Click here for Chinese New Year 2018: Year of the Dirty Dog

If 2018 was The Year of the Dirty Dog, you may well wonder why 2019 is the Year of the Dirty Pig. The Chinese annual zodiac has twelve animals in the following order: Rat (Shu 鼠), Ox (Niu 牛), Tiger (Hu 虎), Hare (Tu 兔), Dragon (Long 龍), Snake (She 蛇), Horse (Ma 馬), Ram (Yang 羊), Monkey (Hou 猴), Rooster (Ji 雞), Dog (Gou 狗), and Pig (Zhu 豬). Dog and Pig are at the end of the zodiac, but that’s not why they’re dirty. It’s their element. On top of the twelve zodiacs, there are five elements: Wood (Mu 木), Fire (Huo 火), Earth (Tu 土 ), Metal (Jin 金), and Water (Shui 水) – again in that order. These Five Elements are superimposed on the twelve zodiac for a Cycle of Sixty (5 x 12 = 60), although each element is repeated twice, the first year being Yang and the second year being Yin. Got it? So, here’s a math problem – if the first year of the present cycle started in 1984 with a Yang Wood Rat, what number year would this be in the cycle and is it Yin or Yang? The answer is at the end of this article, but I’ve already given you a hint – it’s the Year of the Dirty (earth) Pig.

There are myths explaining the procession order of the Chinese zodiac animals. Depending on the version, all the animals are summoned to either a heavenly banquet hosted by the Jade Emperor, or to the Buddha as he lay on his death bed. In both accounts, the pig is last because pigs are lazy. Over the last few years, I’ve taken to writing about the Zodiac on Chinese New Year, mostly to sell our annual T-shirts and hoodies. So if you’re feeling lazy and don’t want to learn some fun facts about pigs, just buy your Year of the Pig T-shirts and hoodies now. And while you’re at it, if you aren’t already subscribed, please subscribe to Kung Fu Tai Chi. Now some fun facts.

Fun Fact: There really isn’t a Pig style of Kung Fu. That has always bothered me. There’s a Kung Fu weapon associated with pigs and I’ll get to that later here. Like in Europe, pigs have been domesticated in China for centuries and often served as sacrificial offerings. Swine, like any meat-providing animal, is looked down upon because if we held them in high regard, like say dogs and cats, we wouldn’t eat them. In English, we even disguise the names of animal meats to make the distinction even clearer, so chickens are poultry, cows are beef, and pigs are pork, ham or bacon. Even deer meat is called venison, and it's not like there's venison burgers to be found at the local fast food joint. It’s more honest in Chinese. To distinguish meat, the character rou (meat or flesh 肉) is added, so it’s chicken flesh, cow flesh and pig flesh (jirou, niurou, or zhurou 鸡肉, 牛肉, or 猪肉). And while many Americans are put off by having the head of the chicken, fish or duck served up at banquets, Chinese cuisine demands it. Chinese know that without the head, anything can be hidden in a nugget.

While the farm pig is frequently looked down upon as a lowly porker, the wild boar is recognized for its ferocity and tenacity. Boars are respected in African and European cultures as a warrior animal. We find boars appearing in European heraldry as emblems on coat-of-arms, and even on a few regional flags. In Europe, particularly Germany, Belgium and the United Kingdom, the boar is prized as a symbol for a fierce fighter.

I came face to face with a boar in the wild once when I was very young and I can tell you firsthand that they are ferocious. I was camping at a local park with my father and cousins, sleeping in one of those ridiculous old-school tube tents, when some wild boars entered our camp. We woke to them rooting about and snorting. We were dumb campers and left some fish out that we had caught earlier. I remember looking up while lying prone in my dumb tent and making eye contact with one of the boars. If that boar charged, I was done. It was low to the ground, evolved to shred me with its tusks, and built to charge. I was wrapped like a cocoon in my sleeping bag, further restricted by my tent which was essentially a tubular tarp of restriction. If the boar wanted, it could’ve shot through my tube tent like a ball through a cannon. It was one of those camping epiphanies, one that any camper learns early – respect nature.

I learned later that boars aren’t even indigenous to my state. They are a hybrid species, the product of European wild boar brought to Monterey in the 1920s and formerly domestic swine, also imported by the Europeans back in the 1700s. Enough of those swine escaped and went feral, and then they mated with the wild boars that came a century ago to produce a unique crossbreed, the California wild pig.

