By Gene Ching with Gigi Oh

America wrote th e right to "keep and bear arms" in her Constitution. The battle to keep that right is a heated national debate now. When the Second Amendment was ratified in 1791, the kind of arms Americans had the right to keep and bear was left ambiguous. Part of today's argument focuses on technological advancements. Firearms have come a long way in the last 222 years. But what of the banned weapons that have not evolved? What about the banned traditional weapons? Many martial arts weapons - cold arms, not firearms - have been illegal for decades, regardless of Constitutional rights. Since Bruce Lee ignited the Kung Fu boom of the seventies, nunchuku have been banned in several states and regions. In subsequent years, other martial arts weapons were banned including shuriken, keibo (Japanese telescoping batons), Pilipino butterfly knives and many more. Some allowances were made for martial arts schools because the practice of these arts are part of a cultural heritage; but if a cop catches you carrying one on the street, you're likely to get it confiscated and lucky not to get cited. In America, where any upstanding citizen may carry a gun, it seems a little absurd.

Most illegal weapons are banned because of their association to gang violence. In the wake of Bruce Lee, nunchaku became fashionable, or at least associated with that nefarious section of society. Other banned weapons, like brass knuckles, sap gloves and blackjacks, have minimal connection to the martial arts but are associated with gang violence as well. Additionally, many regions banned weapons that can be carried covertly and drawn quickly; these include switchblades, gravity knives, and arguably keibo and Pilipino butterfly knives. Also in that category are the hidden blades: belt-buckle knives, lipstick-case knives, writing-pen knives, shobi-zue (a baton concealing a blade) and, of course, cane swords. This category of arms are typically classified as concealed weapons in the eyes of the law. In many states, qualified individuals can be licensed with a CCW permit (carrying a concealed weapon) for firearms, but that does not necessarily cover carrying any of the aforementioned weapons.

The illegality of cane swords is thought-provoking because, as any Kung Fu practitioner knows, the cane is a weapon on its own. The blade isn't necessary. Not only can the short stick methods propounded by martial arts styles from Escrima to Kobudo be applied to cane, but several styles of Kung Fu practice methods specifically for cane combat. Numerous Kung Fu schools have a wide variety of different cane forms. The Bodhidharma cane is a signature weapon of Shaolin Kung Fu. While one could argue that belt buckles and writing pens could also be used as weapons sans blade, that would be extrapolating techniques from more conventional weapons like chain whips and daggers. The tradition of cane fighting is well established in many martial methods. However, it would be absurd to ban canes.

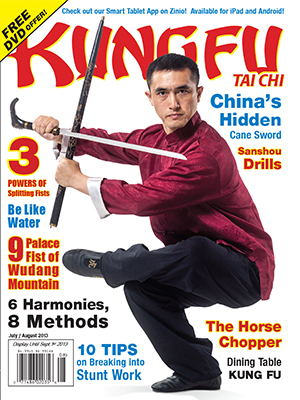

A cane that conceals a blade is a different matter entirely. While the cane alone can be used as a weapon, it projects a less lethal image because it's a blunt weapon. A sharp blade changes everything. In Europe, cane swords rose to fashion during the 18th and 19th centuries. A walking stick was already the mark of a European gentleman, and with the rise of personal firearms making overt sword-bearing obsolete, the sword became a covert feature of the walking stick. In Kung Fu, while there are plenty of swords and several canes, the cane sword is very rare. It was never as fashionable as it was in Europe, but that doesn't mean it didn't exist. Master Zou Yunjian (鄒雲建) practices a cane sword method called Nine Palace Crutch Cane Sword (Jiugong guaizhangjian 九宫拐杖剑). This comes from a traditional internal art descended from Wudang Mountain known as Jiugong Quan (Wudang Nine Palace Fist 武当九宫拳).

A Modern Wushu Champion with Traditional Roots

Master Zou is an unlikely proponent of traditional internal style because he was a world champion in Modern Wushu. He served on China's National Wushu Team from 1998 to 2002. In that time, he won gold medals at four major international wushu competitions: The 12th Asian Games held in Thailand in 1998, the 5th World Wushu Championship held in Hong Kong in 1999, the 5th Asian Wushu Championship held in Hanoi in 2000, and the 3rd East Asian Games held in Osaka in 2001. These were won in one of the more controversial divisions of Modern Wushu for traditionalists, the internal style of Taijiquan. Zuo won his titles when Modern Wushu was just beginning to introduce nandu (difficulty degrees 难度), a scoring method based on extreme acrobatic and gymnastic movements that many Taiji practitioners feel fly in the face of the fundamental principles of internal style. However, to dismiss a Modern Wushu proponent for not understanding Traditional Kung Fu is a grievous error. Zuo stands among a community of outstanding masters who have a firm grasp on both Modern Wushu and Traditional Kung Fu.

