By Emilio Alpanseque and Matt Wong

Under the spotlights of a crowded sports arena, a contemporary Nanquan (南拳) player in his customized fluorescent silks sparkling with sequins walks onto the carpet, spreads his arms, rapidly pumps his hands out in tiger claw strikes while screaming fiercely at the sky, and prepares for a jumping inside kick with a 540-degree rotation followed by a single jump back flip. On the other side of the city, standing in the middle of a peaceful park, a traditional Hung Gar (洪家拳) student wearing old sweatpants and a worn t-shirt gathers his energy breathing and pressing his arms out in an isometric fashion, then slides his feet apart and begins the classic stationary stance-work of the centuries-old Taming the Tiger form.

Under the spotlights of a crowded sports arena, a contemporary Nanquan (南拳) player in his customized fluorescent silks sparkling with sequins walks onto the carpet, spreads his arms, rapidly pumps his hands out in tiger claw strikes while screaming fiercely at the sky, and prepares for a jumping inside kick with a 540-degree rotation followed by a single jump back flip. On the other side of the city, standing in the middle of a peaceful park, a traditional Hung Gar (洪家拳) student wearing old sweatpants and a worn t-shirt gathers his energy breathing and pressing his arms out in an isometric fashion, then slides his feet apart and begins the classic stationary stance-work of the centuries-old Taming the Tiger form.

These two Chinese martial artists, practicing their own respective styles, would seem to have nothing to do with one another, but in fact they share the same roots in Hung Gar. Despite the gymnastics additions and dramatic flourishes, the fundamental principles of modern Nanquan were set forth by great Hung Gar masters. Throughout the history of Nanquan, the relationship between the two branches of Chinese Wushu - both its differences and similarities - can be seen, especially through the invaluable insight and first- person accounts shared for the first time by the traditional Shaolin Temple Hung Gar inheritor and renowned Hong Kong actor, Grandmaster Chiu Chi Ling (趙志淩).

Rediscovering Wushu

To understand the history of modern Nanquan, we must revisit the origins of modern Wushu. In this regard, Grandmaster Chiu explains, "After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the new government got together to try to organize their traditional arts after decades of chaos. They held several national traditional sports demonstrations in the early '50s and some years later. They had a special committee to develop martial arts, but many martial arts masters of the South were not in the country anymore as many of them supported the recently defeated and exiled Nationalist government (KMT), so they left to open schools in Hong Kong, Taiwan or Southeast Asia at that time."

Political uncertainty, economic crisis and twelve years of war had ground Chinese martial arts development to a standstill. However, they started to flourish again within the following years. By 1953, at the National Ethnic Minorities Traditional Sports Games (民族形式体育运动) organized by the State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports (国家体育总局) in Tianjin, there were more than 300 hundred Wushu demonstrations.

Elaborating on the topic, GM Chiu recalls, "Yes, but they had very few masters that really knew southern martial arts then; it was more like 20 years of interruption. In 1957, my father Chiu Kau (赵教) was invited from Hong Kong to participate in the Guangdong Province Wushu Exhibition (广东省武术观摩会) in the city of Foshan. He performed our Tiger and Crane routine (Hu He Shuang Xing Quan - 虎鹤双形拳), which represents the true kung fu lineage of the 19th century Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-Hong (黄飞鸿), and got first place. He also received a certificate of merit signed by Chairman Mao Zedong (毛泽东)."

The following year the Chinese Wushu Association (中国武术协会) was established in Beijing and soon developed a repertoire of new Wushu routines assimilating the martial arts of northern China along standard guidelines and principles and thus creating modern Changquan (长拳) using five classic northern styles: Chaquan (查拳), Huaquan (花拳), Hongquan (洪拳), Paoquan (炮拳) and Huaquan (华拳). GM Chiu concurs, "Yes, it was all based on what we call bei pai (北派) or northern styles; at that time they did not have anything representing the martial art styles of southern China."

