By Gene Ching and Gigi Oh

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

Everyone is buzzing about China’s film market. Second only to the United States now, China’s insatiable appetite for movies reflects her expanding middle class and her rise as a first-world nation. Movie theaters are sprouting up there at an alarming rate, and major Hollywood franchises like James Bond, Avengers and Transformers have all migrated eastward to court the world’s largest population.

Everyone is buzzing about China’s film market. Second only to the United States now, China’s insatiable appetite for movies reflects her expanding middle class and her rise as a first-world nation. Movie theaters are sprouting up there at an alarming rate, and major Hollywood franchises like James Bond, Avengers and Transformers have all migrated eastward to court the world’s largest population.

Meanwhile, China continues to reel out its own movies in hopes of gaining global cinematic “face.” If China succeeds in making a worldwide blockbuster, the impact might be a windfall, a telling barometer of global standing. What’s more, if they hit with a martial arts film, it would be a tremendous boon for the martial industry. Nothing grabs the public eye more than a blockbuster film. A popular martial arts film would bring a horde of new students scurrying to enroll.

Hollywood blockbusters have dwelt upon comic superheroes lately, mostly due to advancements in special effects. Spectacle precedes story. Similarly on the other side of the Pacific, a subgenre of China’s martial arts films has grown stunningly epic. Dubbed Fant-Asia, films based on Chinese myth have always been a mainstay with Chinese film. Fant-Asia films enjoyed a surge in popularity in the late ‘80s that lasted nearly a decade. Director Tsui Hark led the Fant-Asia field with his visionary films like Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), The Swordsman (1990), and Green Snake (1993). Although their special effects are dated today, these films are still charming and imaginative. Categorized as wuxia (martial knight 武俠), these films recount immortal tales of sword and sorcery, fox demons and hidden treasures, magic curses and unrequited love, tales of the jianghu (江湖), which literally means “rivers and lakes” but colloquially refers to the community of martial arts masters, knights and villains.

Fant-Asia cinema is enjoying a resurgence, now super-charged with modern CGI effects and 3D. Leading the charge are films like Tsui Hark’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2012 龍門飛甲), China’s first major 3D effort with Jet Li, and Wuershan’s Painted Skin: The Resurrection (2012 畫皮Ⅱ), also in 3D, starring the bewitching beauties Vicky Zhao Wei and Zhou Xun. The latest 3D Fant-Asia film is the lugubriously titled The White Haired Witch of Lunar Kingdom (白发魔女传之明月天国) starring Fan Bingbing. Hollywood may soon know Fan, as she will also be appearing in the upcoming X-Men: Days of Future Past. The White Haired Witch of Lunar Kingdom is based on a popular fantasy serial titled Baifa Monu Zhuan (白髮魔女傳) by Liang Yusheng (1926-2009 梁羽生). The tale has already been made into four films, including Ronny Yu’s visionary Fant-Asia flick The Bride with White Hair (1993 白髮魔女傳). The White Witch was also played by Li Bingbing (not to be confused with Fan) in the 2008 Hollywood film The Forbidden Kingdom starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li. Apart from being major Chinese blockbusters, Flying Swords, Painted Skin and The White Haired Witch have another thing in common. Starring in all of them is one of China’s greatest Wushu champions, a rival of Jet Li, and the creator of drunken cudgel, Master Sun Jiankui (孫建魁).

First Generation Champion of Modern Wushu

“No, I never thought about being an actor,” confesses Master Sun in Mandarin. “It was more like fate.” In person, Sun conceals his star qualities with an attitude of casual modesty. Even with his resonant deep voice and striking eyebrows, he could go unnoticed in public despite his stardom. Only his sharply erect posture and the occasional flash of lightning quick reflexes might betray his martial background. Sun was one of the first generation of Wushu champions who often shared the winner’s podium with Jet Li.

Since its inception, traditionalists have been critical of Modern Wushu for its floweriness and its ineffectiveness for real combat. However, this condemnation cannot be directed at Wushu’s first generation. The first-gen athletes were well-rooted in traditional Kung Fu because that’s all there was at the time. The sport of Modern Wushu sprouted from traditional styles, which was where Master Sun had his start.