Zuo was a huge fan of martial arts from childhood. He grew up studying martial arts books and magazines in his spare time, from which he taught himself. Through reading, he learned Malitang qigong (马礼堂气功). He even learned some hard qigong on his own. He still credits his reading as laying the foundation for his understanding of internal theory. However, as a youth, Taiji was not his direction. Zuo was a fighter and wanted to pursue Sanda (free fighting 散打). But when Zuo's city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province, made selections for their municipal team, they only took forty applicants and he failed to make the cut. Nevertheless, Zuo struggled on the sidelines, practicing Sanda, Modern Wushu and dao (broadsword 刀), hoping for a shot at a team slot. "We used to fight a lot outside," confesses Zuo. "It was a bad influence. There were a lot of challenges at Wuhan." The coaches turned a blind cheek to it, probably covertly hoping that their up-and-coming athletes would get some seasoning from the experience. For Zuo, it worked. He remembers once being intimidated by an impressive display of iron head qigong as a prelude to a challenge, only to discover that, in combat, an iron head practitioner's nose bleeds just like everyone else's. "Wah! So bloody," Zuo chuckles at the memory. "I learned that flexibility, distance and chance are most important in a fight."

Zou got his opportunity late in his competitive career, at the ripe old age of nineteen. A position opened on the Taiji team. "They thought I was too old at nineteen. Usually the B Team members are fourteen only." Nonetheless, Zuo seized his chance and worked extremely hard. By the first year, he felt he was the best member on the team, even though he still hadn't officially secured the position yet. He eventually succeeded in competition, which qualified him. He made the professional team in 1993. "We got promoted to a better cafeteria at the pro training center. There was basketball and ping pong. But I always stayed focused on fighting skill." Making the team brought him under the tutelage of one of the preeminent exponents of the internal style of Xingyiquan (形意拳), Grandmaster He Fusheng (何福生) and China National Team Head Coach, Master Zhao Yong (趙勇). "I feel very lucky to have had such great teachers," Zou reflects.

Zou remembers his first professional meet. At that time, Taiji competitors competed in forms in pairs, side-by-side, and a panel would judge the victor who would advance to the next round. Sitting at the judging table were some venerable elder grandmasters including Li Deyin (李德印) and Men Huifeng (门惠丰). "After we competed, they discussed it for a long time. One of the old-generation masters asked me if I learned traditional." Zuo confirmed their suspicions, and after some more deliberation, Zuo was declared the winner.

The Nine Palace Fist of Wudang Mountain

While Zuo was training with the Hubei Professional Team, he discovered a hidden treasure. He happened to see one of the coaches practicing with a big spear, a really big spear, one that was over twelve feet long. Extremely long weapons don't convert to Modern Wushu. When made from traditional materials, they cannot be lightened like competition swords or they become structurally unfeasible. Zuo was captivated by this spear play. "A big spear is good for releasing power. I tend to hold back in pushing hands. I don't really want to hurt anyone and (allow them) to save face. But I can put all the power out in big spear."

The coach was Wang Bingsheng (王炳生), an inheritor of the unique sect of Wudang Kung Fu called Jiugong Quan. Wang wrote a book on the subject, Jiugong Quan Fa (九宫拳法), which details the history and methods of the style. According to that book, legend claims that Jiugong Quan descends from a Daoist named Zhang Shouxing (张守性) who lived in the Hongzhi period of the Ming Dynasty (1488-1505 CE). Zhang is a prominent figure in Chinese martial arts, attributed as the creator of Wudang Taiyi Wuxing Quan (Extreme Second-Heaven-stem Five Element boxing 太乙五行拳). He was the 8th generation lineage holder of the Longmen Pai (Dragon Gate Sect 龙门派) and resided in the venerated Purple Cloud Temple on Wudang Mountain (Wudangshan Zixiao Gong 武当山紫霄宫). Zhang's lesser-known creation, originally called Xuanmen Zhang (literally "profound gate palm" 玄门掌) was allegedly based on a combination of Zhang Sanfeng's (張三丰) 13 Taiji postures, Daoist breathing methods, Daoyin (a Daoist system of exercises often compared to yoga 導引) and fighting techniques. This later developed into Jiugong Quan which included methods such as 18 Legs (九宫十八腿), Rotation 12 Methods (九宫旋转十二法), Vital Point 12 Secrets (九宫点穴十二秘诀), as well as sword, staff, spear and, of course, cane sword.

During the Qing Dynasty around 1848, a man from Xiangxiang, Hunan (湖南湘乡), Xie Jingwu (谢敬武), was living as a hermit on Bai Shifeng (白石峰 - this is a southern peak of Heng Mountain 衡山). During his seclusion, Xie learned Jiugong Quan from a Daoist temple. When he returned to Xiangxiang, he passed it to his son, Xie Weida (谢为大). The younger Xie's Kung Fu skills ultimately surpassed his father's, and he in turn passed it to his son, Xie Defan (谢迪凡). The third generation Xie's childhood friend was He Chunsheng (何春生), who was eventually brought under the tutelage of Xie Weida after many appeals by his son. He Chunseng and Xie Defan studied together. Understanding what a rare opportunity this was, He was very diligent, training every morning at daybreak, as well as studying Daoism and Traditional Chinese Medicine. After the revolution, He accepted many disciples and became famous for his Kung Fu. He Chunseng is the maternal grandfather of Wang Bingsheng, and naturally Wang studied directly under him.

