By Gene Ching with Gigi Oh

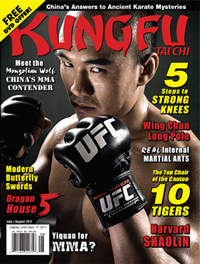

Only 48 seconds. That's all it took for Zhang Tiequan (张铁泉) to defeat Jason Reinhardt with a guillotine choke. For most viewers, it was a quick yet unremarkable bout on the UFC undercard, but for worldwide watchdogs, it was history making. Zhang fought Reinhardt on February 27, 2011 at UFC 127: Penn vs. Fitch in Sydney, Australia. The Ultimate Fighting Championship is the largest MMA promoter in the world. And like every global business, UFC wants to pillage the Dragon's Lair. The UFC wants the Chinese market. Zhang is the UFC's very first Chinese-born fighter.

Only 48 seconds. That's all it took for Zhang Tiequan (张铁泉) to defeat Jason Reinhardt with a guillotine choke. For most viewers, it was a quick yet unremarkable bout on the UFC undercard, but for worldwide watchdogs, it was history making. Zhang fought Reinhardt on February 27, 2011 at UFC 127: Penn vs. Fitch in Sydney, Australia. The Ultimate Fighting Championship is the largest MMA promoter in the world. And like every global business, UFC wants to pillage the Dragon's Lair. The UFC wants the Chinese market. Zhang is the UFC's very first Chinese-born fighter.

China has a tentative, yet developing relationship with MMA. With the richest traditional martial arts culture of any nation, China has already televised several popular martial-arts-based television programs including reality show contests like Kung Fu Star and Jackie Chan's Disciple, sparring championships like Sanda Wang (King of Sanda) and countless martial arts soap operas. China is a prime market for the fight sport. During the Beijing Olympics, China showed the world that it can develop international-level competitors in almost every sport very quickly. Zhang's fight career provides a telling gauge of the progress of MMA in the People's Republic of China. For starters, his record varies depending upon which website you might choose to surf. The UFC posts his record as 18-1-0, but Wikipedia says 13-1-0. Other MMA websites either cut-and-paste those stats for their own profiles of Zhang, or report slightly different results. The problem is that the Asian fight games are sometimes unrecognized, sketchy or simply remain untranslated.

Zhang began fighting MMA in Art of War, the Beijing-based event promoted by Andy Pi since 2005. He also fought in Legend, a Hong-Kong-based MMA production, and Universal Reality Combat Championship, another MMA league based in the Philippines. His first American MMA fights were for World Extreme Cagefighting, a Californian-league founded in 2001 and then bought out by UFC's parent company, Zuffa LLC, in 2006.

Prior to MMA, Zhang, being Chinese, fought in Sanda. And before that, Zhang practiced Bokh. Bokh is better known as Mongolian Wrestling. That's where Zhang's roots lie. He is a Mongolian native.

The Mongolian Wolf

Even Zhang's nickname varies. Most MMA sites dub him the Mongolian Wolf, but UFC shortens it to just "the Wolf." In Mandarin (if you've read another interview with Zhang, you should know that he doesn't speak English yet-another fact that many MMA websites overlook), the nickname he uses is chouyanlang (草原狼) or "Grassland Wolf." He adopted this during his years fighting in Sanda. "In my hometown, there were many wolves," explains Zhang in Mandarin. "They always came to steal livestock. My parents said they were sharp and smart. They take advice from their pack. They are organized, but still have wild animal blood. If a wolf bites you, you can beat him with sticks and it won't let go. You must pry their jaws open. They are persistent and tolerant. They insist to death."

Zhang's hometown is the Horqin Grasslands of Mongolia. He comes from tough farming stock. His family raised sheep, cattle and oxen, and grew feed corn. Their farm produced dairy products, wool, and meat, and in fact still does, as his parents, his brother and sister are all still there. He was the only one to leave the grasslands. The winters there are extremely cold and the summers are hot. Zhang remembers the vast fields of grass as very beautiful. "Because of drought, it's not as beautiful as it was before," says Zhang now.

It was in these pastoral lands that Zhang first started wrestling. "I started as a little kid," recalls Zhang. "There was nothing to play with when I grew up so all we did was wrestle. We had no toys, nothing. There was a regular elementary and middle school provided by the government. And when I became a teenager, I started helping around the farm, mostly as a shepherd, but other than that, it was just wrestling.

"Our games were born by nature. We just played. It's just in our blood. No one taught us. I've heard of an experiment where they got a hundred kids who didn't study any martial arts together to wrestle, and the kids instinctively developed universal techniques that were very useful. Those techniques are very practical. We still use the same techniques. I won all the time and became the leader of our group. I was born with a lot of natural strength and power. I really liked to wrestle, so I always tried hard to win."

