By Gene Ching

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

The San Francisco Bay Area holds the richest community for Chinese martial arts in America. The Chinese call it Jiujinshan (old gold mountain 旧金山). Believing it the "Land of Plenty", more Chinese immigrated to SF than anywhere else in the nation and still do, carrying with them the bounty of China’s martial legacies. The region is overrun with Chinese martial arts schools, so many that some are only a block away from each other. Within just a dozen miles of the Kung Fu Tai Chi Headquarters, located in SF’s East Bay, a dozen different Chinese martial arts schools are in business. That’s just Chinese martial arts schools. There are easily a dozen more schools in the same twelve-mile radius that promote different martial arts styles.

The San Francisco Bay Area holds the richest community for Chinese martial arts in America. The Chinese call it Jiujinshan (old gold mountain 旧金山). Believing it the "Land of Plenty", more Chinese immigrated to SF than anywhere else in the nation and still do, carrying with them the bounty of China’s martial legacies. The region is overrun with Chinese martial arts schools, so many that some are only a block away from each other. Within just a dozen miles of the Kung Fu Tai Chi Headquarters, located in SF’s East Bay, a dozen different Chinese martial arts schools are in business. That’s just Chinese martial arts schools. There are easily a dozen more schools in the same twelve-mile radius that promote different martial arts styles.

In such a densely populated field, it takes real talent to stand out. It takes verve. Here at Bay Area tournaments and demonstrations, Kungfu Dragon USA is always center stage. Under the direction of Master Yu Zhenlong (于振龍), Kungfu Dragon USA has risen to become one of the most successful and flamboyant schools in the region. Dressed in their signature demo team uniforms, silken black wrapped with a golden embroidered dragon, Master Yu’s students are as quick to grab the spotlight as they are to capture positions on the podiums. And yet, despite their flashy theatrical attire, Yu’s roots lie in that legendary refuge of austerity, the cradle of Zen, the Shaolin Temple.

No Matter How Hard the Past, You Can Always Begin Again

Critics and curmudgeons have complained about Shaolin Kung Fu performances. Most disdain their emphasis on Contemporary Wushu over Traditional Shaolin Kung Fu. Some even question why Buddhist monks would perform at all. However, public Kung Fu demonstrations have been a long-established facet of the Shaolin order. According to The Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts by Kang Gewu, Shaolin monks were doing Kung Fu shows for tourists during the reign of the Ming Emperor Wanli (1563–1620), who ascended to the throne at age 10 and reigned until his death nearly half a century later. This makes the tradition of performing Shaolin monks over a century and a half older than the United States of America.

Over the last few decades, Shaolin took the show on the road. In the eighties, Shaolin struggled to rebuild itself in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, restoring the temple halls and reconstructing their Kung Fu. By the nineties, that effort was rewarded with massive economic growth for Shaolin, especially as a tourist commodity. Shaolin monks did all sorts of live theatrical performances all around the globe including touring alongside rock bands at the Lollapalooza concert festival. They even appeared on Late Night with David Letterman.

However, scandalous Shaolin shows besmirched the Temple’s reputation. The Shaolin tours got so popular that fake monk tours were prevalent. Troupes of Contemporary Wushu athletes shaved their heads and donned robes to put on shows under the Shaolin banner. Some were from unscrupulous private schools from nearby Shaolin. Others weren’t even from Shaolin. The rise of biaoyanseng (show performer monks 表演僧) became so rampant that Shaolin had to take legal action to shut down fake tours. In the S.F. Bay Area, multiple "Shaolin" monk shows came through, sometimes at the same time, competing for their audience share. This came to a head in 1999, when the Venerable Shi Yongxin (释永信) was installed as the Abbot of Shaolin Temple. Among his early acts as Abbot, Yongxin worked to stop the phony Shaolin performing shows.