For a while, Master Zuo studied with Coach Wang every morning. "It was pretty rare at first," reflects Zuo. "Wang only had a few hundred students in Wuhan. Jiugong Quan looks a little like Taiji, Xingyi… I learned the empty hand forms, dao, spear and cane sword. The system has a jian (straight sword 剑), but I didn't learn it. I had to stop. After I won the World Championship, my coach forced me to focus only on competition. I still applied the Daoist theory I learned from Coach Wang. I wanted to inherit and promote Jiugong."

The Nine Palace Cane Sword

When it comes to the cane sword, in characteristic form Coach Wang's book Jiugong Quan Fa, cites the classics. According to Wang, the usage of canes was documented in the Book of Rites: Royal Regulations (Liji: Wangzhi 礼记:王制), which is one of the five Confucian classics written during the late Warring States (5th cent.-221 BCE) and Former Han (206 BCE-8 CE) periods. There were regulations on who could keep and bear canes. A fifty-year-old officer was allowed to use a cane at home. Sixty-year-old officers were permitted to use a cane in their hometown. Septuagenarians could use a cane throughout the country. Octogenarians earned the privilege to use a cane within the Imperial courtyard. And the venerated nonagenarian would be honored by a visit from the Emperor at his own home.

Wang also claims that within the 5th century work, Book of the Later Han (Hou Han Shu 后汉书), one of the etiquette chapters discusses a scepter called a wang zhang (royal cane 王杖). The Emperor had local officers give each septuagenarian one. It was nine feet long and adorned with a jiu bird (dove or pigeon 鳩). It was believed that the jiu bird never choked, so this symbolized the Emperor's wish that the bearer would not choke. Also, by imperial command, anyone bearing a wang zhang was not held to the standard rules of etiquette. If they owned a small business, they were exempt from taxation. If anyone dared to take advantage of them, they were despised by the court. The bearer's social status was equivalent to an officer who received 600 stone of rice (equal to about 60 cups per month).

Wang goes on to extol how, in days of old, a cane was a symbol of stature and pride for the bearer. To Wang, the cane represents both veneration and authority. He also cites the venerated painter and calligrapher Sun Mofo (1884-1987 孙墨佛), who lived to 106 years of age and always carried with him an iron cane that weighed 8 jin (about 8.8 pounds). Curiously, Wang adds mention of Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837), considered to be Russia's finest poet and the father of Russian literature. Pushkin fought twenty-nine duels of honor, surviving all but his final one. Wang claims Pushkin had an exquisite cane that he used while walking, kept by his desk while writing and by his bed while sleeping. It never left his side. Pushkin used it as an exercise tool as well.

Wang praises the cane sword as a weapon of the Jiugong system. He says the martial artist can use it as a sword or a staff and that it is easy to carry. He states that Jiugong guaizhangjian mainly employs staff techniques with the addition of some dao and jian methods. The form has a complex pattern that weaves through and steps around the "nine palaces," characteristic of the style. In the form, the sword begins sheathed within the cane. After a few movements, the sword is unsheathed and both cane and sword are deployed as a twin weapon. Then the sword is re-sheathed back into the cane at the conclusion of the form.

The Five "Fulls"

Master Zuo hasn't taught the Jiugong cane sword form openly at his school yet. He teaches both Traditional Kung Fu and Modern Wushu, whichever fits his student best. "Modern Wushu people can learn traditional very quickly because their bodies are ready," comments Zuo. "They just need the principles. Modern Wushu is larger, more showy. Sometimes it is difficult to change to smaller, tighter movements … just the level is different." Being a former champion, Zuo has watched the progress of Modern Wushu Tai Chi with guarded optimism. "It's starting to improve, especially overseas. Every year - a little better. At least they show the breathing - the qi - it's a good start … (but) many don't know internal power in China. The competitors don't have fighting skill, don't have meaning. At my school, I teach the 'Five Fulls': Beautiful, Powerful, Graceful, Peaceful and Meaningful. Meaningful is most important. Always look for meaning in forms for fighting. It looks right, even if the judges don't know… I teach (my students) power and energy from qi, not just dance, not real soft. Use energy to be soft. Go inside. If students understand power and energy, they see the coordination. Know yourself first. Movement, then qi. Coordinate. Otherwise it looks like you want to sleep."

The practice of cane sword is a unique cultural heritage that is very rare. Like with many traditional arts, the hope is that it continues to be passed down for the enrichment of future generations. However, given its illegal status in some states and countries, please check your local regulations.

| Discuss this article online | |

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine July/August 2013 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2013 .

About

Gene Ching with Gigi Oh :

For more information on Master Zou Yunjian, visit his school website at o-mei.com.![]()

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article