The Jingwu Association was China's first modern martial arts academy. Though martial arts was not the only thing in its program, Jingwu's enduring legacy is its martial arts. In 1919, to celebrate its 10 year anniversary, the Jingwu Association released a book that shows in pictures and words its achievements through its first decade. One section of that book is devoted to what the Jingwu Association refers to as its "wushu" program. Though the Chinese word "wushu" has come to be closely associated with the performance sport developed by the Chinese in the 1960s, it actually means "martial arts," which is the meaning intended by the Jingwu Association.

The Jingwu Association was China's first modern martial arts academy. Though martial arts was not the only thing in its program, Jingwu's enduring legacy is its martial arts. In 1919, to celebrate its 10 year anniversary, the Jingwu Association released a book that shows in pictures and words its achievements through its first decade. One section of that book is devoted to what the Jingwu Association refers to as its "wushu" program. Though the Chinese word "wushu" has come to be closely associated with the performance sport developed by the Chinese in the 1960s, it actually means "martial arts," which is the meaning intended by the Jingwu Association.

Jingwu Northern Shaolin

The Jingwu's "wushu" curriculum was largely based on Northern Shaolin. By definition, a Northern Shaolin system or routine is one developed in the Northern Shaolin Temple (located in Henan Province) or derived from systems/routines coming from there. The routines are normally performed along a straight line running from left to right and back and forth, focus on expansive moves with the limbs extended out to their full length, and place more emphasis on leg techniques - such as sweeps, kicks, jumps - than on hand techniques.

Two comments about this classification: first, the whole issue of the historical authenticity of the Shaolin Temple and whether there was one or more Shaolin Temples is very much an open question; second, the Northern vs. Southern Shaolin classification scheme has many exceptions. It should also be noted that what is called Northern Shaolin is often referred to in older Chinese works (including the Jingwu Anniversary book) as "boxing from the Yellow River," the Yellow River being the major river in Northern China.

The Patron of Jingwu Martial Arts: Huo Yuanjia

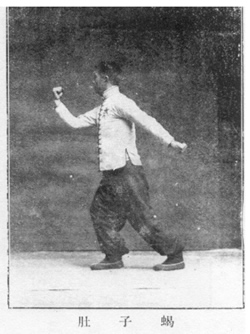

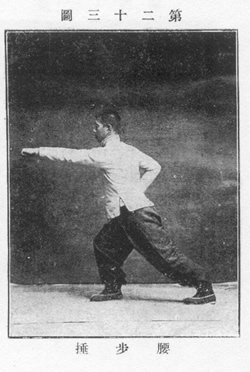

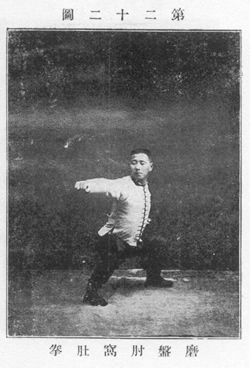

The figure most commonly associated with the Jingwu's early martial arts program is Huo Yuanjia. Huo Yuanjia was a practitioner of the Mizhongquan system, which is a variant of Northern Shaolin. The name Mizhongquan means literally "confused tracks boxing." The Jingwu's signature routine is called "cross shaped routine," which is presented in its entirety in their Anniversary book with photos, text and a footwork diagram. The routine was clearly held in high regard. According to the Anniversary book, "It was said, 'If you know cross shaped form, you can defeat half the heroes in the world.' This may sound like boasting but it shows how popular the routine was."

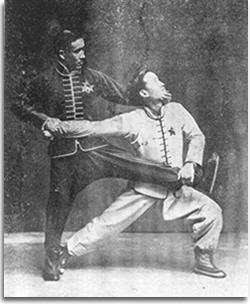

The "cross shaped routine" is shown in detail with photographs and written description. There is also a diagram that shows the layout of the form. The form basically consists of one line that goes up and back. This training routine was also recorded in a separate book that featured the same photos. The person performing the routine in the photos was Zhao Lianhuo. Zhao was born in Zhao Family Village in Hopei. He was an expert in Shaolin boxing and had been hired by Huo Yuanjia to be the head martial arts teacher for the Jingwu Association. Soon after Huo's death, Zhao Lianhuo was named one of the chairmen of the Jingwu Association.

This routine that "could defeat half the heroes of the world" was one of the 5 core routines of the Jingwu program. According to the Anniversary book, the Jingwu Association's martial arts program was composed of "5 Battles Boxing," which consisted of 1) paired boxing (two-person pre-arranged routines); 2) big boxing routine; 3) short boxing routine; 4) escaping routine; 5) cross shaped routine.

The Jingwu curriculum aimed at giving students an all-around sample of the best of Northern Shaolin. The goal was to keep it interesting by having a variety of different martial arts routines.

The Jingwu program had many fine martial arts teachers during its Republican Era, and the Jing Wu Associations now scattered about the world are equally blessed with many outstanding instructors. This is made all the more important because Huo Yuanjia passed on quite early in the Jingwu's history, and the high quality of martial arts instruction for which Jingwu is noted owes heavily to the multitude of teachers who taught for the Jingwu over the years.

Huo Yuanjia's Martial Arts

Huo Yuanjia's Martial Arts

One thing needs to be pointed out about Huo Yuanjia's martial arts, and this is not discussed in the Anniversary book but is mentioned in other records. Mizongquan is a very complex and physically demanding variant of Northern Shaolin, and it was the "indoor" system of Huo's family. By that we mean it was a system of martial arts that was kept secret and reserved exclusively for members of Huo's family. This may sound eccentric to modern ears, but keeping martial arts systems secret in China was commonly done for the same reason modern businesses keep "trade secrets" for competitive advantage. Martial arts was a business in China, and the systems were the "trade secrets" of the business.