Zhang draws inspiration from two personal heroes: Genghis Khan and Bruce Lee. As a Mongolian, Genghis Khan is a given. Zhang elaborates, "Genghis Khan is Mongolia's hero and ancestor. He occupied a huge territory. He has ambition, wisdom and courage. First, you have ambition, then the courage to follow through on it. And you can't win many battles without wisdom. Strategy is his wisdom." As for Bruce Lee, like most martial artists of his generation, Zhang grew up watching his movies. Movie watching was different in the grasslands. "There were no theaters and no television. Once a month, a huge white cloth was hung up between trees and movies were projected onto it. It was free, from the government. They showed three to five films back to back. All the kids just watched on open land. There were a lot of Bruce Lee movies. I'd watch past midnight. That was the only fun entertainment like that for kids where I was raised."

Bokh, Sanda and BJJ

Bokh is an integral part of Mongolia's cultural heritage. It stands alongside archery and horsemanship as the three martial skills cherished by Mongolians. Genghis Khan advocated Bokh for military training. Every summer, Mongolians celebrate Naadam, a national Bokh competition that draws hundreds of competitors. "Mongolians really respect the champions of Bokh," says Zhang. "We love to throw people down. We're very proud of this."

Most Chinese martial artists unfairly exclude Bokh from the roster of traditional Chinese martial arts. The Mongol Empire, which ruled China during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE), was established by Genghis Khan's grandson Kublai. Though often categorized as a "foreign" dynasty, the Mongol Empire made significant contributions to Chinese culture, enough so that Bokh deserves to be included amongst the diverse lineages of Chinese martial arts. And yet, perhaps due to its Mongolian secularity, it is seldom practiced outside of Mongolia.

Zhang admits that Bokh is limited to mostly leg techniques and throws. What's more, Bokh competitors wear a traditional leather top, which is good for grabbing, but not available in other forms of wrestling sports including MMA. When Zhang was 18, he studied some Greco-Roman Wrestling at a Physical Education College. It was his first formal training. As it turned out, he had to return home after a year to help out on the family farm. Greco-Roman Wrestlers do not wear tops that can be grabbed, so Zhang adapted his throwing methods early on. He believes his Bokh roots bring something new and unique to the Octagon. "No other style can compete with Bokh throwing techniques. We can throw them down easily."

College gave Zhang a taste of sports competition, and when things were settled at home, he journeyed to Hohhot to study the biggest fight sport in China, Sanda. "I like Sanda. There's so many ways to gain a point." Zhang's Bokh throwing skills transferred well to the sport, and he soon found himself in Xian, training under Coach Zhou Xuejun (赵学军). "I trained for almost six years under Coach Zhou. He was very strict. Every technique is so precise." However, Zhang didn't achieve the level of success he hoped he would. "I was only 3rd place in Youth Sanda. I was not that good."

Then an invitation from Beijing came. "When I was in Xian University training in Sanda, there was a club in Beijing that needed someone to fight MMA. So my Sanda coach, two other classmates and I went to Beijing. That's when I started fighting MMA. In 2005, I switched because a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu coach was there."

Zhang is quick to point out that Bokh and Sanda are both stand-up fighting styles and lack a ground game. "In Bokh, throw them down and it's done. In BJJ, there are throw-downs but it continues." Zhang enjoys the new dimension that BJJ brings to sport fighting. His victory over Reinhardt was his third win by guillotine, and some MMA pundits have ventured to say that it's Zhang's signature technique. Of course, the guillotine is distinctly Brazilian. "It's actually against the rules in Bokh. Bokh has regulations and is very polite. They stop the action if there are any issues." Earlier this year, Zhang was awarded his brown belt in BJJ. He believes this now makes him the highest ranking BJJ practitioner who was born in China.

MMA in China

To penetrate the Chinese market, one must first understand China. Solve the riddle of China and there's a fortune to be had. Staging Zhang's first UFC fight in Sydney was a good move, as Australia is relatively close to China, close enough to leak through the Great Wall. UFC also broadcast the fight live on Facebook in hopes of getting around China's government-controlled television networks. Unfortunately, Facebook is blocked in China. That's another Great Wall, the Great Firewall.

While Andy Pi's Art of War persists, and other small MMA promotions are emerging, it's all still about Sanda in China. Zhang explains the situation. "We do have some MMA here but not that much. It's mostly in Beijing, Xian and Hong Kong. Maybe there's some in Chongqing too, but mostly, Sanda is more popular. MMA lack an audience in China. Sanda is still very popular because it is promoted by the government. It's one of the Chinese martial arts, so there are more people watching. The government subsidizes Sanda games… Most people like to fight in Sanda. We still have the National Sports Games which is very prestigious. They don't want to give up the glory of that. The prize money is good too."

Prize money is a major factor. Fighters must earn their living by different means under Communism. Professional Sanda fighters are contracted on the municipal and provincial level. They become full time athletes, compensated with room, board, training and a stipend. MMA fighters have no government support. "There's not much prize money in China. In our fight club, China's Top Team, we have to give the fighters an allowance. They don't teach. They only train. They represent our club to go fight at open tournaments. Award money, if there is any, usually goes to the fighter up to 5000 RMB (around $750). Over that, the club will take 10%, but most of the time, they won't get that much award money.

