to maintain correct posture and movements, which enhances their overall efficiency in using energy. As practitioners save more energy than they use on a daily basis, their energy begins to accumulate, and their internal vitality grows, improving their health, mental clarity, and mood.

More than just a simple exercise, Tai Chi is a philosophy and way of life. When practitioners truly start to understand the essentials of its underlying teachings, they begin to live in more mindful ways, constantly striving to avoid negative emotions and instead cultivate positive energy through their everyday activities. This has a beneficial impact on the above-mentioned psychosomatic illnesses far beyond Tai Chi exercises practiced in isolation.

Finding a Good Teacher

For those interested in learning Tai Chi in its traditional form, it is essential to find an authentic teacher.

To determine whether a sifu teaches a traditional style of Tai Chi, check for the following basic elements in the curriculum: 1) standing meditation exercises, known as the “post-standing” (or in Chinese, zhanzhuang 站桩); 2) forms (especially longer forms, such as those having over 70 movements, or progressive, smaller forms that train different aspects and build on one another); and 3) Push Hands.

It would also be beneficial to test the teacher for legitimate martial skills applied with little effort and that cannot be avoided. Good teachers should apply just enough force to assess a student's knowledge, without hurting them.

Since Tai Chi takes a long time to master, also make sure the teacher’s personality and the class environment as a whole is a good fit for one’s own personality. As mentioned above, the teacher should incorporate Tai Chi philosophies into his or her own lifestyle.

About

Timothy A. Griswold :

![]() Timothy A. Griswold was a Chinese linguist in the Army, and is a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–2004). He is also a former active duty Air Force JAG officer and currently a major in the Air Force Reserves. He has had a life-long interest in the internal martial arts, especially Tai Chi, and currently runs a law firm in Milpitas, California. For more information, see GriswoldLawFirm.com.

Timothy A. Griswold was a Chinese linguist in the Army, and is a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–2004). He is also a former active duty Air Force JAG officer and currently a major in the Air Force Reserves. He has had a life-long interest in the internal martial arts, especially Tai Chi, and currently runs a law firm in Milpitas, California. For more information, see GriswoldLawFirm.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article