By John Fusco

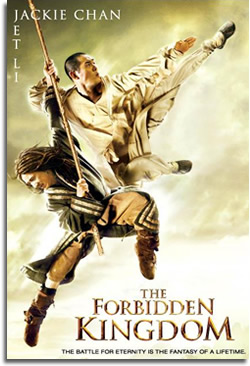

Rumble in the Jungle

Rumble in the Jungle

In the ruins of a fallen temple two supreme masters circle each other. One, a silent monk with a dark secret, white robes trailing like mist. The other, a bedraggled beggar rumored to be an immortal, and not just any immortal?one of the Drunken Eight. Indeed, his chaotic sway and stumble are shaman-like as he coils within the monk's tightening trigram.

This is not a point match; somebody's going to die here.

The Traveler observes from the temple shadows: a young foreigner, unsure of how he got to this place. A dream? Astral travel? Or, as the reputed Immortal suggested earlier over tea, a journey through the Zen "gate-of-no-gate", here to witness a test of skills between martial arts titans. Perhaps the Traveler, like Zhuangzi's butterfly, is in a dream within a dream, watching a battle of legends within legends. For the dueling adepts are none other than Jet Li and Jackie Chan.

For a moment, I am the Traveler: the westerner who has grown up on an unlikely fascination with Chinese literature, swordplay tales, and Run Run Shaw. I am here in Zhejiang Province, China, on a parboiling June day because I've written THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM and the cameras are finally rolling.

It's not just the historic union of Li and Chan that has me pinching myself; my fight scenes are being choreographed right here before my jet-lagged eyes by Master Yuen Woo-Ping and captured on film by the Oscar-winning cinematographer Peter Pau, the man who photographed CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON. My screenplay, I tell myself, is in the steady and deadly hands of this genre's Dream Team.

Jet, taking a cue from the page, sinks low with some Six Harmony Praying Mantis and deceptive Monkey footwork. Jackie counters with Shandong Black Tiger. They explode at each other in a dizzying, improvised blur, two men clearly exhilarated by each other's prowess and this long-awaited opportunity to bust open each other's bag of licks. If this was tennis it might be McEnroe and Borg. A blues bar: B.B. King dueling with Clapton. A boxing match: Ali and Frazier, pounding it out in Manila. Here, on the Hengdian backlot, the brawl has simply become known as "the J and J Fight," a fight that is now careening off the page, igniting into a blow-for-blow Hong Kong donnybrook that is vintage Woo-Ping; but in seconds it will break away from that, too, becoming pure Jet Li and Jackie Chan. Defying age, gravity, and the inevitable hype, they both seem to go into a zone, provoking each other's arsenal, unleashing strikes and counter-strikes as quickly as the other can react. My eye catches Snake, Leopard, Tibetan White Crane, Willow Leaf Palm, some more Mantis?what appears to be the Seeking Leg style?and Eagle Claw.

When the shot is over we play back the sequence on the bank of video monitors. Woo-Ping lets out some cigarette smoke with an enthusiastic cackle. "Tai fai la," he says in Cantonese. "Too fast."

Everyone shares in the mirth, even the Silent Monk and Drunken Master. For continuity's sake we cannot track the tornado of movement that just occurred. After some crew deliberation it is decided that we'll have to slow down the video playback just to follow this fight. Slow down the video? Is that what they said? I have never seen that before?and my last movie happened to be about a race horse.

Like my script's protagonist, I have found myself in the Middle Kingdom, on an unforgettable journey with the legends of martial arts. Like the Traveler, I have to wonder if it's all just a dream.

Journey to the East

Although I've been writing movies for more than 20 years, THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM is my first screenplay inspired by a life-long love for martial arts. I was introduced to Moo Duk Kwan by my late father, a Korean War vet who had learned "a few moves" from a local elder he called Papa-san.

