Usually, it doesn’t matter why you do the right thing, as long as you do the right thing.

In 2012 a group of scientists at West Virginia University received a small grant to run independent emissions tests on diesel cars, and they soon discovered Volkswagen had been installing deceptive software systems designed to cheat on standard tests by reducing emissions only when the software determined the car was being tested. As a result of this study, in September 2015 the EPA issued Volkswagen a notice of violation of the Clean Air Act, and within a few months, the CEO of Volkswagen stepped down, a number of executives and engineers were suspended, and plans to fix emissions on millions of cars via recall were put in place. Is it possible these actions represented a genuine effort to ensure such deceptive practices never happen again? Yes, it is possible. It is also possible that Volkswagen viewed the whole fiasco as a PR problem and let those people go for the sake of minimizing bad press and minimizing its own liability in court. Pragmatically speaking, it doesn’t matter what Volkswagen’s motives were, because genuine or otherwise, the steps it took to correct the problem would have been the same.

In 2012 a group of scientists at West Virginia University received a small grant to run independent emissions tests on diesel cars, and they soon discovered Volkswagen had been installing deceptive software systems designed to cheat on standard tests by reducing emissions only when the software determined the car was being tested. As a result of this study, in September 2015 the EPA issued Volkswagen a notice of violation of the Clean Air Act, and within a few months, the CEO of Volkswagen stepped down, a number of executives and engineers were suspended, and plans to fix emissions on millions of cars via recall were put in place. Is it possible these actions represented a genuine effort to ensure such deceptive practices never happen again? Yes, it is possible. It is also possible that Volkswagen viewed the whole fiasco as a PR problem and let those people go for the sake of minimizing bad press and minimizing its own liability in court. Pragmatically speaking, it doesn’t matter what Volkswagen’s motives were, because genuine or otherwise, the steps it took to correct the problem would have been the same.

The NFL found itself in a similar situation in 2005, when Dr. Bennet Omalu, played by Will Smith in the movie Concussion, published the results from the autopsy he performed on former Pittsburg Steelers center Mike Webster. Webster’s brain showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease typically associated with professional boxers. At first the NFL treated the discovery as a PR problem, and with the help of its Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) Committee, it spent years denying the mounting evidence for a causal link between football and CTE. Eventually, though, the evidence became too overwhelming to ignore, so in 2009 a spokesperson for the NFL admitted that concussions may have long-term effects, and in 2010, the MTBI Committee was disbanded. In the following years, the NFL made rule changes to reduce the number of big hits, and the league even made charitable donations for research into the detection and prevention of brain injury.

Now that the NFL has admitted it has a problem with CTE, can’t we just step back and let the commissioner fix it? Even if the league’s motives are limited to managing its image and its liabilities, shouldn’t we be able to trust that the actions it takes will start saving the brains and lives of our athletes? Unfortunately, it is not that easy. Unlike Volkswagen’s emissions problem, the NFL’s CTE problem lies at the center of scientific and medical processes we still don’t understand very well, and as a result, the public perception of the issue and the science behind the issue don’t always agree.

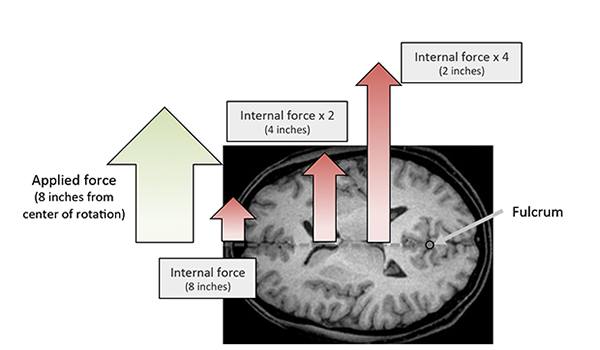

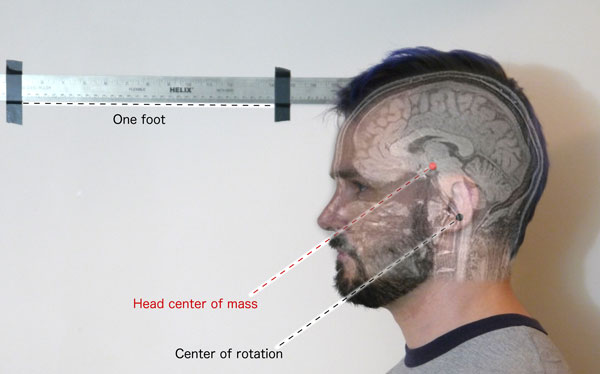

“A Top View of the Brain with an applied force to the chin. The head rotates around the neck at the base of the skull. The force felt at points close to the center of rotation will be much higher than the force felt farther away. This is, of course, a very simplified view,” from Fight Like a Physicist by Jason Thalken, PhD. Photo credit: Jason Thalken.

The differences between science and public perception are important here, because if the NFL genuinely wants to save the brains and lives of its athletes, it should follow the science; but if its primary concern is to look like it cares about the brains and lives of its athletes, it should follow the public perception of the issues instead.