Creating Modern Nanquan

The southern styles were not represented in the first iterations of modern Wushu. The commission published the first modern Wushu competition rules in 1959 but there was no specific division for the southern styles. Moreover, at the first All-China National Sports Games held in - September of that same year, the Wushu events did not have a Nanquan division. However, after some consideration, Nanquan was technically established as a separate entity from Changquan. Here GM Chiu discusses some of the early challenges that the new Wushu association faced: "They had problems to include southern styles into the new Wushu. Do you know how many martial art styles we have in the south? And they are all different. How can you standardize all these different traditions into one single Nanquan? Also, what were the judges going to do? They really didn't know the difference, and they could not judge our stances and movements according to northern standards. If we stand up on the carpet and hit a typical inner abduction stance (er zi qian yang ma - 二字箝羊马) with our knees turned-in, they would probably have given us a deduction!" he jokes. "So, it was very difficult."

The Nanquan classification was unwieldy and no rules or guiding principles existed mainly because the committee members themselves were all northern stylists and even with the shared Shaolin background of many of the popular southern styles, the individual characteristics of each style still varied enormously. So it could be said that Nanquan existed on paper but not in practice. GM Chiu remembers, "In 1958, my father went to Beijing to compete and perform in front many important dignitaries, including Mr. Li Menghua (李梦华), then Minister of the State Physical Culture and Sports Commission of China and president of the Chinese Wushu Association. When my father performed our traditional Tiger and Crane, their technical experts approached him and asked him where he was from, then - learning he was from Hong Kong and his performance was very strong - they decided to model modern Nanquan mainly on Hung Gar style."

Indeed, the Chinese Wushu Association held the first National Wushu Games (全国武术运动会) in Beijing in 1958 and received 260 athletes from all over the country. Apart from the presence of GM Chiu Kau, the Guangdong province team had several other exponents including Chen Changmian (陈昌棉), who would later become instrumental in modern Nanquan development. GM Chiu adds, "Yes, they did have several other masters from Guangdong, but I think they practiced more Jingwu (精武) styles than Hung Gar. It was my father who could show the purest version of the Southern Shaolin Temple martial arts traditions."

Starting with the Tiger and Crane

According to Professor Zhu Dong (朱东) of the Shanghai Sports Institute, the modern Nanquan division was tested for the first time in a Junior Wushu competition in 1959 and declared an official competition division at the National Wushu Championships of 1960 in Zhengzhou. Since the driving goals of the new sport Wushu were simplification and conformity, in 1961 the technical committee opted to make the Tiger and Crane routine part of the standard Nanquan teaching curriculum. The pattern had worked well earlier with the 24-Step Simplified Taijiquan routine and others, so the same idea was applied and the results were quite successful.

The new routine was much more concise; the number of repetitions of main movements was decreased and some others were eliminated, resulting in 69 movements that can be performed within 3 minutes. In this regard, GM Chiu responds, "Hung Gar routines are much longer than that; the traditional Tiger and Crane has 118 movements. But because we are not practicing for a specific competition, it can be tailored to the needs of the practitioner, the space and the moment. In Hung Gar, sometimes we can practice a routine for 20 or 30 minutes."

Another important change was that the names of all movements were changed to the new nomenclature, replacing the poetic titles with more practical names, prompting GM Chiu to lament, "In modern Nanquan all the classical names of the forms, the quanpu (拳谱), which are martial poems full of meaning, have been changed to straightforward names that only specify the movement done. For example the opening sequence name of "Dragon and Tiger Appear Together" (long hu chu xian - 龙虎出现) was changed to "Push palm and punch fist in empty step" (xu bu tui zhang chong quan - 虚步推掌冲拳). This represents a big difference. There is a lot of value on the traditional poems; many students around the world come to me specifically to study these texts and look for the special meanings."