By good fortune, one of my dad's old war buddies had opened a dojang in an abandoned theater in Oakville, Connecticut, and I enrolled when I was 12. A year later Bruce Lee movies would take the US by storm, as would the TV series KUNG FU, and my passion would intensify.

While I embraced Korean karate, my true interest was in Chinese Kung Fu and its inherent philosophy. Nearly excommunicated from my Catholic studies class for carrying the TAO-TE-CHING, I spent hours reading THE MONKEY KING and OUTLAWS OF THE MARSH. These studies were supplemented by Hong Kong triple features at the local drive-in where a long-suffering aunt and uncle of mine nearly lost their minds after hours of poorly-dubbed Golden Harvest features. The drive-in eventually closed down; Bruce Lee's untimely death would break our hearts and shock the world; a high school football injury would knock me out of Moo Duk Kwan. But my martial arts heroes stayed with me, as did their principles.

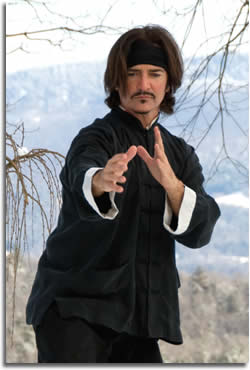

Many years later, after becoming established as a storyteller in Hollywood (might we blame it on those triple features at the drive-in?), I would leave Tinseltown to seek out a quieter life in the woods of northern Vermont. Of all places, that's where I would finally locate the Shaolin Kung Fu I had dreamed of since I was 12.

Word had it that an American practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine had left Boston in the 80's and moved up into the northern mountains. With 30 years of training in Chinese martial arts, Arthur Makaris would eventually open a small, no-frills training center in the same building as his acupuncture/qigong practice. The teachers in his past, I would learn, were some of the most venerable names in kung fu: 33rd generation Shaolin successor Pui Chan, the Taoist monk Kwan Sai-Hung, and Ba Gua Zhang master Dr. Xie Peiqi. In 1999, Sifu Makaris accepted me as a student of Northern Shaolin Praying Mantis.

An irony was that I now had a young son who had discovered my vintage Chinese cinema collection and was taking a "Little Tiger" Tae Kwon Do class with every third kid in the school district. In an effort to introduce to him to the history, mythology, philosophy, and classical literature that informs so much of the traditional martial arts (if you're going to do stick forms, how can you not know about Sun Wukong, the magnificent Monkey King?) I began to read him JOURNEY TO THE WEST and ROMANCE OF THE THREE KINGDOMS at bed time. Of course, as a western kid with a taste for the instant rush of VIRTUAFIGHTER, he found these narratives arcane and often nonsensical. And so I put down the dog-eared classics and began making up a bed time story as something of a primer, a way to pique his interest. I began weaving a hero's journey tale of a young American obsessed by all things Kung Fu who spends his summer days in Boston's Chinatown, rummaging the bootleg DVD shelves of a pawn shop. A troubled kid, dogged and bullied by a Southie gang, he seeks refuge in films like 36 CHAMBERS OF SHAOLIN, FISTS OF FURY, COME DRINK WITH ME, and THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR. But he finds something else in this forlorn shop, something that will alter his destiny and test his mettle.

In the clutter of bric-a-brac and second hand guitars, he is drawn to an antique bo staff, a fighting stick inlaid with gold band and archaic monkey images. By way of Sun Wukong's lost staff the young man is transported to an ancient China of myth and legend, finding himself on a prophesied martial quest: a Journey to the East. In order to fulfill this mission he must return the staff to the immortal Monkey King, imprisoned in Five Elements Mountain for 500 years. But first, he'll need to learn the deeper principles of martial arts and the true meaning of Kung Fu. This, I felt, might fire an iPod kid's interest in the classics and inspire him to look beyond VIRTUAFIGHTER into the deeper precepts of the art.

As this improvised wuxia tale progressed?peopled by martial arts legends, mythological demons, and lethal opponents from warrior folklore?I found my son not falling asleep, but sitting up wanting to know what happens next.