When Huo Yuanjia started to teach the general public at Jingwu, he changed the name of what he was teaching from Mizongyquan ("Mizong boxing system") to Mizongyi ("Mizong techniques"). The implication was that Huo did not want to reveal his clan's closed door system in its entirety. So he picked various techniques and training routines out of his family's system and then changed the name of the system slightly.

The Huo/Jingwu Legends

The Huo/Jingwu Legends

The historical reality of the Jingwu Association is only part of the picture; in many ways the myth and the legend of the Jingwu is equally important. So examining the Jingwu legend can reveal more of the Jingwu's story. In this section we will compile typical elements and episodes from the life of Huo. But keep in mind that contemporaneous, trustworthy accounts of Huo's life are non-existent.

Though the very first photo in the Jingwu Anniversary book is a big, handsome full-page portrait of Huo, bearing the caption, "Founder of Jingwu," the book does not retell any of the stock stories of his life (e.g., how he fought the evil slimy British dude, recovered his friends dead body from the corrupt Germans, posted the notice in the paper about weak men of Asia, was poisoned by that sleazy Japanese doctor, or any of the other stuff in the Bruce Lee/Jet Li movies). In fact, the Anniversary book does make any further mention of him, except in passing.

All we really know about Huo is the kind of general information one might find on a basic job application - born such-and-such a place, such-and-such a year, parents are so-and-so, has children, studied Lost Track Buddha Disciple system and taught very briefly for the Jingwu Association. In a sense, this makes the legend as important as the few known facts.

All we really know about Huo is the kind of general information one might find on a basic job application - born such-and-such a place, such-and-such a year, parents are so-and-so, has children, studied Lost Track Buddha Disciple system and taught very briefly for the Jingwu Association. In a sense, this makes the legend as important as the few known facts.

As professional historians, we must repeat the fact that almost no reliable information exists concerning Huo's life. Nonetheless, we will retell the standard "Huo myth" because it does have value - not as historical fact but rather to provide insight into what the Chinese, and for that matter Westerners, want in a martial arts hero. The myth is valuable as a "cultural mirror," reflecting what the Jingwu wanted for its image.

The Foreigner Fights

In both Chinese and English retellings of the Jingwu legend, the centerpiece of the story is usually the "foreigner fights" that Huo Yuanjia engaged in. Martial arts historians are often asked about "the truth" of these fights. Before attempting to determine who Huo actually fought, we need to clarify a couple of things that will have a major influence on the answer. First, the only information we have about Huo comes from either the Jingwu Association (which uses his name as their founder, so there is an inherent conflict of interest there), or from his descendants (who often try to make money off their respected grandfather's name and fame, despite never having laid eyes on him). Neither source can be trusted to be entirely "objective." Secondly, we have no reliable contemporaneous information about Huo other than some very basic information. The third complication is that the legend of the foreigner fights was probably a creation of Chinese journalists. The turn of the century was a time of pulp journalism both in the West and the East. Inflammatory and exaggerated stories were the norm, and journalists knew that any story with a racial aspect would ad "fuel to the fire" and increase newsstand sales. The point we are driving at is that turn-of-the-century newspapers are a very dubious source of information.

Turning to the issue of "fights," part of the confusion about the Huo legend has to do with the meaning of "fight." Are we talking "worked matches," which were the mainstay of turn-of-the-century stage-fighting all over North America and Europe. A "worked match" was scripted and had a predetermined winner. Since worked matches often tied in with gamboling fraud, another word for a worked match is "a fix." Another common type of "fight" was an exhibition fight; it had rules, but neither side was trying to kill the other, the goal was just to "look good." The third possibility was a real competitive fight where the competitors were roughly equal in skill and both were "there to win." A real competitive fight was a great rarity at the turn of the century, at least in Europe or North America, and one suspects they were uncommon in China too. The bottom line is, from a historian's standpoint, it is quite hard to say which fights were worked matches, exhibitions or real fights.

Turning to the issue of "fights," part of the confusion about the Huo legend has to do with the meaning of "fight." Are we talking "worked matches," which were the mainstay of turn-of-the-century stage-fighting all over North America and Europe. A "worked match" was scripted and had a predetermined winner. Since worked matches often tied in with gamboling fraud, another word for a worked match is "a fix." Another common type of "fight" was an exhibition fight; it had rules, but neither side was trying to kill the other, the goal was just to "look good." The third possibility was a real competitive fight where the competitors were roughly equal in skill and both were "there to win." A real competitive fight was a great rarity at the turn of the century, at least in Europe or North America, and one suspects they were uncommon in China too. The bottom line is, from a historian's standpoint, it is quite hard to say which fights were worked matches, exhibitions or real fights.

Further clouding matters, none of the foreigners involved in these fights have names that are traceable by modern historians. The "Russian wrestler" in the park fight doesn't even have a name - not much to go on there. Then there was the British boxer named Hercules O'Brien. Hercules is a stage name, and O'Brien is a common British Isles family name, so modern historians have no idea who this was. Having said this, we are not saying Huo never fought a foreigner or even several; what we're saying is that it cannot be historically verified. And that makes it a legend.

About

Brian L. Kennedy :

![]() Brian L. Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo are the coauthors of the recently released JINGWU: THE SCHOOL THAT TRANSFORMED KUNG FU. Their earlier book was CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS MANUALS: A HISTORICAL SURVEY.

Brian L. Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo are the coauthors of the recently released JINGWU: THE SCHOOL THAT TRANSFORMED KUNG FU. Their earlier book was CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS MANUALS: A HISTORICAL SURVEY.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article