Master Yu was a travelling performer of Shaolin Kung Fu before immigrating to the U.S. He travelled across Asia and North America doing Kung Fu demonstrations. His experience as a Kung Fu showman is one of the reasons why his school puts on such spectacular performances. But Yu’s initial reason for going to Shaolin was the most time-honored of them all – revenge.

Don’t Waste Your Time On Revenge. Those Who Hurt You Will Eventually Face Their Own Karma.

Master Yu was born in 1989 in Puyang, a city in northeastern Henan Province about 200 miles from Shaolin. It was during the middle of China’s One-Child Policy, which began in 1979 and was upheld until fairly recently – 2015. The Policy was an attempt to curb China’s exploding population; families were restricted to only one child. However, out in Puyang, it wasn’t enforced. “Six children,” says Yu proudly. “In my area, everyone has that many people. So they think the more people you have, your family can be stronger. So I had three sisters, two older brothers. I’m the youngest one. So that’s why in the preschool time, no one can bully me because my family, we have six. Everyone else probably have three or four. So I start bullying everybody because I can. If anybody try bully me, I go to my brother, my sister. We got more people. But later on, slowly, they grow up, go on to another school, not the same school anymore. So I’m alone. I start same school, same time, with my sister because nobody watch me. My mom had to make the money for living, for six kids. So I was at preschool with my sister, one year younger, like day-care. You cannot focus. There’s no kindergarten at that time so just playing. Teacher said, ‘You’re just here for babysitting.’ So I just fighting a lot.”

But eventually, his sister moved up too and Yu was left alone. Those numbers changed to his disadvantage. One of the kids he bullied gathered up his family and got their revenge. “See my face scars?” For a distance, they aren’t obvious, but close examination reveals a snarl of scars across Yu’s face. “They scratch me. I say, ‘Wow. My goodness.’ Nobody fight me like this before." It was a wake-up call for the young boy, a hard lesson on bullying that he's carried on his face ever since.

"I say, ‘You know what? I want revenge. I want to fight back.’ So that’s when I start learning Kung Fu.”

At first, Yu’s mother suggested Shaolin Temple because his aunt was good friends with one of the prominent monks there, Shi Guosong (释果松). But it was far away and Yu was still very young, so they decided to start at a school in the city. Yu trained there for six months and his teacher quickly spotted his potential. “He could see I could go far because I could not sit still – always climb the tree – so he think, ‘Good to go!’ And my mom talked to my aunt. My aunt talked to Guosong. So I went to the Shaolin Temple when I was six years old.”

What's Done to the Children Is Done to Society

Imagine being left alone at Shaolin Temple at age six. Yu had no idea what he was in for. “First I just went – didn’t think too much. Everything different right away. ‘Where’s my mom?’ I’m looking here and there.” Since Shaolin’s reconstruction, thousands of children live and train in the schools in Dengfeng, the small city nearest to the Temple. In 2018, there were some 60 schools in the area, with 100,000 full-time martial arts students. The Shaolin Taguo Martial Arts School (少林塔沟武术学校) boasted a student body of 30,000 students alone. When Yu arrived in 1995, these numbers were much smaller; however, they were still staggering compared to any other martial community anywhere else in the world. In Dengfeng where everyone is Kung Fu fighting for real, it's more than just a little bit frightening. It was a very rough place for a six-year-old, regardless of his potential.

“So second day, we start training – Damo dong (Bodhidharma’s cave – situated on a mountain peak behind Shaolin Temple 達摩洞). Because I’m the shortest one in the class, they all went to the mountain, and Shifu required us to go down the stairs, you know?” Leading up to the cave is a long steep stone staircase. It was often used for training in the early morning before the tourists arrived. The most common exercise involves crawling down the stone steps in a plank position using only hands and feet. “Because my hand too weak, my hand just slide, my chest slide on to the stairs. Blood. They just put dirt on it to stop the bleeding. ‘Just keep going!’ I say, ‘Wow, these people have no heart,’” remembers Yu with a laugh.