What happened next was it grew into a movie.

When producer Casey Silver asked me who I saw as the two masters, I had only two stars in mind. It only made sense: if this American kid's journey is a kind of Kung Fu OZ informed by his obsession with martial arts cinema, who else could his dream mentors be?

Like Jason Tripitikas (as I named the character after the wandering monk, Tripitika, from JOURNEY TO THE WEST), I would soon be blurring through time zones and landing in China to have tea with Jet Li. The wushu champion had responded well to my screenplay and saw it as a way of "opening up" the Monkey King legend, giving it a fresh spin and sharing it with a global audience. It had been a dream of his since childhood to one day portray China's most-beloved folk hero, and his enthusiasm was infectious. Jet would soon become a creative collaborator, bringing cultural insight to the material as I worked on further drafts. He also told me he could see from the script that either I practiced martial arts or did some research. This, of course, led into a discussion about Shaolin Kung Fu and Yin Fu-style Ba Gua.

"Since I'm finally here in China," I said to him over our final cup of green tea, "I'm hoping to train if possible. Could you recommend anyone in the area who might be willing to work with me?"

Jet sat in calm silence, moving his Buddhist prayer beads through his fingers as he does before answering most questions. "A master?" he asked.

When I nodded, he said in Mandarin, "Go out to the park, early in the morning, and you'll find the best."

"Kowloon Park? Right out here behind the hotel?"

"Yes, go out in the park. Early. You'll find a good master." He smiled and touched his chest near his heart. "Alone, in the park, that's where you'll find the best master for your Kung Fu," he said.

In one of many examples of life imitating fiction during the making of this film, Jet's koan was strikingly similar to the philosophy his character passes on to Jason Tripitikas. But it was also Jet's way of accentuating what he viewed as the core theme of the screenplay: the young hero's quest to free the Monkey King as a metaphor for an internal journey. By freeing the imprisoned sage?the irrepressible "Mind Ape" ?the character is really freeing himself.

Sometimes meeting movie stars is a disappointment, and it can be hard to make even a remote connection to the characters we identify them with. Jet Li is a rare exception; he is as fast and elegant and inscrutable as any of the roles he's played. He is also a deeply spiritual man with a quick, boyish smile who will tell you that the true meaning of martial art is the art of averting conflict.

Days later, I would meet Jackie Chan in Hong Kong and feel the same serendipity. His warmth, comic genius, and bigger-than-life charisma are all key components of Patriarch Lu. Who better to play an allegorical founder of Drunken Boxing than the original Drunken Master?

Sitting at a lavish Chinese dinner hosted by "Big Brother" as the crew calls him, I asked a question about the Choy-Li-Fut system. Jackie exploded into a rapid-fire demonstration of hard and soft styles, describing the differences in few words. His speed and power nearly blew the paper napkins off the table and there was something almost freakish in seeing a man well-past 50 move with better fluidity than any 17 year-old athlete I had ever met.

That's when something daunting strobed through my mind: earlier that day Jackie Chan had threatened to kill me. We had been rehearsing his lines in a hotel room when he realized the cubic measure of English language dialogue he'd have to nail?what would be an unprecedented volume for Jackie Chan. He sank lifelessly into the couch, my pages sliding to the floor. "I can't do this," he said. "I like lines like ?go!' and ?run!' Run is a very good line for me." He then suggested that the impossible task might stress him out and make him kill everyone on the set. He pointed at me and said, "You first."

There is something about Jackie Chan, that even when he threatens your life you feel honored and graciously entertained. Although he urged me to cut down his dialogue (at one point he offered me a bottle of Jackie Chan label Shiraz for every line of dialogue I cut) he would eventually insist on getting some excised lines back in, viewing it as a challenge. He also expressed a true interest in playing the master to a young foreigner. As we discussed the fact that the American actor would have to go from neophyte to trained martial artist in a relatively short time, Jackie looked me in the eye.