A native of Shandong Province, Sun started learning at age eight from his father, who, like many from that region, was a Mantis Kung Fu enthusiast. His father was studying Mantis (tanglang 螳螂) under Zhu Yusheng (祝玉笙) as well as his martial brother, Sun Yujun (孫玉君). Sun Yujun was a practitioner of many styles, once the youngest at the Qingdao Guoshuguan (青岛國術館), and a renowned fighter. Sun Jiankui studied with his dad for about two years. Then his dad was called away for work, so he was taken to study under Master Sun Yujun. But by then, the master wasn’t taking younger students, so he passed him to another teacher, Zhang Ruixuan (張瑞萱). Zhang was a provincial champion and a friend of Grandmaster Yu Chenghui (Cover Master July+August 2012 于承惠). Sun trained with Zhang for about a year and a half. His talent and discipline shined and he soon was training with the provincial team himself.

Master Sun focused on jian (straight sword 劍) and qiang (spear 槍); however, Modern Wushu competition was much different back then in the late ‘60s. Today, an athlete might specialize in a single division, but back in Sun’s day, more breadth was required. “Taiji, Tanglang, Fanzi, Tongbei, we were separated into categories. Each competitor had to do six forms: zixue (self-selected 自选), a long and a short weapon, plus the national competition routines for empty hand and weapon, and duilian (sparring set 对练). Sometimes we had to compete in jiti (group synchronized forms 集体) too.” Also in those early days, champions were awarded levels instead of a single gold, silver and bronze. Communism rejects competition so no winner was openly declared. Instead, all competitors who achieved a certain criteria score were placed into first level, then second, then third. It was a thinly guised device to work around Chicom ideology. While it has been discarded for major competitions today, it persists in some international friendship tournaments, allowing a large number of athletes visiting China to return home with first level “gold” medals.

Sun’s prime competitive years were in the seventies, a golden era for the first generation of Modern Wushu. Sun remembers it nostalgically. “In 1974, I went to Xian and won 6th place for nandao (southern broadsword 南刀). In Harbin in ’76, our Shandong team placed first. In ’77, I placed 3rd in dao (broadsword 刀) in Inner Mongolia. I had changed to dao when I got on the Shandong team. At the Nationals in ’78 in Hunan, Jet Li placed first, I placed second and Zhao Changjun (赵长军) placed third. It was often Jet, Zhao and me on the podium. I competed against Jet a lot. We’re very good friends.” By age thirteen, Sun was scouted for the National Team from the Shandong Provincial Team. But after 1979, there was a shift in how Modern Wushu operated and Sun stepped down. He was no longer placing in the top three, mostly taking fourth place. “I always did well in the pre-game events. I had the highest score. But for some reason,” says Sun with a knowing nod, “that never transferred to the final scores.” His final competition was in 1983.

The Shaolin Temple Trilogy and the Creation of Drunken Staff

In the ‘80s, Sun Jiankui was cast alongside Jet Li, Yu Chenghui and Yu Hai (Cover Master January+February 2007 于海) in the groundbreaking film, Shaolin Temple (1982 少林寺). Filmed at the original Shaolin Temple on Songshan, this film was a major blockbuster inspiring a generation of martial artists and was even instrumental in the restoration of Shaolin Temple. What’s more, it established some new forms into the curriculum in the Shaolin area and beyond. Yu Hai’s unique mantis form became a mainstay for both traditional Kung Fu and Modern Wushu practitioners. Contemporary toad style, while it might have some basis in history, can be attributed to a comedic scene from this film. And most significantly, modern drunken staff emerged, a direct result of Master Sun’s involvement with the film.

“I was originally cast in a minor role.” All of the actors were assembled for training for a month before the shoot started. It was during that period that Sun managed to catch the eyes of the filmmakers. “When filming began, Director Cheung Sing Yim (张鑫炎) often told us that we had to make up a fight scene just a day before we shot it. I didn’t really know staff, but I had to pick it up quickly because it was Shaolin and Shaolin is famous for staff. I just made up the drunken staff routine you see in the movie. It wasn’t popular before the film.”

