By Gene Ching and Gigi Oh

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

More and more, Tai Chi is becoming the banner bearer for Chinese martial arts. While Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Crouching Tigers and Kung Fu Pandas have garnered the spotlight on the silver screen, Tai Chi has quietly crept down, snaking its way into colleges, hospitals, senior centers and public parks across America. Indeed, the grassroots nature of Tai Chi makes it difficult to calculate the magnitude of its spread. Unlike other martial arts, Tai Chi has a larger community outside of brick-and-mortar schools and the tournament circuit. This substratal population is difficult to tabulate.

More and more, Tai Chi is becoming the banner bearer for Chinese martial arts. While Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Crouching Tigers and Kung Fu Pandas have garnered the spotlight on the silver screen, Tai Chi has quietly crept down, snaking its way into colleges, hospitals, senior centers and public parks across America. Indeed, the grassroots nature of Tai Chi makes it difficult to calculate the magnitude of its spread. Unlike other martial arts, Tai Chi has a larger community outside of brick-and-mortar schools and the tournament circuit. This substratal population is difficult to tabulate.

So it’s not at all surprising that Tai Chi has been rising to the forefront of China’s efforts to promote her martial legacy. Tai Chi portrays the Chinese face exactly how the Chinese want to be seen – it is an elegant, time-honored and sophisticated art of peace, an art that cultivates tremendous power. Tai Chi has been one of the primary divisions in China’s heavily promoted sport of Modern Wushu. And now, a major push to renovate the international Tai Chi competition rules is underway with hopes to expand its influence even further.

Tai Chi, or Taijiquan (Grand Ultimate Boxing 太極 拳) as it is more formally called in Mandarin (Taiji for short), is foremost among the internal arts. After Modern Wushu failed to get into the Beijing Olympics in 2008, China began slowly shifting towards more internal arts like Taiji. Internal arts, or neijia (internal family 內家), makes up a category of disciplines that emphasize softness over hardness and the cultivation of internal power, the fundamental principles of Chinese Daoism. Some scholars are now theorizing that the original notion behind internal arts actually referred to styles indigenous to China. Daoist-based martial arts like Taiji are completely of Chinese origin. Buddhistderived arts like Shaolin are foreign because Buddhism originated in India, and thus these styles are “external.” However, any practitioner of internal arts knows that there is a palpable difference between internal and external practices far beyond their geographic origin. There is something to be said for internal power, even if its exact definition is elusive and esoteric.

Internal arts need not be martial. Akin to Taiji, Qigong emphasizes personal qi cultivation. However, unlike Taiji, Qigong is not necessarily martial. While there are martial forms or Qigong, most forms of Qigong are simply health-promoting with no applications to combat. This actually is what most American practitioners are looking for with Taiji – stress relief, exercise and meditation. The martial applications are superfluous in a rehab center or an old folks’ home. Alongside China’s post-Olympic promotion of internal arts, it formed the International Health Qigong Association (IHQA), which established a system for competition and ranking, along with standardized forms for Qigong practice. However, while the IHQA continues to advance today, the notion of Qigong competition never sat well with many practitioners. Qigong is contemplative not competitive, so the Qigong tournaments were somewhat ill-conceived. Furthermore, Qigong is more abstract than Taiji and far less recognized within the international vernacular. The concept of qi circulation is often viewed as too mystical. Qi is a uniquely Chinese concept that doesn’t translate very well. In Qigong, qi is usually translated as vital breath, but it can literally mean gas, air, smell, weather, or even to get angry (氣).

Recently, the International Wushu Federation (IWuF) declared that it would be expanding the internal styles within the sport of Modern Wushu by adding divisions for Xingyiquan (Form Will Boxing 形意 拳) and Baguazhang (Eight Trigram Palm 八卦 掌). Neither of these styles are very well known outside the Chinese martial arts, but when combined with Taiji, they form the trinity of internal martial arts. Professor Lin Jianhua (林建華) is a leading scholar of Chinese martial arts and a notable master of Xingyi. “Taiji is about fangfa (method 方法),” he comments in Mandarin. “Bagua is about shenfa (body methods 身法) and Xingyi is about li (power 力).” It was Xingyi’s power emission, or fajin (發勁), that attracted Professor Lin to the practice. “Xingyi fajin is very unique,” he asserts. “Chen style Taiji fajin is stationary while Xingyi fajin is moving.”

The Cultural Revolution Generation

Professor Lin was born abroad in Indonesia in 1953, but his family returned to China the following year. They settled in Zhangzhou city in the southern province of Fujian. Fujian is renowned for its martial arts, a bastion of southern folk styles. Lin’s father practiced a southern folk style called Five Beasts (wushou 五兽). Akin to the classic southern Five Animals (wuxing 五 形 – literally “five form,” same xing as in xingyi), Five Beasts deploys techniques that emulate the dragon, tiger, snake and panther, but swaps the classical crane with the eagle. Although his father practiced Kung Fu, he didn’t encourage Lin to follow. His dad believed that the new era of Communism made the nation safe and that martial arts were no longer necessary for self-protection. But Lin loved martial arts and, at age eleven, got his father’s blessing to study. Lin’s first teacher was Bao Guanfang (鲍冠芳), a famous teacher from the Zhongyang Guoshuguan (中央国术馆) who fought against the Japanese occupation in Shanghai. Lin studied three archetypal Kung Fu forms: Twelveroad Tantui (十二路彈腿), Lianbuquan (連步拳), and Dahongquan (大洪拳).

