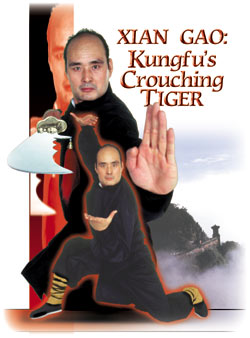

A Martial Arts Odyssey from Western China to the Set of Ang Lee

By Bob Feldman

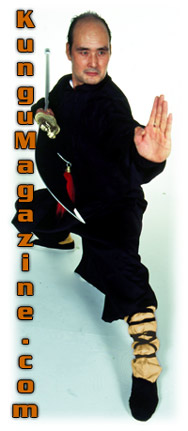

Xian Gao is a multifaceted talent. Martial artist, kungfu movie star and teacher, he also has considerable cinematic experience as a choreographer and trainer. Lately you might have seen him in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. What Gao considers most important however, is to live, think, and breath traditional Chinese martial arts.

Xian Gao is a multifaceted talent. Martial artist, kungfu movie star and teacher, he also has considerable cinematic experience as a choreographer and trainer. Lately you might have seen him in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. What Gao considers most important however, is to live, think, and breath traditional Chinese martial arts.

Gao was born in Xian city, Shanxi province, China. Shanxi has a strong tradition of martial arts for over two millennia. Xian, the provincial capital, still possesses much of the traditional architecture of China and is famous for its life-size Terracotta Warrior statues. Amidst these traditions, young Xian Gao grew up. He began to study martial arts as a youth, primarily for protection during the Cultural Revolution, when, as the son of a party official, he often had to fight to protect himself. Master Gao's training first came on the streets when he was the target of the Red Guard and street gangs. Subsequently, he sought out martial arts teachers to enhance his fighting skills.

While Gao had many teachers throughout his career, he credits four mentors with being the most influential on his development. All had humility, and all were devoted to Daoist and Confucian principles. These masters are Zho Fuli, Ma Chenda, Su Taihe, and Yu Tienpei.

Grandmasters of Shanxi

Yu Tienpei was Gao's first teacher. Master Yu specialized in Long Fist, Chaquan, Paoquan and Hongquan, as well as in animal styles. When he was younger, Gao was also drawn to Sanda -- Chinese full contact fighting, and while under the tutelage of Yu, and his second teacher Zho Fuli, a graduate of the famous national Guoshu Institute, (the preeminent government school of martial arts in China in the 20's ad 30's), Gao began to compete as a sanda fighter. After continuing his sanda studies with the national renowned teacher Ma Chenda, Gao placed second in the heavy weight division of the Shanxi open full-contact Championship, no easy feat in a province known for its Xingyiquan and other indigenous martial arts. Gao also studied Zuramen ("Natural Style") and Liuhequan from Master Zho, as well as traditional weapons including broadsword, straight sword, staff, spear, 9-section whip chain and 3-section staff.

Gao excelled as a Sanda fighter, as he was over 6 feet tall with a long reach and quick reaction skills. Subsequently he was accepted at the Xian Sports Institute where he majored in martial arts. The "Tixue" or "Sports Institute" are provincial universities specializing in sports science and teaching. At that time, there were only between 14 and 20 students per class, and the competition was keen for acceptance, as hundreds of aspiring applicants compete for each place. Master Gao later went on to get a Master's degree in Physiology and sports conditioning, which would serve him later a martial arts actor, fight choreographer and director, all while continuing his traditional training outside the university.

Gao excelled as a Sanda fighter, as he was over 6 feet tall with a long reach and quick reaction skills. Subsequently he was accepted at the Xian Sports Institute where he majored in martial arts. The "Tixue" or "Sports Institute" are provincial universities specializing in sports science and teaching. At that time, there were only between 14 and 20 students per class, and the competition was keen for acceptance, as hundreds of aspiring applicants compete for each place. Master Gao later went on to get a Master's degree in Physiology and sports conditioning, which would serve him later a martial arts actor, fight choreographer and director, all while continuing his traditional training outside the university.

While at Xian Tixue, Gao studied and competed in new Wushu and Sanshou under many famous masters that had been recruited by the government for the faculty. Gao won many modern Wushu competitions undoubtedly impressing the judges with his size, speed, gymnastic skills and athletic prowess. Perhaps because of his fighting experience and training in traditional martial arts, Gao continued to practice the old systems as he was impressed by their fighting applications and benefits for health and longevity. One of Gao's main teachers at the Institute was Master Ma Chenda, a scion of a famous martial arts family and a former national fighting champion. Master Ma was famous for his skills in Bajiquan, Fanziquan, Tongbeiquan and Piguaquan.

