By Gene Ching

In October 2009, at the 11th National Games of the People's Republic of China,

Champion Zhao Qingjian did the unimaginable. He won. Of course, any athlete who qualified for the games had a shot. But for Zhao, it was such a long shot.

Nicknamed the Chinese Olympics, the National Games (全国十一运会预赛) is the premiere sports event in China. It is held every four years and pits province against province in a fierce fight for glory, all in the name of hometown pride. At the 11th Games, over ten thousand athletes battled over 551 gold medals, each hoping to bring one back home to their province. A gold medal from the National Games is one of the most coveted decorations a Chinese champion can earn. Wushu, as a national pastime and cultural treasure, is the only one of the thirty sports of the National Games that has true Chinese roots. It is a showcase event.

In October 2009, at the 11th National Games of the People's Republic of China,

Champion Zhao Qingjian did the unimaginable. He won. Of course, any athlete who qualified for the games had a shot. But for Zhao, it was such a long shot.

Nicknamed the Chinese Olympics, the National Games (全国十一运会预赛) is the premiere sports event in China. It is held every four years and pits province against province in a fierce fight for glory, all in the name of hometown pride. At the 11th Games, over ten thousand athletes battled over 551 gold medals, each hoping to bring one back home to their province. A gold medal from the National Games is one of the most coveted decorations a Chinese champion can earn. Wushu, as a national pastime and cultural treasure, is the only one of the thirty sports of the National Games that has true Chinese roots. It is a showcase event.

Zhao was a dark horse because of his age. When he entered the National Games, he was already thirty-one. That might not seem too old for kung fu, but it is well outside the window for top-level wushu competitors. Male wushu athletes don't even compete at that level past their twenties, much less win. What's more, Zhao won gold in changquan (long fist 長拳). As the principal empty-hand routine of modern wushu, that's the most competitive ring. And with the present rules of the sport, which emphasize difficult gymnastic techniques called nandu (難度), changquan is extremely demanding on any athlete's body. With his unprecedented victory, Zhao struck a blow for traditional kung fu, deep in the heart of the modern wushu arena.

The Rugged Grains of Shaolin Soil

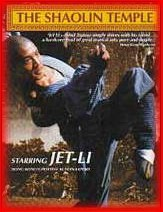

Despite his accolades, Zhao's genuine smile and sparkling eyes betray his country roots. "My dad said to always treat people with heart," says Zhao in Mandarin. "Always smile and they will smile back." Zhao's father practiced Shaolin kung fu. They lived in a small farming community in Dongping in Shandong Province, where martial arts were scarce. As a child, Zhao began training in Shaolin style under one of his dad's younger kung fu brothers. It was Jet Li's debut film, The Shaolin Temple that got Zhao interested in wushu.

The film was released in 1982 but it didn't make it out to Dongping until nearly half a decade later. Zhao didn't understand what wushu was back then, but like for many champions of his generation, that film made him want to try it. In the wake of that film, over 100 kids signed up for wushu classes; however, Dongping didn't have adequate training facilities. The kids trained in the dirt, which was too uneven to practice nandu techniques. Many kids were injured. Many others dropped out just because they couldn't stand the rigorous leg stretching. Soon Zhao was the only student left.

The film was released in 1982 but it didn't make it out to Dongping until nearly half a decade later. Zhao didn't understand what wushu was back then, but like for many champions of his generation, that film made him want to try it. In the wake of that film, over 100 kids signed up for wushu classes; however, Dongping didn't have adequate training facilities. The kids trained in the dirt, which was too uneven to practice nandu techniques. Many kids were injured. Many others dropped out just because they couldn't stand the rigorous leg stretching. Soon Zhao was the only student left.

Zhao tried to give up too, feigning a stomach ache. But his teacher wasn't fooled. Seeing Zhao's potential, the teacher went to Zhao's dad, who wasn't fooled either. Zhao had been a sickly child before wushu practice fortified him. Later, an aerial accident hospitalized him for two weeks. It was Zhao's first serious injury, but it didn't stop him from his fate. Undaunted, he forged onward, and eventually won the title of All-Around Champion at the Dongping County tournament called the Hope Cup (希望杯). However, that victory came too early. Zhao was too young to progress to the provincial team, so he hit a plateau. With nowhere else to go, Zhao went south.

