By Emilio Alpanseque

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

For foreigners fascinated by Chinese culture, especially in the areas of Daoism philosophy and the popularly called “internal” martial arts, what experience could be more gratifying than receiving instruction bounded by the magnificent slopes and valleys of the very same place where according to legend these practices originated? Certainly, the Wudang Mountains (武当山) have become a mandatory destination for those who want to explore these traditions, which were strongly revitalized during the late '80s and early '90s. For this article, we travelled to the area and met with Master Yuan Xiugang (袁修刚), one of the most prominent experts of his generation, who shared with us his recollections and views around traditional Wudang culture and its position in today’s society.

For foreigners fascinated by Chinese culture, especially in the areas of Daoism philosophy and the popularly called “internal” martial arts, what experience could be more gratifying than receiving instruction bounded by the magnificent slopes and valleys of the very same place where according to legend these practices originated? Certainly, the Wudang Mountains (武当山) have become a mandatory destination for those who want to explore these traditions, which were strongly revitalized during the late '80s and early '90s. For this article, we travelled to the area and met with Master Yuan Xiugang (袁修刚), one of the most prominent experts of his generation, who shared with us his recollections and views around traditional Wudang culture and its position in today’s society.

The Wudang Mountains

The Wudang Mountains are a place of spectacular natural beauty. Located in the northwest area of Hubei Province, they are like something out of a wuxia epic novel. Covering over 120 square miles, they consist of countless peaks, cliffs, caves, valleys, streams and more, together with a magnificent ancient building complex erected to fit the natural contours of the cliffs, and sometimes to mirror them. The first buildings of this area were constructed in the early Tang Dynasty (618–907), and as a whole represent the architectural achievements over a period of nearly 1,000 years, listed by UNESCO as a World Cultural Heritage Site since 1994. At present, numerous palaces, temples, monasteries, nunneries, and other structures remain in place and are currently preserved through periodic and well-planned maintenance and protection.

Wudang has a deep historical and cultural significance as one of the most important Daoist sacred lands. It is the central site of worship for the deity Zhenwu (Perfect Warrior 真武), receiving the appellation “Great Peak” (大岳) since the times of Emperor Yong Le (永乐帝 – reign 1402–1424). Becoming home to an active Daoist community that has endured for centuries, it gave birth to rituals and unique methods of health preservation, as well as fostering martial arts that may have been adapted and utilized by locals to protect against intruders. In the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), about 33 palaces and structures such as the Zixiao Gong (Purple Heaven Palace 紫霄宫) and the Yuxu Gong (Jade Void Palace 玉虚宫) were built. Wudang emerged as the biggest site for royal Daoist rituals in China.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Daoism had fallen out of favor; however, thanks to masters like Xu Benshan (徐本善), the abbot of Zixiao Gong, Wudang traditions continued to be practiced at least until the early 1930s. Xu was said to have exchanged his skills with many visitors including the military leader He Long (贺龙) and the Xingyiquan/Baguazhang masters Fu Jianqiu (傅剑秋) and Pei Xirong (裴锡荣), the latter becoming a formal Wudang disciple in 1929. Then the inevitable happened during the establishment of the People's Republic of China (1949–present) and especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when China's “four olds” – old ideas, old customs, old habits and old culture – came under attack. Wudang was targeted and most activities there were suppressed, with many members being persecuted, imprisoned, killed, or forced to flee to other areas and become recluses.

Wudang’s Renaissance Period

In 1979, China legalized religious practice. In 1984, the Wudang Daoist Association (武当道教协会) was founded and started to collect, preserve and disseminate records and materials on Wudang traditional culture under the leadership of Wang Guangde (王光德). During this time, with the assistance of members of the Wuhan Sports University, multiple inheritors of Wudang boxing were surveyed around many provinces of China, with a few of them – like Guo Gaoyi (郭高一), Zhu Chengde (朱成德), and others –returning to Wudang to contribute to the formulation of a complete body of knowledge, issuing in a new era in the transmission of this legacy. For this purpose, two lineages or sects were appointed under the association: the Sanfeng Pai (三丰派) led by Grandmaster Zhong Yunlong (钟云龙), and the Xuanwu Pai (玄武派) led by Grandmaster You Xuande (游玄德). A good number of other schools/masters can be found outside these two “official” sects as well.