Baji,Fanzi, Tongbei and Piqua

Bajiquan or "Eight Extremes Boxing" is known for its explosive movements and close fighting skills. Tongbeiquan ("Through the Back Boxing") generates its power from the shoulders through long expanded arm movements and powerful chopping attacks while Piguaquan ("Axe Handle Boxing") utilizes flexible moments of the arms elbows and shoulders, quick changes between high and low postures, and a supple chest and waist. Fanziquan or ("Tumbling Boxing") is famous for its fact barrage of punches, circular movements and spiraling kicking techniques. Master Ma is still well known in China, and continues to teach. As Ma took a particular liking to Gao, he privately taught Gao his specialties: traditional Pigua, Fanzi, Baji, and Tongbei, including their fighting applications and weapons. As these sessions were usually held at Ma's home, Gao became close with Ma's sons and spent many hours with learning about traditional martial arts history, customs, and ethics from the master.

Prior to his training with Ma, Gao had focused primarily in long fist and other hard external systems. Ma's approach was somewhat different. He taught Gao the internal methods of each of these systems along with their techniques to evoke martial power. Gao particularly excelled at Tongbei, Pigua and Fanzi, as the continuous changing between low crouching and expansive open postures particularly suited his height and stature. Ma's approach was also somewhat different from what Gao has been previously taught. The suppleness of the body?s movements did not always require the spine to be erect, and Ma's teaching methods were excellent to open the joints. The hand and weapons sets could also be practiced slowly combining softness and hardness, as well as rapidly and explosively.

Taoism and Internal Power

Master Gao already had substantial exposure to so-called internal systems through his 10 year study with Su Taihe, a Taoist master living in Shanxi. Su was even taller than Gao, and spent much of his time in meditation and internal practice. His tall, thin appearance and traditional clothes made him appear like the old Taoists of previous generations. Master Su specialized in a system similar to Taijiquan and Wudanquan which, while done slowly and softly required substantial flexibility and balancing skills. Gao also learned Shanxiquan, a long fist style found in Shanxi from Su, (with some movements suggestive of Tongbei Fanzi and Pigua), and Jidong Pai, an internal system from Shandong, in which Su excelled. Gao also learned Master Su's push hand methods, and he assisted Master Su in demonstrating them for the government's All China Survey of Traditional Wushu masters in 1982.

During his university years Gao was particularly drown to the internal practices of Ma's systems and the use of the whole body to generate power. Gao also began to feel that modern Wushu was less satisfying for him to practice and began again to concentrate on traditional systems, even while at Xian Tixue. Gao later went on to become All China Champion in Tongbei and Fanzi in 1983 and 1984.

Championships, Teaching and Movies

Gao describes the differences between traditional Wushu and modern Wushu using the metaphor of calligraphy. Modern Wushu is more like the printed word: standardized, clean and precise, but lacking the "feeling" of hand-written calligraphy, which can be executed with numerous variations evoking different moods and expressions. In addition, traditional martial arts have direct applications to fighting and self-defense, as compared to modern Wushu which puts the stress on artistic expression. There is also an age factor in modern Wushu, and few individuals can continue to compete at an elite level, above the age of 30. All of Gao's traditional masters could still vigorously practice well into old age. While there are exceptions to the rule, Gao feels the longevity factor is very important to cultivate in one's practice.

Gao describes the differences between traditional Wushu and modern Wushu using the metaphor of calligraphy. Modern Wushu is more like the printed word: standardized, clean and precise, but lacking the "feeling" of hand-written calligraphy, which can be executed with numerous variations evoking different moods and expressions. In addition, traditional martial arts have direct applications to fighting and self-defense, as compared to modern Wushu which puts the stress on artistic expression. There is also an age factor in modern Wushu, and few individuals can continue to compete at an elite level, above the age of 30. All of Gao's traditional masters could still vigorously practice well into old age. While there are exceptions to the rule, Gao feels the longevity factor is very important to cultivate in one's practice.

After winning his national titles, Gao was appointed as a coach for the Shanxi provisional Wushu team. He was also named All-China Coach of the Year in 1984, as many of his students went on to win provincial and national championships. Part of Gao's responsibilities as a coach and official was to judge at many of these competitions. During a masters demonstration Gao was approached by a film director who asked him if he was interested in acting in the movies. He always excelled at projecting his emotions and enthusiastically accepted the movie role.