Shaolin Temple spawned two thematic sequels. Although the storylines used different characters, they were also shot at Shaolin Temple and reunited the ensemble cast. Beyond the Shandong representatives, the two Yus and Sun, and Jet, there were two more noted Wushu champions in all three films, Hu Jianchang (胡堅強) and Ji Chunhua (計春華) a.k.a. Baldy. In Kids from Shaolin (1984 少林小子), Sun began to show his range for character acting by playing four roles including a fake Daoist, an Indian kidnapper and a barbarian (all cross-eyed). “Production on Kids from Shaolin was slow because the director was dealing with some hard issues.” North South Shaolin (1986 南北少林) showcased the emergent southern style version of Modern Wushu. “Jet, Yu Chenghui and I often sparred with each other. Hu Jianchang and Baldy fought against each other as they were both more southern.”

Sun left the Wushu team in 1987 to make another movie that reunited all of the aforementioned Shaolin trilogy stars except for Jet. Again under the direction of Cheung Sing Yim, Yellow River Fighter (1988 黃河大俠) is a bloody tale filmed in some magnificent scenic panoramas. The film focuses on Yu Chenghui as a drunken blind swordsman, with the rest of the Shaolin ensemble actors appearing in cameo fights, except for Yu Hai, who plays a Buddhist Abbot, but never does battle. Since then, Master Sun has been in over twenty major films, sometimes acting, sometimes as a stuntman, and sometimes as a fight choreographer.

Promoting Tournaments and Shows to Wuxia Star

The nineties brought yet another career shift for Sun Jiankui. For four years, he was a promoter for an international martial arts competition in Jinan, the capital city in Shandong, the Jinan International Traditional Martial Arts Tournament. Also during that period, Sun promoted a Kung Fu demonstration show called China Shandong Shaolin Wushu Performance. It toured the world, some 120 cities for almost a decade. “I hated using the Shaolin name, but we had to for certain markets. We were connected to a duplicate temple in Poland.” From ’95 to ’99, Sun admits he donned monk robes for the shows, even though the show did not have the blessing of Shaolin Temple. The last competition was held in 2001 and both operations folded when Sun’s business partner, Fang Chunhe (范春和), had a heart attack.

During that period, Sun also appeared in another film, joining Jet Li, Yu Hai and Michelle Yeoh for Tai Chi Master a.k.a. Twin Warriors (1993 太极张三丰). In this film, directed by Yuen Woo Ping, Sun played a eunuch. But after Sun concluded his stint as a promoter, he left the non-cinematic martial arts behind. “Now I avoid those circles. I no longer want to be involved.

“Modern Wushu has to turn around, just like anything when you develop it to the limit. It has to go back to basics. It needs to remember how to fight for real, to start from the traditional again. Right now, it’s like a bottleneck that’s getting smaller and smaller. There’s no way out. So many regulations! It has lost the tradition of jingshen (essential spirit 精神), wude (martial ethics 武德) and jishu (technique 技术). People only follow fame, money, power, and the need for more trophies. But the road is coming to an end. They must turn around. Even if you have all the skills, if you don’t have wude, your martial arts is lacking.”

Sun began traveling to America to support his son who was enrolled in film school at San Francisco State University. Meanwhile, back in China, he was tapped to work in several television series. For years, Wuxia soap operas have comprised a large portion of Chinese TV programming. These are typically based on popular myths and legends just like the Fant-Asia film genre with strong elements of sword and sorcery. In 2003, Sun starred in Seven Swords, a TV version of another popular wuxia novel by Liang Yusheng, Seven Swords under Heaven Mountain (七劍下天山). This tale was also made into a film starring Donnie Yen in 2005. “There were thirty or forty episodes. I was the villain. Yu Chenghui was the top sword, the main hero. I was also the swordplay choreographer. In one scene, I fought against three of the seven swords at one time. But Yu slays me in the end.” From 2005 to 2006, Sun was the action choreographer for Bao Yu Liu Hua (暴雨梨花), a drama set in the romantic period of Shanghai in the 1920s. He also served as action choreographer on Tiandi Yunyuan Qishengyu (天地姻缘七仙女), another TV show in 2009. The show that some Westerners might recognize was The Legend of Bruce Lee (2008), as it is available via online streaming as well as DVD and Blu-Ray. This 50-episode series featured Yu Chenghui as Bruce’s teacher Ip Man and Ray Park (Darth Maul of Star Wars) as Chuck Norris. Sun played a bit part as one of the villains and also served as action choreographer for the scenes shot in the United States.