Unfortunately, the Cultural Revolution stalled Lin’s training. He had only learned Kung Fu for a few years before he was sent away to work on the farms in 1969. “Life was very hard. I had to work ten hours a day, 300 days a year. In Fujian, all of the farming fields were in the mountains. I had to walk barefoot for an hour just to get to the fields, pulling heavy carts up and down the mountains. It was a narrow road. If two oxen passed each other, they often fought. It was very dangerous, especially when it rained.” Lin is tall for a southern Chinese, standing about 5’ 9”. Being the tallest, he had to work the hardest. “I intimidated many farmers because I could carry a 200-pound rice sack through the mud. I credit my strength to my Tantui training.” Lin worked as a farmer for four years until the Cultural Revolution subsided.

In 1973, Lin was accepted to Fujian Normal University. Across China, schools were being opened and re-opened. His reputation as a hard worker helped him get in. “I went from Hell to Heaven. I was so thirsty for knowledge. I never stopped training. I trained every day and still do.” But still, university life was challenging. He was only provided with a stipend of 10 renminbi a month (about a dollar and a half at today’s conversion rate, less back in the early ‘70s), so he had to work an extra two hours every day before breakfast, just to make ends meet. Nevertheless, Fujian Normal University had a program for martial arts under the direction of Professors Guo Minghua (郭鸣 华), Lin Jinde (林锦德), and Hu Jinhuan (胡金焕). After graduating, Lin stayed on there to teach. He served as the university’s martial arts teacher from 1978 to 1983.

Then in 1979, Lin participated in New China’s first martial arts teachers’ training program at the Wuhan University of Physical Education. After the Cultural Revolution, the universities made an effort to recover and preserve the Chinese martial arts, so they gathered the nation’s leading martial arts masters and the next generation of teachers for a four-month intensive program. Leading the program were two of the most famous martial scholars of that time, Professor Wen Jingmin (温敬敏) and Professor Liu Yuhua (刘玉华). Lin was invited to represent Fujian Normal University. The program introduced Lin to Xingyi, as well as Taiji, Bagua, Fanziquan (翻子拳), and assorted weapon methods like sword and staff. Professor Wen took a liking to Lin, and gave him special tips on how to change from his previous external long fist methods to the internal art of Xingyi.

The Elements of Xingyi

Like Taiji, Xingyi is imbued with Chinese culture and Daoist theory. Legend traces its origins to the celebrated Song Dynasty General Yue Fei (1103–1142 CE 岳飛) although today most scholars believe this is an apocryphal tale. Unlike most Chinese martial arts, Xingyi doesn’t rely heavily upon horse stance (馬 步) or bow stance (弓步). Instead, it is based on a very practical fighting stance called santishi (three body power 三體勢). Xingyi is built on an arsenal of five fist techniques that map directly onto the five elements of Chinese cosmology: pi (chopping, associated with metal 劈), zuan (drilling, associated with water 钻), beng (crushing, associated with wood 崩), pao (exploding, associated with fire 炮), and heng (crossing, associated with earth 橫). There are also animal styles, typically ten animals but sometimes twelve, depending upon which lineage of Xingyi it is. There are also some weapons, predominantly spear and sword, and several partner sparring forms, or duilian (对练).

After Professor Wen’s introduction, Lin became passionate about Xingyi. “When I practiced, I got so into it, I didn’t know when to stop. My body was numb. My body could take that back then because I was young.” Lin undertook a quest to study Xingyi from China’s leading exponents. His next instructor was Professor Zhou Yongxiang (周永祥) of Jinan Normal University in Shandong. Professor Zhou, along with his brother Zhou Yonfu (周永福), were so renowned for their martial arts skills that they were known as the “two Zhous (er Zhou 二周).” Lin studied Xingyi duilian, specifically Shishouyi (拾手艺), Sanshoupao (散手炮), and the standard Anshanpao (安身炮). He sparred a lot with Zhou’s disciple, Jiang Zhoucun (姜周存), who was even taller than Li. “Zhou Yonfu is still alive. He’s now 104. His brother passed away in 2004.”

Lin’s next teacher was Wang Jingchun (王景春), a famous master from Henan who taught the Guomindang (國民黨) and was known for his flying dart (feibiao飞镖) and iron fan (tieshan 铁扇). Wang was one of the lead demonstrators at China’s Folk Martial Arts Exhibition in 1957 and was a good friend of noted Ziranmen (自然门) Master Wan Laisheng (万赖声). “At age sixty, Master Wang could strike a big tree with his snake Xingyi shoulder technique and make it shake. Henan Xingyi has only ten animals, not twelve. It’s more like the original style. Henan Xingyi has different shenfa. I still cannot match the shenfa of that older generation. Master Wang’s transition from stillness to fajin was like lightning.” Lin also learned Wang’s iron fan. “I still have his fan. It’s made of steel and weighs six pounds. It can also shoot a dart. Wang’s iron fan is very different from the fan you see practiced today. His was all combat. Each movement hits you and the strikes keep moving up the arm to the throat. Today, martial arts fan is like the fly whisk (fuchen 拂 尘). It doesn’t look like a weapon anymore. It’s just for dusting.” Lin followed Wang from 1981 until 2005 when Wang passed away.