Then his eyes grow cold with the memories. “They use a stick from the tree to whip you. Because I do have a little bit before Shaolin Temple, half year, and it [was] a little bit different in Shaolin Temple. They have bow stance – when kicking, heel don’t off the ground. I thought it was heel off the ground. I keep doing it. Shifu thought I was challenging him. He start training staff and second day I thought, ‘Oh my God. This is not what I want.’ Then I start crying. My parents are away, and I start missing home.”

Despite their warrior brutality, Shaolin monks are still Buddhist monks who do have hearts. Later, Guosong showed some compassion towards his youngest pupil. “He came over, get out the baiyao (literally 'white medicine' 白药, a common blood-clotting agent used in traditional Chinese medicine), start having a conversation. 'It's okay,' he say. ‘To have a strong mind, have a strong body first.' I think so. Well, okay, but I'm still missing home.” Young Yu stuck it out, a six-year-old boy, with no family to help him anymore. “My mom come over then she see me training later on. She say, 'You want to go home?' because my mom, tears come. Training so hard. Inside of me – hurt – but I don't want to go back. Since I chose this, I didn't want to go back. So that's why I keep up...for many years.”

Just as a Snake Sheds Its Skin, We Must Shed Our Past Over and Over Again

“We lived in Shaolin Temple, in the back of Da Xiong Bao Dian (‘Hall of Great Strength’ – a main hall in a Chinese Buddhist temple 大雄宝殿). There's other monks living there.” At that time, like many Shaolin masters, Guosong also oversaw a private school in Dengfeng where Yu also trained. However, he was mostly in the temple at first where he remembers performing for tourists, just like those monks centuries ago.

But times changed. Along with disbanding the fake Shaolin tours, Abbot Yongxin pushed all of the private schools out of the immediate Shaolin vicinity in order to restore more dignity to the Temple. Most the schools relocated to Dengfeng. This also affected non-monastics like Yu who were living in the temple at the time. “I think it started 2001 – everyone start moving out. From that time, we moving out too – from the Shaolin Temple to the Henan University. They combined it together so that's where I started learning a little bit [of] modern.”

Aside from his Shifu Guosong, Yu had already studied with another noted Shaolin master, Coach Jin Pengwei (金鹏伟); but moving to the University introduced him to the showiest form of Chinese martial arts, the sport of Contemporary Wushu. It was a whole new world, especially then because a new scoring system was being introduced. Loosely modeled after gymnastics, international competition was judged on difficulty movements or nandu (難度). “From 13, coming out from Shaolin Temple, my Shifu sent like four people went to learn contemporary in the Henan team. That's when the difficulty [nandu] first started – so 2003. We start early so we had to learn how to do spinning. Before it's hard, right? How to do traditional – who's better score? You cannot tell. You only see the power. But later on, the government released some difficulties like gymnastic so that way easier to adjust who getting more points. So then they start having a new system coming out – the difficulty like jumping outside kicks. I was one of them to learn at the start. The contemporary.” Nandu was officially introduced to Contemporary Wushu after the 2003 World Wushu Games in Macau.