Completing the Nanquan Curriculum

After a period of disruption caused by the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Wushu development resumed around 1974 and the State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports created a research team to reevaluate the teaching and practice of Wushu in 1979. The commission made sure this time to establish a functional modern southern component, and the result was a vast survey of traditional southern routines and old methods. The technical committee selected five popular southern family styles as the base of modern Nanquan, namely: Choy Gar (蔡家拳), Hung Gar (洪家拳), Lee Gar (李家拳), Lau Gar (刘家拳) and Mok Gar (莫家拳), following a similar approach to that used before with modern Changquan. Starting in 1980, Chen Changmian, now the head coach of the Guangdong Wushu Team, published a series of collective works on Nanquan such as the book Chinese Wushu Nanquan (中国武术南拳) featuring a complete set of beginner, intermediate and advanced forms.

As part of his developments, Master Chen compiled a modern Nanquan routine called Unified Nanquan (综合南拳) which has four sections representing four different traditional styles: Hung Gar's Tiger form, Lee Gar's Crane form, Hakka's Dragon form and Choy Lee Fut's Snake and Leopard form. The form was published first in China in 1981, and then in Taiwan in 1982 and lastly in Hong Kong in 1984 under the English name Kung Fu in South China in both Chinese and English. This represented one of the first efforts to promote Nanquan internationally; however, this routine was not widely adopted in part because the main effort of internationalization of Wushu was being handled by the Chinese Wushu Association from Beijing with little communication with the southern provinces, and in part because other cohesive Nanquan programs were also being promoted, such as the one from professor Zhu Ruiqi (朱瑞琪), originally from Guangdong, but representing the Beijing Sports University.

Taking Nanquan Worldwide

In 1986 the Chinese National Research Institute of Wushu (中国武术研究院) was established as the central authority for the research and administration of Wushu activities, and compulsory routines were authorized to further standardize Wushu at the international arena. Thus an official Nanquan International compulsory routine was created in 1989. Based on the optional routine of a student of Master Chen Changmian, Chen Lihong (陈莉红), this routine is a great representation of the Guangdong province modern Nanquan which is particularly heavy in Hung Gar movements.

During that same time period, other provinces such as Fujian and Zhejiang also carried out individual efforts to include certain elements or methods based primarily on their own southern Shaolin traditions such as Five Ancestors Boxing (Wuzuquan - 五祖拳), Dog Boxing (Dishuquan - 地术拳) and Black Tiger Boxing (Heihuquan - 黑虎拳). These eventually contributed distinctive techniques to the unified methods of modern Nanquan, though Hung Gar remained the predominant base.

In 1990 the International Wushu Federation (IWUF) was created, and all high-level international Nanquan competitions, including the World Wushu Championships and the Asian Games, began using this routine. But in 2004, when the IWUF adopted a new scoring system, informally known as the nandu (难度) or "Difficulty Degree" rules, the compulsory routines were replaced by optional routines created by the athletes and coaches with mandatory jumping difficulties borrowed from basic tumbling and from modern Changquan, along with a specific number of required basic Nanquan movements to help retain some of the original characteristics and techniques of the style.

Hung Gar, the Building Block

The ideals of Nanquan are heavily based on Hung Gar principles. Nanquan is characterized by low stance work, powerful stepping and large arm movements with the legs driving the waist and the waist pushing the arms into action. Though different techniques from other southern styles have been incorporated, these main points remain the underlying force behind modern Nanquan. While traditional in concept, execution of these principles was modernized beyond orthodox Hung Gar theory to make the stancework more linear and give a more exact body positioning to allow the movements to be clear for uniform judging and more visually appealing for performance.

Traditional movements like the classic swinging arm strikes like the "Eight Drunken Immortals" (zui jiu ba xian - 醉酒八仙), the double tiger claws attacks like the "Hungry Tiger Catches Ram" (e hu qin yang - 饿虎擒羊) or classic crane pecking techniques such as the "Crane's Beak Sinks Elbow" (he zui chen zhou - 鹤嘴沉肘) are all present in modern Nanquan - though they are simply known by their modern names. These core movements of Nanquan are executed in the same manner as in Hung Gar. Some stances are done lower and some arm movements show greater extension - generally performed with the body very upright for aesthetic reasons - all to make judging easier.