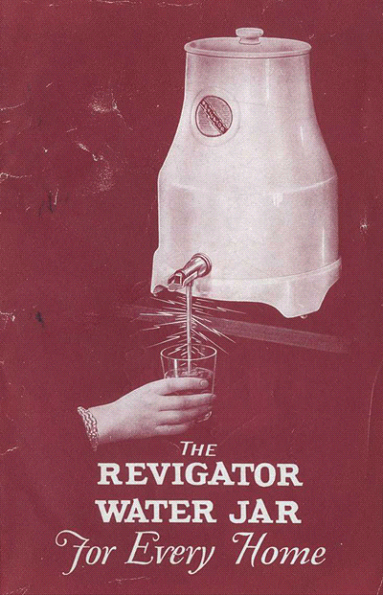

The Revigator Water Jar was popular in the 1930s. It was lined with radium because many people believed radioactive water had special healing powers. As you might expect, the truth turned out to be quite the opposite. Photo credit: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

People used to believe exposure to radiation would heal your body.

When it comes to emerging sciences, public misconceptions can be very persistent, even in the face of serious health risks. In the early 1900s, when the science of radiation was still very young, scientists detected radioactivity in the waters of some hot springs. Given the prevalence of legends about hot springs curing ailments and restoring youth, it did not take long for people to assume that radiation was the source of this magic. Despite evidence of the dangers of radiation poisoning emerging as early as 1915, consumer products touting the (imagined) health benefits of radiation, such as Revigator radioactive water jars and Doramad radioactive toothpaste, remained popular right up until the end of the Second World War.

In order to separate ourselves from the potentially sensitive issues at hand, let’s imagine for a moment that, back in the 1930s, football was played entirely in giant swimming pools filled with radioactive water—in order to rejuvenate the players and protect them from injury, of course. It would not take long for players to start falling ill and dying from a horrible disease marked by nausea, vomiting, anemia, fatigue, and high rates of cancer. Today we know how to identify radiation sickness, but back then, the diagnosis would have been less obvious, and many of the symptoms would have been attributed to the violence of the sport. Faced with negative press and a wide gap between science and public perception, our fictional aquatic NFL would have had two options: Fix the bad press by playing to public perception, or fix the problem causing the disease by turning to science.

For the aquatic NFL, the easier of the two options would be to fix the bad press. It could donate some money to help find a cure and it could implement some rule changes intended to make the game “safer.” It could even tell a story about how the game of football had become so violent, and the hits had gotten so big, radium water was no longer sufficient to keep the players safe, so it would need to invest in developing a stronger alternative, like uranium water.

If the aquatic NFL turned to science instead, its first step would have been to study people dying of similar conditions in other professions to better isolate the mechanism at the root of the problem. In doing so, it would have discovered the “Radium Girls,” women hired by the US Radium Company to apply radioactive paint to watch dials, many of whom fell ill and died. There was also the case of Eben Beyers, a golfer and a wealthy socialite who drank three bottles of radium water daily before losing part of his jaw and ultimately dying from a combination of radiation-induced cancers in 1932. These outside cases would have helped the aquatic NFL understand that the problem was the radioactive “safety water.” From there, the league would have had to make some major changes to the game, and it would have had to take on the unpopular and difficult task of reeducating all the fans as it started making some counterintuitive but incredibly important decisions.

It doesn’t take much digging to find out we’ve got it all wrong.

If the real-life NFL wants to fix its ongoing CTE problem, the first thing it needs to do is look at professional boxing and mixed martial arts. Fighters get CTE just like football players do, but the physics of the two sports are completely different. Putting the two sports side by side, along with a little science, helps correct a number of fundamental misconceptions we hold today:

“The human skull. This is actually an MRI of my head superimposed on a profile view of my head, so the location of the brain relative to the head is accurate. There is a 20 percent scale difference between the reference ruler and my head as a result of the depth of field” from Fight Like A Physicist by Jason Thalken, PhD. Photo credit: Jason Thalken

It’s about cumulative subconcussive damage, not countable concussions.

Boxers don’t tackle each other. They throw punches, very few of which transfer enough momentum to knock someone over. If punches are sufficient to cause CTE, why do we continue to focus on the big hits when it comes to the NFL? Furthermore, scientists have performed statistical analysis on the careers of fighters and football players, and that analysis determined that the number of concussions or knockouts is not as good a predictor for CTE as length of career. Taken all together, this means we need to stop talking about concussions as if they are the problem. CTE is the problem, and thousands of subconcussive blows during practice and training and games over the years accumulate more damage than concussions from big hits.

Rotational motion of the head is the key, not peak force reduction.

Fighters don’t aim for the forehead. A knockout blow is a punch to the chin that can get the head rotating, not a linear transfer of momentum to the brain. The distribution of the damage throughout the brain indicates that CTE is a result of sheer forces applied to axons in the brain as the head rotates, so why do we still rate helmets based on their ability to reduce the peak force during a linear drop test? This measurement is irrelevant to protecting the brain. We need to demand realistic testing and evaluation, using crash test dummies and computer-simulated brains that can estimate the sheer forces.

Football helmets and boxing gloves enable brain injury instead of protecting us from it.

