Well here we go again. Another A-list actor who has been touted by the studios as doing all of his own stunts and fights in a martial art oriented film, claiming that the actor has, in conflicting reports, undergone anywhere from six to eight months to up to a year of intense samurai sword and martial art training. I'm of course talking about Tom Cruise in his latest epic THE LAST SAMURAI. But in support of the film, I won't mention anything about his Japanese stunt double or his American stunt double that were "not" involved in the fights because Tom was doing everything himself. What also adds to the benevolent "mysticism" of the whole thing, is that Tom has not made himself available to anybody from the martial art press. Perhaps we would ask too many of the wrong, or in our reader's eyes, the right questions.

Well here we go again. Another A-list actor who has been touted by the studios as doing all of his own stunts and fights in a martial art oriented film, claiming that the actor has, in conflicting reports, undergone anywhere from six to eight months to up to a year of intense samurai sword and martial art training. I'm of course talking about Tom Cruise in his latest epic THE LAST SAMURAI. But in support of the film, I won't mention anything about his Japanese stunt double or his American stunt double that were "not" involved in the fights because Tom was doing everything himself. What also adds to the benevolent "mysticism" of the whole thing, is that Tom has not made himself available to anybody from the martial art press. Perhaps we would ask too many of the wrong, or in our reader's eyes, the right questions.

According to the film's screenwriter, Marshall Herskovitz, Cruise worked several hours every day for about a year with a dedication and a discipline that was totally Samurai, assuming that Herskovitz knows what that is supposed to mean. In a Warner Brothers press release, Cruise is quoted as saying, "I worked for eight months to get in shape for this picture. I learned kendo, Japanese martial arts, all manner of weapons handling. I not only had to ride a horse, but I had to effectively fight while riding. I studied Japanese. As far as training goes, you name it, I've done it. Several nights of double-sword fighting against multiple opponents, five days and one night of fending off murderous Ninja intruders, weeks of martial arts drills opposite my Japanese co-stars and finally two months of relentless battle sequences.

"Initially I was concerned about achieving realism in the fight scenes, but I focused on flexibility and gradually lowered my center of gravity with daily workouts enabling to execute naturally fluid moves without stiffness. I developed deeper breathing and got a clearer sense of awareness, of mind over body, which helped me get trough some of the more intense battle scenes without injury."

However, if anyone of you have seen the interviews featured on those network TV, "Behind the scenes" types of shows, like ET TONIGHT and INSIDE HOLLYWOOD, Tom proudly says how he loves Kurosawa films and that he thought everyone worked hard to make this the best samurai film ever made, amidst videotaped shots of Tom doing a samurai sword fight sequence. To the untrained eyes of the fluff and flummery of these overly made-up, perfectly combed hair-doed interviewers, I'm sure the fights look impressive. However, to any decent martial artist, the fights look like something a few guys at the local martial art school could do on any weekend at some parking lot, filmed by someone who borrowed his friend's digital camera. That doesn't mean they're bad, they're just not worth $90-100 million.

But before the final verdict is in, watch the film and observe how the fights scenes were shot and edited. If it's a lot of tight shots with spinning and loud sound effects, not good. If it's a lot of wide angle shots of sword action, where you can't make out who the fighter is, yet on inserted close-ups, you can clearly see it's Tom, not good. But if it's wide angle shots where you can plainly see Tom's face spinning, slicing and dicing, then you know the stunt doubles that don't exist, weren't used. But regardless, the film does sound interesting.

But before the final verdict is in, watch the film and observe how the fights scenes were shot and edited. If it's a lot of tight shots with spinning and loud sound effects, not good. If it's a lot of wide angle shots of sword action, where you can't make out who the fighter is, yet on inserted close-ups, you can clearly see it's Tom, not good. But if it's wide angle shots where you can plainly see Tom's face spinning, slicing and dicing, then you know the stunt doubles that don't exist, weren't used. But regardless, the film does sound interesting.

Set in Japan during the 1870s, THE LAST SAMURAI tells the story of Capt. Nathan Algren (Cruise), an American military officer hired by the Emperor of Japan to train the country's first army in the art of modern warfare. As the government attempts to eradicate the ancient samurai warrior class in preparation for more Westernized and trade-friendly policies, Algren finds himself unexpectedly affected by his encounters with other samurai, led by Katsumoto (Ken Watanabe), which places him at the center of a struggle between two eras and two worlds, with only his sense of honor to guide him.

For director Edward Zwick, THE LAST SAMURAI was the realization of a lifelong dream. Zwick has long been fascinated by Japanese culture and Japanese films. In a sense, he has been imagining THE LAST SAMURAI since he was a teenager.