"Who will play this kid? Has to be good."

The Kid

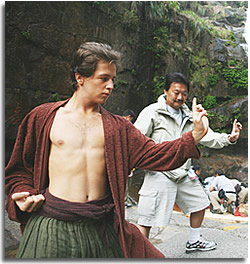

At 5'7" and 135 pounds, Michael Angarano is best known as the shaggy-haired, awkward skateboarder in LORDS OF DOGTOWN. While he didn't even have an introductory kickboxing class on his resume, the 19 year-old actor grew up in the dance studios his mother owns in New York and L.A. He never took her classes, but he was surrounded by movement and choreography and learned to follow along easily. But it was his acclaimed acting skill and kid brother likeability that won him the role over a great many young contenders with black belts.

When I had breakfast with him in L.A., he expressed his excitement about starring in the first movie to pair the reigning kings of Kung Fu. To get into character he had been on a steady diet of Hong Kong film and he was reading everything he could, including back issues of this magazine that I gave to him in a box. All of this, of course, would inform his character at the beginning of the film; how we'd get him to transform into a competent Kung Fu student by the third act was something altogether different. Then again, we had the Master Woo-Ping and his team waiting for him in China.

Bayeh, as the elder is respectfully addressed by those close to him, had prepared Keanu Reeves for THE MATRIX, and he had put Uma Thurman through rigorous training for KILL BILL. With Michael's passion and his touch of daredevil skateboarding skills, I conceded the possibility. But nothing prepared me for what I would find when I met up with the kid two weeks later in sweltering Zhejiang Province.

Bayeh had set up a training center in a modest warehouse at Hengdian World Studios, the movie lot where HERO and a recent host of other Chinese films had been made. When I walked in, I could hear training commands being barked out in Cantonese and the sounds of heavy breathing, feet scuffing on padded mats. As I rounded the corner, I caught sight of Michael launching himself through the air while flowering a bo staff. He landed in a rubbery split that wasn't Shaolin quality, but never the less impressive. The staff wobbled away from him.

"More power," Bayeh said. "Do it again."

Michael looked up at me from the mats. He was sweat-drenched, already thinner after two weeks, but the look in his eye was one of exhilaration: here he was in China, learning wushu from the legendary Yuen Woo-Ping and getting ready to fight on screen with Jet Li and Jackie Chan. The exhilarated look was short-lived; soon, no less than three of Bayeh's young guys?skilled martial artists with names like Money, Tony, and Z?were stretching the American at the same time: one held his legs, one sat on his shoulders, and another held his hands. When the kid finally screamed and said it hurt, Bayeh simply said, "Good."

"I was clueless," the actor admits now with the movie in post-production. "I had no idea of the intensity and what I'd be getting into."

"I was clueless," the actor admits now with the movie in post-production. "I had no idea of the intensity and what I'd be getting into."

Michael acknowledges that the brutal stretching was key to his gaining the flexibility required to learn Shaolin form at an equally brutal pace. "Their philosophy of stretching is entirely different than the philosophy I was familiar with. I was always taught to go slow and always be wary of hurting yourself, especially the erratic movements and bouncing."

He would find Bayeh's approach a far cry from an L.A. Pilates class.

"The philosophy is to jerk and break through your barriers immediately. I swear I heard things snapping and tearing and I was literally screaming. You might limp for two to three weeks, but once you get better you will be more flexible. We started with this every morning in my 8 hour per day?every day?training. Within three weeks, once I was able to walk normally again, I was capable of a full split."

The stretching regimen was followed by training kicks across the floor: front kicks, side kicks, crescent kicks, outside crescent, roundhouse, tornado kicks, and eventually all of the kicks in combinations. When Bayeh picked up on Michael's weak side kick, the actor was made to hammer that individual technique with each leg for an extra half-hour a day.