Encountering a Tiger

Encountering a Tiger

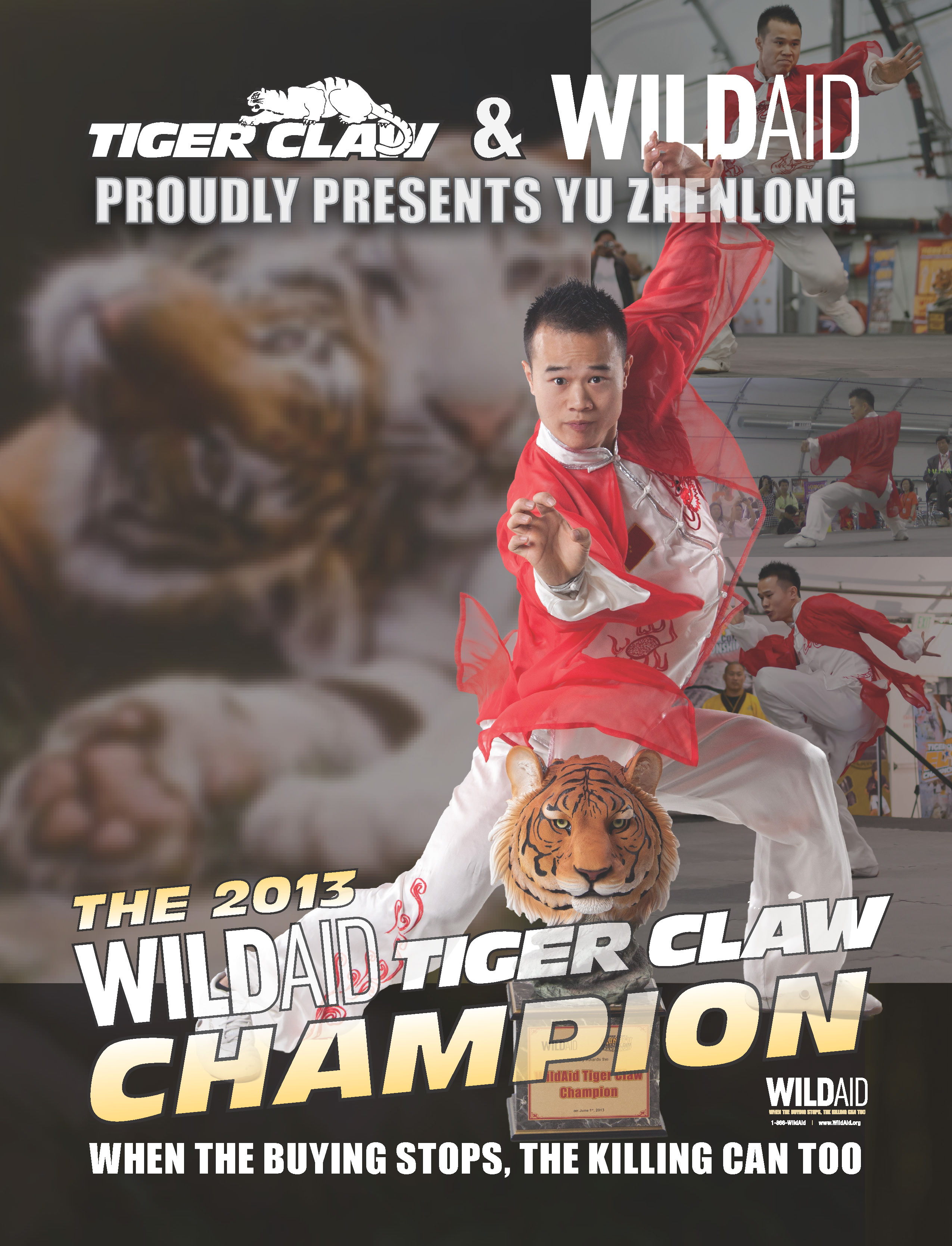

Master Yu would not have gotten as far as he has without achieving a solid competitive record. As a youth, he won titles on the provincial and national level in the late nineties and placed as an adult in Hong Kong and at the renowned 2004 World Traditional Kung Fu Festival in Zhengzhou near Shaolin. When he first immigrated to California, he captured titles in some local championships including the most high-profile showcase event at the Tiger Claw Elite Championships – the WildAid Tiger Claw title. In 2013, he won the fourth WildAid Tiger Claw Championship, the charity division under the auspices of the Tiger Claw Foundation. All proceeds of the WildAid Tiger Claw Championship are donated to WildAid, a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of endangered species in the wild. Not only do champions get spotlighted in Kung Fu Tai Chi, they get good karma knowing that just by competing in this unique division, they are helping the world.