Wuxia Film Now

Flying Swords at Dragon Gate was China’s first major 3D film using today’s new technologies, an ambitious undertaking even for veteran Fant-Asia director Tsui Hark. With Jet Li in the lead role, the film enjoyed a limited international release in IMAX 3D. Domestically, it set the record for the highest-grossing Chinese film in IMAX format and received seven nominations at the Asian Film Awards, the most of any film that year (it won for Best Visual Effects and Costume Design). Sun remembers it as a very challenging film to make. “With 3D, positioning is very important. You can’t miss even a little. Precision takes a lot more time. Sometimes we couldn’t finish one movement after a whole day. You can’t be too close to the camera. It was also very cold when we filmed – -20C! – so we weren’t so flexible. Some of us couldn’t even hold our swords. Fortunately, most of my action was filmed indoors. I acted and choreographed. Usually I do both now, 50% of each.”

Painted Skin 2 was different. Directed by one of China’s hottest new talents, Wuershan, Sun was cast again as a eunuch and only acted. He didn’t do any martial arts at all. While Jet Li and Jackie Chan have struggled to get face as dramatic actors instead of just action stars, Sun has moved effortlessly into playing non-martial roles. “Wuershan was looking for someone to play a eunuch. He had heard of me and invited me over. There were four investors in that film which made things complicated.”

Sun is very excited about The White Haired Witch of Lunar Kingdom. “Director Zhang Zhiliang a.k.a. Jacob Cheung (張之亮) and Huang Xiaoming (黃曉明) are from Shandong, from Qingdao. I play one of the three Wudang elders.” After that, he has some potential projects lined up including a possible role as a bandit in another 3D period film, this one based in Northeast China in the 1920s.

“Chinese film is improving so fast – too fast. Only action films have been featured since the door opened. Hong Kong was prosperous, but not so much now. Today, Mainland China is the base. Many directors from Hollywood, France and Italy are coming to China now. It’s not only Kung Fu films, but also drama, action and war films. China has the market. Suddenly, there are 20,000 new movie theater screens in China.

“Kids today, the generation of the ‘80s and ‘90s, are more westernized. They have become fans, adoring the celebrities. But with so many investors from outside China and within, there needs to be a good system of regulation. It’s like a freefall. Within China, there are problems. Chinese stars are asking a lot of money now. How can this be controlled? It’s just not grounded. Everything is floating. It looks prosperous, but there’s no solid foundation.

“I don’t really have any advice for martial artists aspiring to be actors. If you train in the martial arts and your goal is to be an actor, that’s not quite right. With everything, you must look at the whole picture, not just one thing. There are so many ‘wrongs’ to being an actor. I don’t know how to help people make choices. I don’t know what they need. To be an actor, there are so many qualities you must have. You can’t just be pretty or just skilled in martial arts.

“The first important qualities everyone must have is renping (upstanding character 人品) and de (ethics, as in wude). If you are not a good person, you may just fall. Second is ability. You need a good value system. If you just want to be an actor, the martial arts aren’t such a good value. For me personally, with everything I tried to do, I tried my best. I never anticipated acting. You must have a good mindset. To do anything, you must think you can be the best, but you must calculate for loss too. Then, if the sky drops, the earth will catch it.”

| Discuss this article online | |

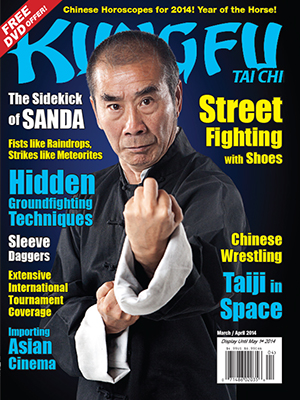

| KUNG FU TAI CHI MAGAZINE MARCH + APRIL 2014 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2014 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

Written by Gene Ching and Gigi Oh for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article