Kicks were followed by strikes, an hour in horse stance, and then work on the two open hand forms he would learn. Because of the movie's emphasis on the Monkey King weapon, the final two or three hours each day were dedicated to stick training, including the difficult Tai Sing Moon Staff Form from the monkey system.

Angarano says that the experience the character goes through began to parallel his own journey, and he drew on that to maintain the discipline. He was living his role.

After an initial shed of more than five pounds, he would soon pack on eight pounds of ripped muscle. He began to move with fluidity and confidence.

"What do you think?" I asked Bayeh early on.

"Good," the master nodded, encouraged. "Smart."

His assistant Dede, himself a sought-after action director, elaborated in translation: "Bayeh said Michael has good physical intelligence. He catches on fast."

He was also now going airborne in his stick form and landing in effortless full straddle. After three weeks, his spinning back kick was looking dangerously close to polished. I asked Dede how to say "youth is wasted on the young" in Cantonese. When he translated my joke to Bayeh, the elder laughed in a kind of agreement.

Soon the scruffy kid from LORDS OF DOGTOWN would be stick fighting against Jet Li, jumping off tea house roofs with Jackie Chan, and going fist-to-fist against fierce opponents like Collin Chou and the deadly Li BingBing. The experience would amount to a grueling half-year, a challenge that the actor says he could not have handled without Master Woo-Ping and his wushu posse.

"They were the best teachers I've ever known in their kindness and patience. Even though there was a language barrier between us, I feel I bonded with them the most on the film."

Actors usually walk away from a completed movie project with a healthy paycheck and memories mixed between brutal labor and great fun. Sometimes they walk away with the bonus of a cool new skill like skateboarding. But Michael Angarano would leave this project, and China, with something more than that.

"Although I only had a taste of it," he reflected months later, "Kung Fu changes your work ethic and how you think. People are able to do so much more than they believe they are capable of. I also came to realize the tradition that Kung Fu holds and how the true art is passed down from generation to generation. When I was learning a form, I felt part of something greater than I was and I had to respect it and try my best to do it justice."

The Master

It had been thirty years since Jackie Chan had worked with Yuen Woo-Ping.

That long-ago collaboration was the classic DRUNKEN MASTER, an action-comedy that turned the genre on its ear and the stuntman/actor into a super star. Now that three-decade gap was about to be bridged and I found myself at a point where I no longer just wanted to make this movie. I wanted to see it. I said as much to Peter Pau as we all sat around a long conference table with Woo-Ping, reading through the martial arts scenes in my screenplay and discussing the staging. The Master's translator began reading one of my detailed passages in which "the Silent Monk parries and intercepts a Phoenix Eye Fist, trapping it in a lightning-quick gou; as his opponent withdraws, he grips tight and catches a free ride, monkey-stepping his way into a tumble from which he executes a reverse crane sweep?known in Henan province as the iron broom."

Bayeh glanced at me out the corner of his eye, quietly working a toothpick behind his closed lips. The translator read on, describing an exchange of styles and strategy. The Master sat back in his chair and studied me.

"John," he said in a rare go at English. "You were at the training center yesterday. The boys told me. Doing old Shaolin."

I sat like the proverbial deer in the high beams.

"Not too many westerners do old Shaolin Tanglangquan," he said, referencing the Praying Mantis system. Then he returned to the script pages and spoke Cantonese. His translator eyed me now: "He says that when most scriptwriters get to a martial arts scene they just write ??and now they fight.'"

Quiet laughter ringed the table, everyone looking my way.

One of the cardinal sins in screenwriting is putting camera angles and detailed shots in the narrative, a sin called "directing on the page." Fortunately, I always knew better. But now, here I was, possibly guilty of choreographing martial arts on the page, and in the presence of one of the most successful and influential action directors in the history of Hong Kong cinema, the man who probably had the most subconscious influence on me writing this script in the first place. I felt like a nightclub hoofer showing a written dance routine to Fred Astaire.