Shanwei in Guangdong Province had just been approved as a city by the Chinese government. When a region reaches a certain population, it can apply for city status. To improve their notoriety, Shanwei was scouting for wushu athletes for their newly-founded municipal team. Athletes were offered living and board, plus a small stipend if they made the team. Zhao qualified and signed a contract, and his parents helped him out with additional financial support to get him there. So at the tender age of 12, Zhao set off on his own, journeying over 1100 miles to pursue his martial dream.

Unfortunately, things didn't work out. As a new city, Shanwei was still poor. The living conditions were meager. The promised fare was limited to one meal a day. The city was much poorer than where many of Zhao's colleagues ended up, and when friends from Shandong visited, he was embarrassed. Yet Zhao was bound by his contract, and he stayed there for three years. He only called home once during that time. He didn't compete that much for Shandong, but did manage to win the Guandong Province Wushu Championships for dao (single-edged sword 刀) and staff.

When the term limit finally ran out, Zhao returned home to Shandong. Shanwei had been a disappointment, so his intent was to stay in Shandong. However, a martial brother, Xu Dezheng, changed Zhao's mind. Xu was also from Shandong, part of a group of Shandong masters including Chen Fei and Ben Zhang who wound up studying at Shaolin. They comprised the third wave of Shaolin immigrants to America. All but Zhao wound up settling in California's Silicon Valley. Xu had studied at Shaolin Temple and was then holding a teaching position at Wuhan Sports College. Xu saw Zhao's potential and advised him to go to Shaolin. So at 15, Zhao left home again. Shaolin was closer to home, less than 300 miles away.

Through Xu's connections, Zhao was introduced to the Warrior Monk Demonstration Troupe at the illustrious Shaolin Wushuguan. Zhao's skill was remarkably high, so he was immediately drafted. As soon as he arrived, they shaved his head and got him to perform for tourists. Zhao remembers seeing the head coach nodding approvingly after his first performance with the troupe.

Zhao ended up staying at Shaolin for three years. As a member of the Shaolin demo team, he took the name Shi Xingjian and was under the direct tutelage of Shi Deyang. He had to learn the eighteen weapons, an allusion to the vast arsenal of cold arms that the Shaolin warrior monks must study. Zhao specialized in dao, staff, three-section staff and nine-section whip. He shared a room with Shi Deshan (currently in Houston, TX) and became close friends with his kung fu brothers: Ye Xinglie (Shi Xinglie, currently in San Jose, CA) and Shi Xingwei (currently in Las Vegas, NV). The troupe toured the world. Zhao demonstrated in Austria, Belgium, Belize, Denmark, Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Malaysia, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States, nearly two dozen countries overall.

Zhao was often asked to teach at workshops following those performances, but back then, he wasn't comfortable in that role. He felt his martial theory was still too weak to be teaching. After the 1998 American tour of America, four members of the Wushuguan troupe stayed to teach: Deshan, Xinghao, Xingying and Yanfeng. Zhao could have stayed too. He remembers contemplating that possibility at the end of the tour in Los Angeles. Zhao spent the night discussing his options with his kung fu brothers. Although America offered a lot of promise, Zhao still lacked confidence in his teaching skills, so he chose to return to China and go back to school.

The Dao of Wushu

As Zhao was reaching adulthood, he already had over a decade of hardcore martial arts training under his belt, but he felt he had never really tested himself in competition. Of his generation of Shaolin brothers at the Wushuguan, only Zhao and Xingwei remained. All the others had moved on. Zhao felt it was time to leave too, so he applied at the Wuhan Sports College. He tried to get Xingwei to come with him, but Xingwei didn't feel that his academic background was strong enough to get in. Zhao had his doubts too. Outside martial arts schools, Zhao had no formal education. He had taught himself to read while he was in Guangdong, but he did that by studying martial arts pulp fiction novels, or wuxia xiaoshu (武俠小說). That was a far cry from what is required to get into college. In China, college entrance exams are very competitive. Zhao had to pass a rigorous written exam, along with a technical exam.

Once again, his skills carried him. Zhao was very worried about the written, but just like at the Shaolin Wushuguan, he caught another head coach's eye during the technical exam. Zhao was pulled aside and told he could get in. The director of the sports department, Mei Hanchao, arranged a scholarship for Zhao so he could afford tuition, cutting the 20,000 fee into a fourth. After he was accepted, Zhao returned home again and showed his proud father his admission papers. Zhao was the first person in his family to go to college.