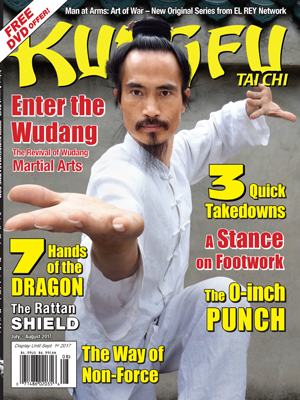

Today, Wudang’s nearby city of Shiyan boasts over 25 martial arts schools that follow the preservation efforts formulated by the association. Among them, the Wudang Mountain Daoist Traditional Kung Fu Academy (武当山道家传统武术馆), founded by Master Yuan Xiugang, is considered among the top choices. Born in 1971, Master Yuan, whose Daoist name is Shi Mao (师懋), started learning martial arts at the age of seven. He spent three years training in traditional Shaolin boxing in Henan province. In 1991, he arrived at Wudang with the help of his father after reading about their internal styles. Little did he know that he would eventually become a 15th generation disciple of the Sanfeng Pai under GM Zhong Yunlong. Master Yuan spent several years living inside Zixiao Gong following a strict full-time Daoist priest routine advocated to inheriting the essence of Wudang martial arts, health cultivation, internal alchemy, herbal medicine, acupuncture, and more.

“There Was No Boxing in Wudang”

In 1930, Chinese historian Tang Hao (唐豪) published the book, Study of Shaolin and Wudang (少林武当考), in which he mentions the lack of boxing theories or essays found in Wudang. However, Master Yuan begs to differ: “There has been a lot of misinformation about Wudang for many decades, very few resources, and very little knowledge. But times have changed and now we know much better. There were many boxing traditions in Wudang during that period. For instance, the style Taiyiwuxingquan (太乙五行拳) that surfaced at Wushu exhibitions in the '80s, where did it come from? This style was learned at the Zixiao Gong in Wudang with a lineage that traces back to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Then it was brought to Beijing in 1929, where it later spread to a few other regions prior to returning to Wudang by one of my grandmasters, Madame Zhao Jianying (赵剑英). In a similar manner, the Wudang Daoist Association completed a comprehensive study, learning the systems and recovering historical materials from all over China, collecting around 10 million words worth of information to our libraries.”

In 1996, Professor Kang Gewu (康戈武) wrote in his comprehensive Chinese Wushu Practical Encyclopedia (中国武术实用大全) that the styles of Xingyiquan (形意拳) and Baguazhang (八卦掌) bear no relation to Wudang. But Master Yuan reveals: “Historians work with limited information, usually based on reports from the persons who made the styles popular, including few documents or oral accounts made by their different students, etc. For example, Dong Haichuan (董海川) is famous for popularizing Baguazhang in Beijing, but do they know how did he obtain all the skills that made his art so unique? His Palm Changes? His Circular Walking? Actually, there are records of Daoist influences in his past, like Bi Dengxia (毕澄霞) or Bi Chenxia (毕尘侠), but we must also note that martial artists had to be very secretive during this period. Claiming association with the wrong person could have tragic results. So even if Dong Haichuan had declared to his students who were his masters, can we know if he was telling the whole truth?”

A Closer Look at the Principles

Master Yuan strongly believes that the principles behind these styles is what determines their relationship to Wudang: “Yes, the Daoist principles are not dogma, but a guide for us to understand Wudang. When Zhang Sanfeng (张三丰) came to Wudang to pursue immortality, he was able to combine ancient Wushu combat theory with ancient Daoist principles such as the Yin and Yang (阴阳), the Five Elements or wuxing (五行), the Eight Trigrams or bagua (八卦), and internal alchemy methods or neidan (内丹), establishing the concepts behind Wudang internal boxing with attention to self-defense as well as health preservation, on nourishing rather than wasting, using intention instead of force, letting softness overcome hardness, etc. This is his legacy, which was passed down to several disciples like Wang Zongyue (王宗岳) or Zhang Songxi (张松溪), and later became a major influence to other styles after generations of succession and development.”

Master Yuan further reflects: “There is no doubt that Taijiquan, Xingyiquan, Baguazhang and their derivatives became popular and spread in a traditional manner in many regions of China. But there are principles contained within them that were carried out by Daoists in previous generations, though this information may have never been disclosed. For example, most people know Yang Luchan (杨露禅) for teaching Taijiquan in Beijing and for learning in the Chen Village, but why does his style look so different to the one practiced by Chen Village representatives today? There must have been other sources, other teachers. Could it be that Jiang Fa (蒋发), who learned from Wang Zongyue, who in turn learned from Zhang Sanfeng, was the one who taught him and others in the Chen and Zhaobao villages the internal boxing principles? There must be an explanation as to why the Taijiquan observed in the Chen Village, although they have worked a lot in the last decades to make it softer, is still very much like paochui (炮捶), when in fact Taijiquan originated from internal alchemy as the core.”