"Please explain to the Master," I said. "It's just an interpretation. Some of it relates to character and story, but it's mostly for timing and metrical effect for the reader."

The Caucasian translator ignored me. But Bayeh did not. He began to go down the list of characters, asking me which weapon I envisioned each individual employing. I was grateful and ready, naming the Crescent Moon Dao for the evil Jade Warlord, butterfly knives and darts for Golden Sparrow (a character influenced by King Hu's classic COME DRINK WITH ME), and on down the line from monk cudgels to deer hook swords. Bayeh casually penciled a few notes in the script and then we moved onward, discussing the settings of certain fights and how to incorporate props and surroundings. Knowing both stars' unique talents so intimately, he was brimming with ideas on how to take advantage of Jackie's humor or Jet's palpable internal power.

"There should be three levels of martial arts style in this film," Bayeh advised me. The first level should be classical kung fu; the fighting arts of ancient China performed at the supreme level that Jet's and Jackie's characters would have achieved. The second level would be "supernatural martial art," where fighting skill transcends even the supreme level. Only a few of the characters in the film would fight at this level as dictated by their respective mythologies. Li BingBing's interpretation of the Bride with the White Hair would be one; Collin Chou's Jade Warlord another. And, of course, the immortal Monkey King. The third level would be straight-up street fighting?economy of movement, no flowery fists. Like an inspired composer, Woo-Ping knew when and where these three approaches would set the action tone, play counter-point, and even intersect in some of the more electric fight stanzas.

"There should be three levels of martial arts style in this film," Bayeh advised me. The first level should be classical kung fu; the fighting arts of ancient China performed at the supreme level that Jet's and Jackie's characters would have achieved. The second level would be "supernatural martial art," where fighting skill transcends even the supreme level. Only a few of the characters in the film would fight at this level as dictated by their respective mythologies. Li BingBing's interpretation of the Bride with the White Hair would be one; Collin Chou's Jade Warlord another. And, of course, the immortal Monkey King. The third level would be straight-up street fighting?economy of movement, no flowery fists. Like an inspired composer, Woo-Ping knew when and where these three approaches would set the action tone, play counter-point, and even intersect in some of the more electric fight stanzas.

The fact that Bayeh referred to components of my scripted combat, especially in the J and J fight, is to say that he used them merely as a jumping-off point. While some of the fighting styles that I designated for the characters were essential to the story (Monkey Kung Fu for Sun Wukong, Drunken Fist for Lu-Yan), Bayeh assigned signature martial systems to others (Phoenix Dancing in Ninth Heaven for the villain Ni-Chang is one example).

In some instances it was true collaboration, as in the case of a training sequence in which Jason is practicing horse stance in the Wuyi Mountains. In the script, Jet intervenes with Jackie's training methods and conflict erupts. All the while, the kid suffers through a deep ma bu, and even gets swept off his feet a few times by an unimpressed Jet.

Bayeh took this scene apart then reassembled it on the mats of the training center using young Michael, and his stunt guys as Jet and Jackie stand-ins. Bayeh wanted to transplant one of my earlier ideas in which Jet and Jackie go toe-to-toe in dueling Shaolin Five Animals, and work it into the training sequence as the two masters debate which style the young wanderer is right for. As I stood off watching, Bayeh coached his players through the rehearsal. The kung fu conductor gestured and shouted direction?at times laughing with excitement?as he made the scene build to a perfectly-timed crescendo. "Okay?" he asked.

I headed off to my laptop to nail down a version of what the Master had just riffed on from one of my earlier renditions. This kind of exciting interplay would continue throughout pre-production, transcending the grind of movie making and becoming a unique martial arts experience. I would learn a lot about technique, timing, and footwork through this interplay; even in choreographed sequences that were "movie kung fu" or sport wushu, there was something to be absorbed about good line, using the eyes as a weapon, and?to paraphrase Duke Ellington?"it don't mean a thing if it ain't got fa jing." Bayeh's "more pow-ah!" became a litany on set.