Despite a number of cosmetic differences, the physics behind boxing gloves and football helmets are remarkably similar. Both contain compressible materials that absorb energy on impact, and both spread out the remaining energy over a large surface area. The result is boxing gloves and football helmets protect us from structural damage, such as cuts, bruises, swelling, skull fractures, and sensations of pain, but they do nothing to reduce the rotation of the head on impact. The problem is by protecting us from pain and structural injuries, we have removed many inhibiting factors that might lead us to stop taking blows. Instead of keeping us safe, gloves and helmets turn us into efficient brain-injuring machines.

Muay Thai/boxing headgear, baseball helmet, football helmet, and the human skull from Fight Like a Physicist by Jason Thalken, PhD. Photo credit: Jason Thalken.

Beware products pandering to public perception.

The NFL is not the only company operating by the public perception instead of science. The following products have all been proposed or marketed based on the fundamental misconceptions above. In some cases, they also make claims we could not possibly verify, given that the only way to diagnose CTE today is via autopsy.

Impact sensors: These sensors are worn by players and count the number of hits above a certain threshold. Unfortunately, many of these do not track rotational motion, and we have no estimates for what a reasonable threshold might be, so the counting is arbitrary.

Special mouth guards: Studies done to support these products were either anecdotal or made the mistake of measuring the peak force on the head for linear blows directly to the chin without rotation. There is no reason to believe they are effective.

Special tackling techniques: While it is probably true that some techniques may be better than others for minimizing brain injury, we currently have no method to determine which is which, other than speculation.

Headbands: Like many other products on this list, there is no reason to believe these reduce sheer forces on the axons in the brain as the head rotates.

Helmet covers: There are two different types of outer coverings made for football helmets, and neither one helps. One provides an extra layer of foam, which does not change the transfer of momentum to the head. Another type of helmet cover provides a slipping layer to allow for rotation. While it is good to see a product addressing rotation, it uses the wrong center of rotation. This product would only work if the human head rotated around its own center of mass, like the tip of a ballpoint pen.

Neckbands: These are ineffective and they are based on the misconception that the brain bounces around inside the skull. They are supposed to restrict blood flow to and from the brain. It is too early to know what additional negative side effects these might have.

Face cages: Football helmets already have extensive face cages, but some other sports, including baseball and combat sports, have started using face cages to keep the impacts farther away from the head. This might sound good at first, but the extra distance provides more leverage for rotating the head and makes the sheer forces on the brain much worse.

Pills or supplements: There is no way for us to measure the effectiveness of any products like these, so any product that makes bold claims should not be trusted.

“Better” helmets: Football helmets currently protect us against skull fractures but do nothing to stop sheer forces on the brain as the head rotates. Helmet companies have all released new helmets designed to do the exact same job helmets have always done, but more efficiently, swapping out one material for another. This is like swapping out your radium water for uranium water, and ultimately getting nothing but higher prices.

“Better” helmets: Football helmets currently protect us against skull fractures but do nothing to stop sheer forces on the brain as the head rotates. Helmet companies have all released new helmets designed to do the exact same job helmets have always done, but more efficiently, swapping out one material for another. This is like swapping out your radium water for uranium water, and ultimately getting nothing but higher prices.

The only way we can get the NFL to do the right thing is to educate each other.

It would be naive of us to expect the NFL’s heart to grow three sizes in one day. Just like any other company, the NFL is focused on making money, and implementing significant changes for the sake of safety comes with a risk of losing revenue. The best chance we have at fixing the problem is to educate each other and correct these public misconceptions, so eventually, when the commissioner and the owners do what it takes to appear as though they care, those actions will be indistinguishable from genuine efforts to save our athletes from CTE. All of us, together, can trick the NFL into doing the right thing for the wrong reasons.

About

Jason Thalken, PhD :

![]()

Jason Thalken has a PhD in computational condensed matter physics from the University of Southern California, and bachelor’s degrees in physics, mathematics, and philosophy from the University of Texas. He is the inventor on eight patent applications for data science and modeling in the financial services industry, and one patent application for protecting the brain from trauma in such sports as boxing, MMA, and football. Since 1995, Jason has studied and competed in more than eight different martial arts styles and has a black belt in Hapkido under Grand Master Ho Jin Song. Jason Thalken has spent the last fifteen years in Austin, Los Angeles, and New York City, and currently resides in Seattle, Washington, with his family. He is the author of Fight Like a Physicist: The Incredible Science Behind Martial Arts, published by YMAA Publication Center.

Jason Thalken has a PhD in computational condensed matter physics from the University of Southern California, and bachelor’s degrees in physics, mathematics, and philosophy from the University of Texas. He is the inventor on eight patent applications for data science and modeling in the financial services industry, and one patent application for protecting the brain from trauma in such sports as boxing, MMA, and football. Since 1995, Jason has studied and competed in more than eight different martial arts styles and has a black belt in Hapkido under Grand Master Ho Jin Song. Jason Thalken has spent the last fifteen years in Austin, Los Angeles, and New York City, and currently resides in Seattle, Washington, with his family. He is the author of Fight Like a Physicist: The Incredible Science Behind Martial Arts, published by YMAA Publication Center.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article