Learning Stages and Daoist References

Master Yuan has preserved the traditional way of teaching. “In Wudang we do not follow the modern Wushu ways which primarily focus on performance for competition with a high potential for injury. Our traditional training focuses on “form” as well as “intention.” However, our training methods may also differ from what other traditional “folk” Wushu masters or schools do. For example, some Taijiquan schools may base their practices to Taijiquan forms, drills and push hands only. Do you think that after a period of time just doing slow forms you will be able to stand up against a practical fighter? Fighting also requires moving fast. How can you achieve that? Perhaps there are better methods, but most importantly: acquiring self-defense skills is not the ultimate aim of our practice. Wudang Wushu is in fact an integrative training method that consists of three Daoist concepts used as references: wuji (无极), taiji (太极), and liangyi (两仪).

“First, we condition our physical bodies by drilling the basic methods of hands, eye, body, stances (手眼身步法) to build up the correct levels of flexibility and strength required, so that later we can advance and also cultivate our essence, vital force and spirit (精气神). What are the three concepts? Wuji is a state of void with no yin and yang, taiji is the ultimate balance of yin and yang, and liangyi is the individual manifestation of yin and yang. The practice of routines like xuanwuquan (玄武拳) embody the liangyi concept, with slow movements followed by explosive ones, including sudden energy release or fali (发力) techniques and some features from Xingyiquan and Baguazhang. In contrast, the practice of Taijiquan routines allows to develop the taiji component as all movements are executed by harmonizing soft and hard, opening and closing, etc. Lastly, our emphasis in Daoist teachings reaffirm the importance of the wuji concept, which is achieved through meditation and internal alchemy methods. Returning to wuji is what enables the practice and cultivation of the Dao through martial arts (以武修道).”

Wudang Wushu: A Self-Transformation Art

Master Yuan’s explanations and definitions are in line with the traditional notions that martial arts and the Dao share the same origin and harmonize into one (拳道同源,拳道合一). Albeit with some caveats around its revival and safeguarding, Wudang Wushu stands today as a very strong offering across the full spectrum of martial arts and health preservation methods. Many types of students travel to the Wudang Mountains, from martial arts enthusiasts responding to the promotion of Wushu through movies and television; to students interested in acquiring self-defense skills to strengthen their bodies and repair health conditions; to local kids sent in by their parents to remain closer to traditional culture and stay away from videogames and junk food; to martial arts coaches, teachers, or school owners who look to upgrade or refine their knowledge; to persons interested in the pursuit of immortality. No matter how different their bodies, minds, social conditions, objectives and dreams may be, Wudang Wushu will certainly hold great benefits to all of them and will endure for many generations to come.

Understanding Wudang Sanfeng Taijiquan

The most popular style of Taijiquan found in the Wudang Mountains today is called Sanfeng Taijiquan (三丰太极拳). A few routines of this style first surfaced in the late '80s and early '90s. Subject to both admiration and a certain skepticism, it has spread rapidly across all continents over the last decade thanks to the promotion efforts by members of the Sanfeng Pai. In this section, we will attempt to trace its historical evolution and main characteristics.

The school of Sanfeng Taijiquan, as we know it today, is primarily compiled based on the inputs and knowledge of Grandmaster Guo Gaoyi and his disciple Zhong Yunlong. Guo Gaoyi was an inheritor of various Wushu traditions acquired from different masters during his life. Born in Henan in 1921, he was first exposed to several Shaolin-based styles. Later, during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) in the Northeast, he had the opportunity to learn other systems, possibly including Taijiquan, from Yang Kuishan (杨奎山) and Guo Yingshan (郭应山), two students of the legendary General Li Jinglin (李景林) from the Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute. (Note: Li Jinglin learned Yang style Taijiquan from Yang Luchan’s sons and Wudang sword from Song Weiyi (宋唯一), a member of the Wudang Dan Pai (丹派)). Next, Guo moved to Mount Lu (闾山) in Liaoning and learned Wudang Taijiquan and other internal training methods from Yang Xinshan (杨信山), a Daoist priest of the Wudang Sanfeng Ziran Pai (三丰自然派).