Over time, I tried to pick up certain subtleties of drunken feints from Jackie's Eight Immortals set, working some nuance into one of the Shaolin forms I currently practice. From Jet, I was reminded about the importance of zazen, of seated meditation, and focusing inwardly to develop awareness and self-expression in martial art. His audacious portrayal of the Monkey King is testament to that philosophy. In discussing Monkey Kung Fu and the signature style for the simian folk hero, Jet once said "Monkey King's style is not external. It comes from the heart. The heart leads the style."

It was heart, also, that would lead young Michael Angarano.

Watching the growth of the displaced Traveler?this pizza-eating Mets fan from Brooklyn?I was reminded that remarkable things can be achieved once an individual makes a steadfast and passionate commitment to a goal. Youth might be squandered on the young, but we would've been screwed without it.

101 Days of Kung Fu

During my final day on the set, I watched an ambitious fight scene in a plum blossom orchard in Fang Yan: young Michael wielding his staff against attacking soldiers, Jet Li using his sash as a weapon on the left, Jackie Chan doing Hung Gar to his right. While Bayeh, his ever-present Zhong Nan Hai brand cigarette in hand, directed the action from behind a small monitor, Peter Pau was capturing it all on film from inside his blackened, off-limits camera tent.

The life-imitating-art-imitating-life paradigm came to mind again: if this story is really an inward journey, a self-discovery quest for a young man who has found talismans in the canon of martial arts cinema, it had all been perfectly cast. The character would want Jet and Jackie, like Yin and Yang, to mentor him through his nightmares and prepare him for his trials; he'd want the legendary Woo-Ping to direct the epic battles; he'd want Master Pau, the man who can turn bamboo blue at magic hour, to provide the Zen composition and capture the dream before it faded.

And there was someone else standing on set that day: my son, now 13. He was wearing a "J and J" ballcap that Jackie had given to him along with other gifts to commemorate the filming. He was still smiling from the handshake Jet Li had just offered down from horseback. Here he was, watching characters and battles that were born by his night lamp four years earlier, like a warrior tale told by a fire. When the last shot was done, he and I walked alone up the ancient village road back to base camp. In a few days we'd be leaving China, time travelers headed home.

"Hard to believe, isn't it?" I said, "How this all happened. How do you feel, knowing that a story your old man made up for you has turned into a movie like this?"

"I was thinking," he said, looking over his shoulder as if he wanted to stay until the last cable was packed away. "If the Monkey King is freed, that's when the journey really begins. This movie is like a prequel to JOURNEY TO THE WEST. The Monkey King helps the Tang Monk travel to India to find the scriptures, and they have to get past dragons and those flesh-eaters and then Jet would get to fight that prince with six arms. A lot of CGI. That'd be sweet."

My boy was now far beyond bedtime stories; he was talking sequel. But he was also talking the classics, and that was kind of the goal long ago. Perhaps it is still the goal: ignite the interest of a new generation of western filmgoers. Maybe inspire them to investigate the classical source and to remember that?in this era of MMA and VIRTUAFIGHTER?deeper precepts and a code of virtue remain as the true foundation of Kung Fu.

Hoofbeats came out of the dust. Jet Li trotted up the dirt road on his white horse, robes draping his saddle. He stopped a distance away, waved his arm and sent us off with a beaming smile. "Goodbye, my friend!"

| Discuss this article online | |

| FORBIDDEN KINGDOM: the movie |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2008 .

About

John Fusco :

John Fusco is the writer of ten movies and a novel. He studies Northern Shaolin Praying Mantis at the Vermont Kung Fu Academy, and has studied Yang Si Taiji under Sifu ChenGuo Yi in Zhejiang Province, China. Proceeds from this article have been donated directly to Jet Li's One Foundation.

www.one-foundation.org

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article