"I first saw Akira Kurosawa's THE SEVEN SAMURAI when I was 17 and since then I've seen it more times than I can remember," he admits. "In that single film there is everything a director needs to learn about storytelling, about the development of character, about shooting action, about dramatizing a theme. After seeing it, I set out to study every one of his films. Although I couldn't know it at the time, it set me on the course of becoming a filmmaker."

A long time student of Japanese history, Zwick developed an intense interest in the time period known as the Meiji Restoration. The end of the rule by the old Shogunate led to Japan's first significant encounter with the West after a self-imposed isolation of 200 years. "And most of all," he adds, "it was a time of transition. In every culture, that moment of change from the antique to the modern is especially poignant and dramatic. It is also wondrously visual. Each image, each landscape, each room tells the story, the juxtaposition of the old and new. A man in a bowler hat strolls beside a woman wearing a kimono. A man firing a repeating rifle faces a man wielding a sword."

Zwick's films have often explored the complexities of war and honor like in GLORY and LEGENDS OF THE FALL. To dramatize the differences as well as the common ground between a Western soldier and a samurai warrior were irresistible. "First in college and then for years after, I read a great deal of Japanese history," Zwick tells. "I was deeply moved by Ivan Morris's "The Nobility of Failure," which tells the story of Saigo Takamori, one of Japan's most famous figures, who first helped create and then rebelled against the new government. His beautiful and tragic life became the point of departure for our fictional tale."

The change from feudal Japan to a more modern society meant the demise of certain "archaic" customs and values epitomized by the samurai. For many years, they held a highly respected place in the social order. Like England's knights, samurai soldiers protected the lords, or, in this case, the Shogunate, to which they had sworn fealty. As the knights upheld their system of chivalry, the samurai lived by a code called Bushido, "the way of the warrior," which emphasized, among other things, loyalty, courage, fortitude and sacrifice.

The change from feudal Japan to a more modern society meant the demise of certain "archaic" customs and values epitomized by the samurai. For many years, they held a highly respected place in the social order. Like England's knights, samurai soldiers protected the lords, or, in this case, the Shogunate, to which they had sworn fealty. As the knights upheld their system of chivalry, the samurai lived by a code called Bushido, "the way of the warrior," which emphasized, among other things, loyalty, courage, fortitude and sacrifice.

In contrast to the modern weapons the West now offered Japan, the samurai seemed anachronistic to the proponents of progress. This new lust for all things modern left no room for the Samurai with their fabled swords and old-fashioned notions of honor, exemplified here by their last remaining leader, Katsumoto (Ken Watanabe) and his few devoted warriors. Katsumoto's challenge is to maintain his personal principles in a society that no longer values them. His struggle, especially in combination with Algren's own reluctant spiritual journey, appealed to Zwick.

"I've always found the core values of the Samurai culture to be both admirable and relevant," he relates, "in particular, the understanding that violence and compassion exist side by side and that poetry, beauty and art are as much a part of a warrior's training as swordsmanship or physical strength. Also, I'm interested in the unexpected possibility of spiritual rebirth reaching those lives for whom it seemed the least possible."

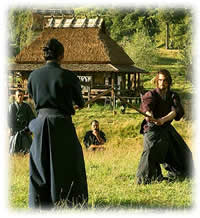

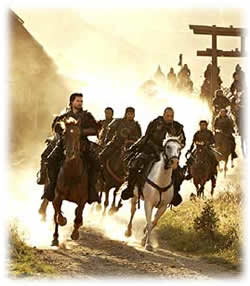

New Plymouth, New Zealand, was determined to be the best locale in which to replicate certain 19th century Japanese vistas especially for the battle sequences. In the search for extras to appear as Katsumoto's loyal Samurai, the casting department found 75 Japanese residents of Auckland, a five-hour drive from New Plymouth. Additionally, stunt coordinator Nick Powell (GLADIATOR, BRAVEHEART) hand-picked a group of novice Japanese actors to become his "core" Samurai. None were professional stunt men and only two could ride horses, but all were athletic and enthusiastic. After two weeks of rigorous training, they proved their mettle, shooting arrows and participating in complicated kendo drills like experts and, in one particularly impressive display, riding horses at high speed down a hill while firing arrows with no hands on the reins.

The production next staffed the Japanese Imperial Army by finding some 600 extras in Japan and putting them through boot-camp to become a credible military force. They learned to march and drill, to handle and fire a rifle, to lunge, parry and thrust a sword, to work with a bow and arrow, and to manage "movie" hand-to-hand combat.