During Zhao's sophomore year, he caught the eye of another coach at a national tournament. Wu Bin, head coach of the illustrious Beijing Wushu Team and tutor of Jet Li, was the leading force in wushu at that time. Few members of the Beijing Wushu Team were actually from Beijing. Most were drafted. After Wu spotted Zhao, he drafted him immediately. Zhao was the first competitor from Wuhan to make it to the national level and the first to be drafted to the Beijing Wushu Team. However, Zhao didn't make much of it back then. He was just starting in wushu, so at the time he barely realized the significance.

Wu Bin's coaching would be a major turning point for Zhao. Under Wu's direction, Zhao captured an impressive string of medals in national and international competitions. His winning streak began in 2000 at the National Wushu Taolu Championships (全国武术套路锦标赛). Zhao won gold in changquan and dao, as well as bronze in staff. That amazing showing earned Zhao the All Around Men's Champion title too. "That was very surprising," Zhao now admits.

The following year would be the 9th National Games, and it was to be Wu Bin's last before retiring. Disappointingly, the Beijing Wushu Team had a poor showing. The team won five gold medals in the preliminaries (one was for Zhao's changquan), but only Liu Qinghua managed to win gold in the finals. "I still feel sorry to Wu Bin because it was his last year," say Zhao. "Wu Bin really taught with all his heart. Success came too fast for me. It was too much pressure to hold on to the title."

Despite his rigorous training schedule, Zhao still managed to graduate from Wuhan Sports College. The year following graduation, he came back strong. At the 7th World Wushu Championships in Macao, Zhao brought home gold medals for both changquan and duilian (literally "facing drill" or "opposed practice," which are multi-person forms對練). In 2005, he garnered another gold for changquan at the 10th National Wushu Taolu Championships. That same year, Zhao took golds in dao, staff and All Around at the 4th East Asian Games. At the 9th World Wushu Championships in 2007 in Beijing, Zhao won gold again, this time for broadsword. That set him up nicely for the Wushu Tournament Beijing, held during the 2008 Olympic Games.

"Forty wushu athletes were pre-selected for the Olympic team in 2006," reveals Zhao. "Seven were chosen during the 2007 World Wushu Championships. Only six made it to the Wushu Tournament Beijing. I won a gold medal for dao gun (staff棍) combined. Those didn't require hard nandu. The pressure on my mind was extremely high because it was Olympic. I could only compete there once in my lifetime."

The Dark Horse

After the Wushu Tournament Beijing, Zhao was completely exhausted. His age was catching up to him so he took the longest training break of his life – two months off. His body just couldn't recover anymore. The Beijing Wushu Team coaches nearly gave up on him. However, the team didn't have many stars at that time so he was committed to the Nationals.

In April 2009, a week before the preliminaries, Zhao's nandu felt very unstable. Nevertheless, he managed to secure the gold in changquan at those preliminaries, but it cost him dearly. He spent all his energy and threw up after competing, with his dao and staff events still to come. He managed to rally somewhat for his dao event, placing sixth. But after that he was so exhausted that he couldn't eat and passed out. The team doctor examined him. Zhao had a fever of 99.86°. He still had to finish his events and rallied once again, managing to get silver in staff. Zhao confesses that he was so out of it "I didn't even know what I was doing."

The National Games were held in Zhao's home province of Shandong in October 2009. A few days before the event, Zhao felt his energy was up. In the finals, Zhao's changquan was almost perfect with a score of 9.82. He secured the gold medal, just beating out his nephew, Yuan Xiaochao of Shaanxi Province, who was only 0.01 points behind. Zhao also placed fourth in dao. "I don't really know how the finals went," say Zhao. "I used some music for warm up. I don't think. My mind is quiet. I don't draw many conclusions when I succeed. I only analyze when I lose."

As to the secret of Zhao's longevity, he says it's all about happy wushu. "You have to like it. If you are only in it for the gold, forget it. Wushu is my life. Wushu is my only entertainment. You can practice wushu for health, for competition, for so many reasons. If I'm promoting wushu, I want to bring happiness, not hardship. Beijing is too rich. The kids can't tolerate hardship. When I teach, first I have to get them interested. Once they're interested, that brings happiness."

Sometimes, Zhao dreams of competing again. "If they asked me, I'd jump into the ring again," he says. "But they won't ask me. It's too cruel at my age. Maybe I'll compete again in traditional."

| Discuss this article online | |

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine January/February 2011 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2011 .

Written by Gene Ching for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article