The power distribution of modern Nanquan is designed to emulate the power of Hung Gar, just in a more dramatic fashion. In Hung Gar dynamic tension is frequently used to help generate power and to strengthen the practitioner. This type of training can be seen in movements such as "Single Bridge Sitting on Horse" (zuo ma dan qiao - 坐马单桥) where the practitioner in horse stance uses isometric energy to slowly press out one hand with the index finger extended. Nanquan borrowed these techniques and many more.

Internal vs. External Criterion

The practice of Nanquan and Hung Gar have clear differences because the goals are almost opposite. GM Chiu reflects, "What is the objective of practicing Hung Gar now? Well, not only it is a complete system of self defense and health improvement, but it also represents an important connection to traditional Chinese culture, a direct link to the martial arts of the Shaolin Temple. So learning history and tradition is also an objective." While Hung Gar is primarily for internal personal development and cultural enrichment, Nanquan is a competitive sport with a distinct focus on demonstration. One style works from the inside out and the other is judged from the outside in.

From a more technical perspective, the Hung Gar practitioner focuses on driving all power through all the proper body meridians. The degree to which the arm goes out or stays in is not as important. For example, when extending the in isometric tension positions, the Hung Gar student focuses power in the index finger, with natural and free energy flowing though the body, while the other fingers are allowed to assume a natural relaxed position.

For the Nanquan player, the same movement focuses on precise arm and hand placement that ensures full extension of each movement. Little regard is given to focusing power in the extended index finger; rather, there is emphasis in locking the other fingers tightly into position for aesthetic value. Complete or even exaggerated extension of the movement is necessary to make sure the judges see the techniques easily and clearly. Despite these differences, the ideals of the movements are still shared, just expressed in very different ways.

GM Chiu comments, "Yes, Nanquan competitors move fast and look powerful, which represents the principle of hardness (gang - 刚) very well, but Hung Gar is not all about hardness. This is a common misconception. There is also a lot of softness (rou - 柔). Hardness comes out when we perform a routine, but when we practice, we always use hardness and softness together. There are a lot of subtle movements within the different body parts, subtle angles and forces that are applied. There is the internal "inch" power (jing - 劲), the Yin and Yang (阴阳), the Five Elements (wu xing - 五行), the Five Shapes (wu xing - 五形), the Twelve Bridges (shi er qiao shou - 十二桥手) and so forth. Hung Gar is very sophisticated. But again, since the objective is different, the final product is different too."

Retaining China�s Martial Traditions

Today, a Hung Gar student might watch a Nanquan routine and not see any of his style in there, just as a Nanquan player would likely not see anything of his form in an Iron Wire form. But to the great dismay or even disdain of both, the two styles are connected at their core by Grandmaster Chiu Kau and his Tiger Crane fist.

Being rooted with a strong foundation is a key requirement in both Hung Gar and Nanquan. This idea is expressed in the traditional Hung Gar maxim, "Sink and root yourself to be as stable and steady as Mount Tai" (luo di sheng gen, wen ru tai shan - 落地生根, 稳如泰山). The same can said for knowing the roots and history of the styles we study. GM Chiu realizes the importance of this and says, "If this information is not passed from generation to generation, it may be lost forever. That is why I am so happy that we can write about all these important matters and share with your readers."

| Discuss this article online | |

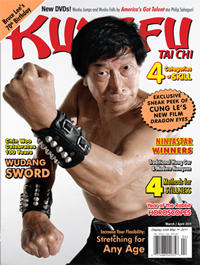

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine: March + April 2011 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2011 .

About

Emilio Alpanseque and Matt Wong :

![]()

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article