Zwick shares, "What we happily discovered was that so many of the extras we found already had some martial arts training and were eager to demonstrate those skills. It's been awhile since Japanese-style fighting has been on the screen. The Chinese martial arts have had exposure in a lot of popular movies in recent years, and even in the kinds of wire work that has inspired, but the disciplines practiced traditionally in Japan have their own brilliance. In a way, many of the actors saw themselves as ambassadors, able to showcase this style to a worldwide audience. They were excited to be part of this, and we were immensely grateful to have them."

Production took on the shape of a military event. The storyboards for what were known as the fog battle and the final battle became detailed, strategic battle plans. "Both the fog and final battles were about strategy and ingenuity," says Zwick. "Any filmmaker approaching these kinds of sequences should study Kurosawa and in fact, I watched RAN again prior to filming GLORY. But, ultimately, our battles are unique to this movie and specifically driven by the situations facing the Samurai and the Imperial Army. We had to consider how traditional warriors like the Samurai with no firearms would attempt to defeat a modern force with modern weapons."

As Zwick points out, when the samurai appear out of a mist-shrouded forest, descending upon the ill-prepared Imperial Army like ghostly demons, "the idea was that the samurai would use the cover of fog for surprise, allowing them to attack swiftly and suddenly, at their discretion. There is also the psychological advantage of using the forest and the fog as cover, so that when they chose their moment to strike they would materialize as if out of nowhere, in their terrifying, ancient armor, with their legendary, lethal swords."

As Zwick points out, when the samurai appear out of a mist-shrouded forest, descending upon the ill-prepared Imperial Army like ghostly demons, "the idea was that the samurai would use the cover of fog for surprise, allowing them to attack swiftly and suddenly, at their discretion. There is also the psychological advantage of using the forest and the fog as cover, so that when they chose their moment to strike they would materialize as if out of nowhere, in their terrifying, ancient armor, with their legendary, lethal swords."

Zwick based this tactic and those he employed in the final battle on several historical sources, including that of famed samurai master and martial arts teacher Miyamoto Musashi, who is credited with inventing and perfecting the technique of fighting with two swords and wrote "The Book of Five Rings," a spiritual and technical manual printed in 1645.

Surveying his battlefield for the first time, Zwick was momentarily awed. "It's one thing to plan and imagine what you want on a film, but when you actually arrive and survey the scene there's a moment of 'Oh my God, what was I thinking?!' In truth, if we had not done as much preparation in the earlier stages we would never have been able to make this movie because there, in the thick of it, we had so little time to talk with 700 men storming over a hill and explosions going off."

Supplying the action was a monumental weapons inventory, comprised of both traditional samurai blades and arrows and circa 1800s firearms, meticulously restored by the production. Zwick was also anal about the proper usage of various kinds of swords, which was quite specific down to the way in which scabbards were tied and how a certain blade would be worn differently in battle or on the street. Several high quality swords were purchased from renowned swordsmiths in Japan as samples for pieces made for the film, as well as faux blades from the renowned Kozu prop house in Kyoto and from Shogiko Studios, the movie company famous for its samurai films.

"It seems to me that every movie has its own particular language and it usually evolves in the course of filming. It is at times a celebration of yin and yang and that manifests itself in images and movement," offers Zwick, "as in the scene where Taka dresses Algren for battle Algren, the warrior, for once is passive while she does this but she ends up kneeling in front of him in a traditional pose of submission. It is a love scene, there are definite sexual undertones, but not in the typical way. The kneeling position is also associated with prayer. In another scene Katsumoto, the quintessential samurai, appears prostrate in front of the Emperor. There is a ritual, almost loving way a sword is handled; the kendo drill, a martial exercise, is also a graceful dance. All these peaceful expressions of respect and dedication arise in a film also about violence and death. There is a lot of duality, as there is in the Japanese culture. These recurrent movements and ideas become the film language; I don't plan them necessarily, they happen naturally."

"It seems to me that every movie has its own particular language and it usually evolves in the course of filming. It is at times a celebration of yin and yang and that manifests itself in images and movement," offers Zwick, "as in the scene where Taka dresses Algren for battle Algren, the warrior, for once is passive while she does this but she ends up kneeling in front of him in a traditional pose of submission. It is a love scene, there are definite sexual undertones, but not in the typical way. The kneeling position is also associated with prayer. In another scene Katsumoto, the quintessential samurai, appears prostrate in front of the Emperor. There is a ritual, almost loving way a sword is handled; the kendo drill, a martial exercise, is also a graceful dance. All these peaceful expressions of respect and dedication arise in a film also about violence and death. There is a lot of duality, as there is in the Japanese culture. These recurrent movements and ideas become the film language; I don't plan them necessarily, they happen naturally."

Not unlike the tenet of Taoism, you don't find the "way," the "way" finds you.

About

Dr. Craig Reid :

![]() Written by Dr. Craig Reid for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

Written by Dr. Craig Reid for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article