"Most of those tournaments are local promoters, so they can't afford to invite foreign fighters. Going rate is $500 to $2000 USD for appearance fee for foreigners. The arenas are huge - they can have a large audience - however usually there are more giveaways than sold tickets. Usually, it operates under a sponsorship. Arenas are 3000-5000 seats typically. Those are the private promotions but they still need approval from the Martial Sports Bureau (wushu yindong guanxing ?Chinese?) and have to pay fees to them. We still need a lot more promotion here to let the Chinese people know what is MMA and the UFC."

Your Kung Fu Doesn't Work in the Cage

Since the rise of MMA in the early '90s, there has been growing animosity against traditional martial arts like kung fu. Kung fu has secured a firm hold in Hollywood, as well as the countless ballistic action films coming from China, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam. This made kung fu, or more specifically wushu, the most prominent pop image of martial arts. Fight choreography in film is, by nature, absurdly dramatic and highly stylized. In stark contrast, MMA challenges the effectiveness of kung fu with real combat, at least as real as you can get without causing much serious injury. Where were the flying kicks of wushu? Nowhere to be found in the cage. And how about all those animal styles from the kung fu movies? No tiger style, no drunken boxing, not even a kung fu panda.

There has been two UFC competitors who were trained in Chinese martial arts, Patrick Barry and Dan Hardy, both of whom studied Shaolin kung fu before making the switch to MMA. America's leading Sanda Champion, Cung Le, captured the Middleweight Championship belt in Strikeforce (another California-based MMA promotion that has recently been acquired by UFC's parent company, Zuffa LLC), striking an arm-breaking blow for the contribution of Sanda to MMA.

While Zhang has never studied the classical styles of Chinese martial arts like Shaolin or Taijiquan, he is quick to defend them. "Maybe they misunderstand. Most people only look at internal martial arts. We still have a lot of combat styles and can use those applications. This comment, 'Your kung fu doesn't work in the cage," shouldn't even exist. I think Sanda has a lot of solid techniques and basic applications. The only thing it lacks is the ground fighting. If combined with BJJ, then this comment won't exist. Conversely, if a BJJ fighter can combine Sanda into his game, it will make him a better fighter in UFC."

And yet, Zhang is well aware that he is a Chinese pioneer in MMA. "Right now, there aren't too many MMA fighters in China that can go international. There are maybe 20 or 30 at the most now. It's mostly lightweights, but there are a few 90-100 kg fighters. There isn't enough MMA available in China for fighters to test themselves. Some go to Russia to fight. In my fight club, we have about 10 pros, but only 7 could fight MMA."

Zhang is very optimistic about what UFC might bring to China. "If it gets more popular, then people might get more interested in fighting. I don't think people would give up traditional Chinese martial arts. Just because you like something, doesn't mean you'll give up everything to train it. You can watch it and enjoy it and keep up your style. On the contrary, I think it will inspire more people to learn Chinese martial arts and Sanda. Especially for me, I fully believe that kicks, punches and throws of Sanda are very useful for MMA. Those BJJ people don't really have those techniques, so that's why if they learn our Sanda, their technique will be even more complete, and vice versa.

"I think we have a lot of athletes in China that have the potential for UFC. Just because I could get in, I hope to make the opening. Also because I have 6 years of Sanda, I hope to inspire them."

Dreams of the Wolf

As the first Chinese-born fighter in the UFC, Zhang has been labeled by some MMA pundits as one of the most important fighters in the world now. The honor of the Chinese nation, of kung fu, and of his Mongolian heritage rest upon the success of his next fights. But Zhang shrugs it off. "I don't feel any pressure," he says laughingly. "My dream changes along with my age. When I was younger, I just wanted to be a professional athlete. After I achieved that, then I wanted to win. Then after winning, I wanted to be a champion. So my dream has been constantly growing. The only thing that has not changed is my love of the sport. That dream guides how I live my life. To be a farmer's kid and get selected to go to train as a pro, that is already a huge achievement. Now I'm fighting UFC!"

Zhang has no desire to immigrate to the United States. His fight club, China's Top Team, just expanded to a new larger facility, and as he was giving the interview for this story, everything was in transition. "I don't really speak English and I'm not accustomed to the living style," confesses Zhang. "And I want to get married."

He looks forward to the next time he steps into the Octagon, but he doesn't have his sights upon any particular fighter. "I think the most beautiful fighter is Mirko 'Cro Crop' [Filipovic\, but he's not in my weight class. I heard he lost a few fights recently, but I still like the way he fights. I hope to have another fight before the end of the year. If I can win another 3 or 4 fights, I can be a contender."

| Discuss this article online | |

| July/August 2011 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2011 .

About

Gene Ching with Gigi Oh :

Zhang Tiequan's Fight Club is China's Top Team

quan tian xia (拳天下) address: Si Hui, Jin di ming

jing Commercial St. Chaoyang District, Beijing, China

(200 meter from Si Hui Metro Station). 北京市朝

阳区四惠金地名京商业街 四惠地铁站200米

Email address: mmazhangtiequan@sina.com

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article