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Guo was forced to return to Henan, but he later moved to Mount Tongbai (桐柏) to become a member of the Wudang Longmen Pai (龙门派) in 1981 and followed Daoist priest Tang Chongliang (唐崇亮), with whom he continued to refine his Wudang practices. (Note: Tang Chongliang learned Wudang Taijiquan and other methods at the Zixiao Gong with Abbot Xu Benshan). In 1983, Guo relocated to the Wudang Mountains, joining the Wudang Daoist Association in 1984 as a head Wushu instructor until 1988. During this period, the Wudang Daoist Association was busy consolidating the Wudang Wushu curriculum, and the standard routines of Sanfeng Taijiquan emerged, which included the Sanfeng Taijiquan 13 Postures – known as the mother form of the style – followed by the 108-Step Wudang Taiji, and a shorter derivative 28-Step Wudang Taiji created in the '90s with similar sequences but less repetitions and a few removals for the sake of simplification and easier dissemination.

Having identified the sources and the process, the resulting routines of Sanfeng Taijiquan can be better conceptualized. Upon observation, the style has a soft and light external appearance which resembles the movements of the Yang style, like floating clouds or flowing water, except with greater internal firmness, like an iron bar wrapped in cotton, with a few angular and circular movements that stand out from other styles. Sanfeng Taijiquan emphazes the development of useful martial applications that implicitly include the “13 Postures” (十三势) that consolidate the foundation of Taijiquan: peng (ward off 掤), lu (roll back 捋), ji (press 挤), an (push 按), cai (pluck 採), lie (split 挒), zhou (elbow 肘), kao (bump 靠), qianjin (advance 前进), houtui (retreat 后退), zuogu (left step 左顾), youpan (right step 右盼), and zhongding (central equilibrium 中定). Moreover, the movements of Sanfeng Taijiquan fully observe all principles written in Zhang Sanfeng’s Canon of Taijiquan (太极拳经), the Treatise of Taijiquan (太极拳论) of Wang Zongyue, and the Ten Essentials of Taijiquan (太极拳十要) of Yang Chengfu, among other classical texts.

The Sanfeng Taijiquan 13 Postures routine is not a form consisting of 13 movements, nor should it be confused with other forms with similar names created by physical education institutes or universities to demonstrate the “13 Postures” by using movements from simplified Taijiquan. The Sanfeng Taijiquan 13 Postures form is considered a first generation internal boxing routine consisting of 13 sections, also called “postures” (势) or in some cases “positions” (式) for disambiguation, which add up to 60 movements in total. Depending on the desired training effect, this form can take up to 15 minutes to complete, and each one of the 13 postures is named according to its function. For example, baoqiushi (holding a ball posture 抱球势), dantuishi (single hand pushing posture 单推势), tanshi (extending forward posture 探势), tuoshi (holding up posture 托势), etc. Notice that in this case the 13 postures do not correspond to the “13 Postures” of Taijiquan either, although the latter are the guiding principles behind each action or movement of the former.

It is said that several generations of Wudang descendants continued working on expanding the 13 Postures. By the time of Xu Benshan, the Taijiquan practiced exclusively at the Zixiao Gong already had a 108-Step routine, created by joining elaborations, repetitions and variations of the original 13 postures into a cohesive and longer form. It’s worth noting that many local systems also claim to have evolved from the 13 Postures such as Jiugongquan (九宫拳), Xuangongquan (玄功拳), Chunyangquan (纯阳拳), as well as other schools of Taijiquan in Wudang and in other regions. Today, the 108-Step Wudang Taiji form is considered a second generation internal boxing routine which takes more than 30 minutes to perform, being the method of choice for health and energy cultivation. The 108 movements are arranged into 8 sections and include most of the actions present in other schools of Taiji such as lanquewei (grasp the sparrow’s tail 揽雀尾), shouhuipipa (hands play the lute 手挥琵琶), louxiaobu (brush knee in twisted step 搂膝拗步), danbian (single whip 单鞭), etc. And their individual practice will provide additional information on the martial applications and strategy of Taijiquan.

Paraphrasing Master Yuan Xiugang, martial arts practitioners should not be over-worried about one particular routine or another, and focus their attention on understanding the principles behind the movements, which can only be achieved by following a qualified master with conviction and without wavering. A new routine can be made up in one day, but under the heaven there is only one Taijiquan!

| Discuss this article online | |

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine July + August 2017 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2017 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Emilio Alpanseque :

For more information about Master Yuan Xiugang visit WudangGongFu.com. Emilio Alpanseque currently teaches in El Cerrito, CA, and can be contacted through his website EastBayWushu.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article