Since then, Yu’s Kungfu Dragon USA has dominated WildAid Tiger Claw Championship more than any other school. In 2015, Kungfu Dragon students captured both newly established youth divisions. Leland Zhang won the Teen Tiger (12–17) and Ian Lim won the Tiger Cub (11 & under). The following year, Lim returned as a teenager to win the Teen Tiger. In 2017 Max Lwin captured the Tiger Cub title (Lwin also took the Top Dog Championship, a special showcase division exclusively for Dog Style Kung Fu for Year of the Dog in 2018). And in 2018, one of the coaches of Kungfu Dragon USA, Fan Lei, won the coveted adult title. Given the any form, any style format of the WildAid Tiger Claw Championship, Contemporary Wushu prevails on the podium. Having both traditional Shaolin and contemporary Wushu in his arsenal allows Master Yu to meet his students’ needs and groom them appropriately. “I'm not like Fan Lei, last year's Tiger Claw WildAid champion. He's professional. I just did Wushu, so I know. And I think it's a beautiful art. But for our school, everyone either way – do the contemporary or traditional. Both are good so why not?”

This combined approach mirrors that of most of the Dengfeng schools and is arguably one of the reasons Shaolin has been able to thrive. It’s the secret ingredient that makes Kungfu Dragon USA’s performances so spicy. “When we go to performance, we have a different kind of style. That's why we have a lot of performance. People see the contemporary – look beautiful. Traditional you have the different flavor mixed together so the performance looking different. It will appear traditional – you know, Shaolin fist, Dahong fist (大洪拳). We looking good when people understand what we are doing. People don't understand, they say, 'Okay. They just do something.' But contemporary, 'Wow! They're beautiful!' Then they look again. So now we have to combine them together. But that's only for the team. Regular class we have only traditional. Every year we have the team selection. So the kids – if they are flexible, we pull them to Youth Team. And some to Team B, or Adult Team. The people doing Adult Team, some of them getting grand champion from Tiger Claw Elite. That's our ticket to achieving like that. We build a system like that way – traditional, self-defense, only traditional Dahong fist and Tongbi fist (通臂拳) – all those traditional combined with the self-defense – Chinese boxing.

It Is Better to Conquer Yourself, Than to Win a Thousand Battles

While some practitioners are divisive when it comes to traditional and contemporary, Master Yu strives to strike a balance within his school. And yet, on stage, he favors the spectacle, and Contemporary Wushu is fundamentally more spectacular. Stage performances are intrinsically distinct from combat. Even when demonstrating applications, it must be staged for stage, and that can lack audience appeal. "Even in China, this become a problem too. UFC, they have tournament for that. Chinese Sanshou (free sparring 散手) – they have a tournament for that. What am I going to show you? Application, right? If you set up, you have to set up. Okay, do blocking, take down, oh you got set up. You don't do that real fighting, grab hair – liability. And that's just one way of promoting culture behind it. You can show tradition – that so boring. That's why you do fancy things. People say 'Woah!'

"But behind there in regular class time, we teach application, self defense, Chinese boxing, take down catches. This thing is very hard to show it. Even show it, people think that's boring. In term of sport too, we are promoting as a sport. Application – we put them in a separate part with that. Adult team – we want to show them more. Their performance form is like application for a soldier, like catching, take down, combination of that. It's not so much showing like Wushu performance style – little bit different.

“Different backgrounds, we see different needs, for kids practice, for business, for adults. Also we notice if people just practice, practice, they lost interest very soon, so it's for business wise and for the individual. For business wise, if they're not on the team after one or two years, they're going to quit. If they're on the team, they can learn more than the regular class. They can keep up for many years. They can show the performance, and also, most important, they can get over their shyness. They can be able to show who they are. All the kid love it. People clapping for them. They feel good for themselves. And also, we can show our skill, show our art – Chinese Shaolin Kung Fu to the world.”