Gao's first acting role was in The Secret of Taijiquan in which he starred as a general, murdered by the Manchu leadership, whose sons go on to avenge their father's death after learning Taijiquan. Gao?s movie career began to blossom and he acted and starred in over 30 movies and television productions. Subsequently, with his success, Gao left his full-time coaching job to pursue a career in films. Despite his rising fame and recognition as an actor in China, Gao continued to teach, and produced many gifted students who went into film work as well as into the sports institutes, the police and security forces. Gao also spent time with Ma?s blessing, training the Chinese special forces and national police in Xian in hand to hand combat, between his movie roles. Due to his skills and screen presence, Gao began to get international offers to appear in overseas films, and decided to relocate to the U.S.A. He was given permanent residency in the USA under the classification of "exceptional person," certainly one of the very few martial artists to be immediately granted permanent residency status in the category.

America and Ang Lee

It was in the U.S.A. that Gao first met Ang Lee, the famous director from Taiwan, and they became good friends. "Ang had been interested in Chinese martial arts since childhood," says Gao. Although he had never seriously studied martial arts, Ang Lee was looking for a teacher, and subsequently requested Gao to teach him and his children. Ang Lee had always wanted to do a martial arts film based upon classical themes. According to Gao, Ang wanted to immerse himself in Chinese martial arts in order to capture its essence, as part of his preparation for making such a film.

It was in the U.S.A. that Gao first met Ang Lee, the famous director from Taiwan, and they became good friends. "Ang had been interested in Chinese martial arts since childhood," says Gao. Although he had never seriously studied martial arts, Ang Lee was looking for a teacher, and subsequently requested Gao to teach him and his children. Ang Lee had always wanted to do a martial arts film based upon classical themes. According to Gao, Ang wanted to immerse himself in Chinese martial arts in order to capture its essence, as part of his preparation for making such a film.

Lee and Gao shared a similar vision about making films in this genre, and Lee was impressed by Gao's skill, artistic vision, and by his experience in the Chinese film production industry. Ang Lee realized that any real fighting, utilizing authentic, traditional kungfu was not particularly cinematic, as real fighting usually ends in a very short period of time. He still however, wished to present traditional kungfu in an artistically stylized setting and chose a Qing dynasty novel by Wang Dulin as a basis for his project. The result would be Academy Award winner Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Ang also had never made a film on the Mainland and asked Gao to come to China and help him with the pre-production planning needed for such a project. In the spring and summer of 1999 Gao spent time in China helping Ang choose locations, actors and assemble the production team. Ang engaged the great Yuen Wu Ping and his team to create as the martial arts choreography for the project.

But it fell to Gao, because of his martial arts film background and skills as a trainer, to condition the principal cast members, note their particular strengths and deficiencies, and to develop the individual movements for the fighting sets that were created for in the movie. This was a formidable task, as few of the cast members were trained martial artists, and although Michelle Yeoh had done martial arts movies, and both she and Zhang Ziyi were dancers by training. "It was necessary that the fighting sets have a traditional flavor, and Ang wanted the movements of each actor to evoke the personality of the specific character portrayed," says Gao. As Gao stated in an interview in the New York Times, Zhang's character is young and impulsive and her sets contained lots of aerial movements portraying her as if she could "fly," while Michelle's character was that of mature, seasoned martial artist who is rooted, and wanted to pull her opponents down to the earth.

The film, Ang felt, should also not be a typical action movie and had to remain true to higher artistic themes. Gao noted that teaching actors to execute movements for a film is quite different than teaching other typical martial arts students. Gongfu, after all, requires time and work, and, while actors work very hard to learn a movement and portray a role in a relatively short period of time, training martial artists cannot be achieved so quickly. Martial arts students must also inculcate underlying martial arts ethics, and acquire a deeper level of practice and understanding. This cannot be achieved in a short period of time, especially if one is to retain that knowledge for the rest of one's life.

Gao's main interests are still those of a martial artist and teacher. "One usually cannot expect to obtain role after role, as most actors are not always working. If the proper role comes along, one can accept it, but if it doesn't, one must accept that too." Gao has several schools in the New York area, and continues to teach students a multifaceted training based upon the many systems he has studied. After learning the basic curriculum, students may learn Pigua, Fanzi, and Tongbei or other systems which are considered advanced training. Gao notes, "These advanced systems are very difficult for most students to do properly, as they require a lot of basic training before one is able to learn them. That is because one must possess significant suppleness and a high level of aerobic training in order for one to remain soft, while executing the rapid power movements of these systems." If one's body is tight and hard, the muscles and joints are "dead," stopping efficient speed and power. The key to power is thus "softness," not "hardness." Most important for Gao, however, is the development of the students' internal spirit, enabling them to express the "taste" of each system. This allows one to develop real kungfu, as the movements themselves are secondary to one's intention and spirit expressed outwardly. "This is what one can practice for the rest of one's life," says Gao, and that is really what Xian Gao is about.

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2002 .

About

Bob Feldman :

Bob Feldman is a physician and martial arts writer who has written many articles over the past decade. He has also won several national rankings in a variety of Chinese martial arts.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article