Lin also studied with several leading Xingyi masters: Professor Kang Shaoyuan (康绍远), President of Wushu Association of Jilin, He Fusheng (何福生), President of Wushu Association of Yunnan, and Zhang Tong (张彤), a famous expert from Shanxi. “I followed He Fusheng since 1985. He was retired but invited me to study under him. He taught me Shierhengchui (twelve crossing hammer 十二横锤) and Bagua Taiji. Kang was associated with the Zhongyang Guoshuguan and Dongbei Normal University in 1998. We compiled teaching materials for the university together. He passed away in 1998 at age 89.”

Professor Lin just retired from a position at Xiamen University, considered among the top twenty universities in China today. He has taught there since 1983. Over his academic career, Lin has authored over half a dozen books by himself and collaborated with various other scholars on many others. Last year, he published an authoritative book on the history of martial arts in Fujian, the result of a decade of research, and at the end of this year he will publish another book on the subject of who’s who in the Fujian martial arts world. Lin developed a distinctive Qigong method based on Xingyi called Xingyi Yanshengong (形意养生功). China declared this new system one of the Ten Best Health Methods for Mankind, and it has a growing following in Australia and Japan. Japan has already integrated the program on the college level.

Changing the Games

Today, Professor Lin remains an International Level Judge for Modern Wushu, as well as a Vice-President of the Fujian Martial Arts Association. He holds an 8th duan degree (duan is the International ranking system for Chinese martial arts 段) and is a likely candidate for the highest level, 9th duan, when the next round of promotions occur. But as one of the world’s leading proponents of both Taiji and Xingyi, he is surprisingly out of the loop with the new developments in Modern Wushu. “The new Xingyi rules for Modern Wushu? I’m not involved in it,” Lin says diplomatically. “As a martial arts teacher, I’m not involved in the sport so much now. I’m just a judge.” Despite the imminent launching of Xingyi as a Modern Wushu division, Lin has yet to see the new Xingyi rules or teaching materials. “It should be ready now,” he says hopefully.

Lin has seen the new rules for Taiji international competition. These rules were just released prior to his interview. “The Taiji rules have changed dramatically. I just reviewed them and wonder how they will be disseminated in time. The First World Taiji Championship is scheduled for this year [IWuF has scheduled the First World Taiji Championship for November 1–4, 2014, in Chengdu, China].”

There seems to be a growing disconnect within the Wushu associations in China. It is a problem that Professor Lin recognizes but believes will improve soon as more attention is brought to the matter. Not only are these new rules being implemented with minimal preparation time for coaches, athletes and judges, the duan ranking system is becoming separated. Originally, the nine-level duan ranking system was predominantly centered on Modern Wushu. But a few years ago, the lower six duan were separated into about two dozen subdivisions by style. This means that for the first six levels, Xingyi promoted its duan holders within its own community, and every other style – Taiji, Bagua, and all of the rest – did the same. The folk grandmasters within the style were reviewed and grandfathered into the program. Now everyone must take exams. The requirements for advancement in Xingyi duan rank have become very specific. This is starting to shut out the elder folk masters, who have no interest in learning the new standardized forms. So in the past, the national governing body has not been well connected with the provincial level advancement. This is reflected in a breakdown in the duan system and is jamming promotion. “Lately, there have been orders from the top to re-establish those connections,” says Lin optimistically, “so I think things will improve soon.”

Despite the curious delays in sharing new rules and organizing the hierarchy, China remains stalwart in her efforts to promote the internal arts to the world. However cumbersome the plans for organization and promotion might be, China’s aspirations for internal styles like Taiji, Xingyi and Bagua are laudable. These internal styles bring far more than just self-defense methods typical of most martial arts. And they convey thousands of years of Chinese culture (as if that wasn’t enough). The internal arts offer a potential panacea for ailments of the modern world. No matter how much bureaucracy slows progress, if the internal arts can truly live up to their promise, they will prevail.

| Discuss this article online | |

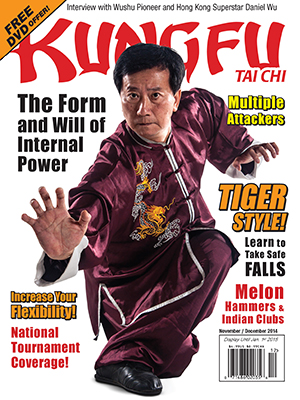

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine November+December 2014 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2014 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Gene Ching and Gigi Oh :

Professor Lin Jianhua can be contacted at Xiamen University,

Physical Education Department, 422 Siming South Road,

Xiamen, PRC postcode: 361005 xmuljh7780@163.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article