When Watching After Others, You Watch After Yourself

"Since we're going to represent Chinese culture and Kung Fu, we don't want to just go there. We want to make sure we're doing the right thing for that." Kungfu Dragon USA takes performances very seriously, one of many reasons why their demo team is in high demand at local community events and festivals, many outside the martial arts tournaments. Yu plans their shows strategically and methodically, like a general maps out a military campaign. There are rehearsals, call times, catering their show to their audiences.

“We have four different teams – Youth Team, start with Tongzigong (童子功); Adult Team, more traditional, Team B basically combine traditional and contemporary together. And Team A is basically selecting from the other 3 teams – whoever doing better in tournament, then we pull them out like that. That's why we have good performances. We have traditional going out representing application. We have Youth Team making Tongzigong like that, like fun. We have Team B come out – nunchuks – we have discipline. We have Team A with the skill. So that's why each team is different, so all the audience see different things. We can manage based on the stage, based on the audience, based on what they need, we can do different things.”

Those Who Cling to Perceptions and Views Wander the World Offending People

Nunchuks. Nothing raises a traditional Kung Fu curmudgeon's eyebrow like Kung Fu nunchuks. Bruce Lee made Nunchaku famous, forever binding them with Kung Fu, even though they are weapons of Okinawan origin. Audiences expect them at martial arts demos. They don't distinguish between Chinese and Okinawan traditions. Traditionalists find them inauthentic. There is a traditional form of Chinese flails akin to nunchaku called erjiegun (two-section staff 二節棍), but the shafts are long. Yu is quick to confess that that's not what he teachers. “Not traditional style, performance style. Shaolin fist, Tongbi fist, you have, but nunchuks, even Shaolin temple doesn't have a lot. That's very traditional, like minjian (folk style 民间), like Xinyiba (literally ‘heart thought guard’ an esoteric secular style of Shaolin Kung Fu 心意把). It's very rare.”

Adopting nunchaku as a performance weapon is one of Yu's concessions to showmanship. And yet, at the same time, he doesn't exaggerate his Shaolin foundation on stage. Unlike those fake Shaolin tours, his school doesn't don monk robes. Naive spectators wouldn't even know that his students do Shaolin Kung Fu unless they can recognize the traditional forms. Most of the graduates of Shaolin Temple, especially those who were on performance teams, really milk their Shaolin connection. Their school uniforms are monk robes and they go by their Shaolin names over their given names (Shaolin disciples are given a special lineage name when they take their vows). However, Master Yu is clear about not being indoctrinated. “No I didn't. Just performance. I didn't take the vows for that.”

Yu follows Buddhism but not to the extent of a monastic, and that figures into his choice not to have his students wear monk robes. He wore them while on Shaolin Temple demonstration tours but not anymore. “Before, I was in the performance team. But now, because I'm not fully understanding the Buddhism, it's really different for performance than if you wear them for class all the time. I don't feel like I've earned that respect yet, so I feel like I need to be working harder to be like that every day. That's just me personally like that.

“Since we're don't teaching Buddhism, you just look at yourself. For me, there's a lot of respect in there. I think that there's culture behind there. Behind there is the Buddhism. It's respect to me. Why just go here, wear like that? You got to get inside there, behind culture, behind the Buddhism, not just, 'Oh, I'm a student. I can wear this.'

What You Think, You Become

Shaolin Kung Fu has come a long way in the last half century, along with the times. Master Yu Zhenlong is one of many Shaolin ambassadors, bearing its ponderous legacy. And yet, unlike so many monk-robed masters, he is bringing Shaolin beyond its religious trappings and adapting to the contemporary. “Our goal is a little bit different because we see different types.” So-called traditionalists might find fault, but Master Yu is unperturbed. He continues to train his pupils, polish more trophies and book his next school performance.

| Discuss this article online | |

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine - Winter 2020 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2020 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Gene Ching :

For more about Master Yu Zhenlong, visit his Kungfu Dragon USA school website at kungfudragonusa.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article