More Fun Facts: Pigs are actually fairly similar to humans on many levels. We share the same dentition as pigs, which is a fancy way to say that our teeth are alike. While humans don’t have tusks, both pigs and humans have incisors, canines, bicuspids and molars and are diphyodont, which is another fancy word. Diphyodont means we both have baby teeth and lose them to make way for adult teeth. This means we eat the same things, more or less, or at least we would in the wild. Not only that, but it is said that we taste the same. Another Fun Fact: Cannibals from the Pacific Islands referred to human meat as ‘long pig.’ And if that isn’t enough Fun Facts, pig sexual pheromones are allegedly akin to human pheromones, so much so that some unscrupulous companies have repackaged the industrial pig pheromones used in farming for artificial insemination as sexual attractants for humans.

Okay, that was too much information, too many facts. And I digress. Buy your Year of the Pig T-shirts and hoodies to rock the greatest Chinese pig of all, Pigsy.

The Warrior Pigsy

When it comes to Pigs and Chinese Martial Arts, there’s one legendary hero that any Chinese, or literate sinophile, will cite – Pigsy. Pigsy is part of a quartet of heroic pilgrims from the beloved 16th century Chinese epic Journey to the West. His Chinese name is Zhu Bajie (猪八戒). As I’ve said already, Zhu means Pig. Bajie means ‘eight austerities,’ which refers to Buddhist precepts. Pigsy was originally the Curtain-Lifting Marshal in command of 80,000 Heavenly Navy Soldiers, but he got drunk at a Heavenly party and tried to seduce the Moon Goddess, Chang’E. For his sins, he was cast down to Earth. Unfortunately, he couldn’t find a human womb to reincarnate, and instead wound up in the womb of a sow. He ate his way out of his sow mama’s womb, and consequently became obsessed with eating humans…or long pig.

In Journey to the West, Pigsy is the comic relief, the Id opposite of the Superego Buddhist Monk Xuanzang, with the main hero, the Monkey King Sun Wukong, stuck in the middle. Pigsy is a slothful glutton, stereotypic of his species. How often have we heard "lazy pig" or "fat pig"? Pigsy is also lustful, a serial sex offender, never learning from his crime or his punishment for harassing the Moon Maiden. Pigsy is petty, very jealous of the Monkey King, and often acts out of envy.

In contrast, Pigsy is also merciful and optimistic. He often gets the quartet in more trouble by pleading for the lives of adversarial demons that later come back to haunt them. He’s also a great fighter, although he will run from a fight when given the chance. When a battle breaks out, Pigsy exclaims some excuse, like needing to ‘take a shit,’ and then hides for the duration of the fight (Note that ‘shit’ is literally how W. J. F. Jenner translated the prose for one of the most prominent English versions). Nevertheless, like that wild boar, Pigsy is a fierce fighter, and like many heroes of Chinese legend, he wields a signature weapon, his Nine Tooth Spiked Rake (jiu chi jing pa 九齒釘耙).

There’s an entire class of martial arts weapons that evolved from farming tools, which stands to reason because most civilians had to use whatever was at hand back in the day. What’s more, if they were farmers, they knew how to use their tools. The most conspicuous farming tool weapons are in Japanese Budo, specifically the Nunchaku, Kama, Sai and Tonfa. Analogous and prominent farming tool weapons in Kung Fu include Whips, Spades and Forks. These weaponized versions are highly extrapolated from the original agricultural tools, but they still sit well within the category.

Pigsy’s Rake is exceptional and unconventional. It was forged by Laozi, the author of the seminal Daoist tome Daodejing (more widely known by the old spelling Tao Te Ching) and has teeth of jade. However, beyond Pigsy’s implement, the Rake is seldom seen used as a weapon in any martial culture. Subsequently, almost all Kung Fu Rakes have nine points in homage to Pigsy. Some have outlandish arrangements of points while others are rather mundane and look like they might actually function as a working rake.

Kung Fu Rake forms are rather rare nowadays. Perhaps they started from Traditional Chinese Opera where retellings of chapters from Journey to the West are spotlighted. Maybe they are descended from farming, but generally speaking, the designs of the rake head are too fanciful to be practical. In this way, it is very reminiscent of the Spade. The Monk Spade, or more formally Moon Tooth Spade (yue ya chan 月牙鏟), is also a weapon from Journey to the West, carried by another member of the pilgrim quarter, Friar Sandy.

While it may seem coincidental that both Pigsy and Sandy have weapons named after teeth, it’s important to note that they are different in Chinese. Ya (牙) means teeth, more specifically incisors, canines, bicuspids and molars like what we humans share with pigs. It also can mean ‘serrated.’ Chi (齒) means teeth too, but it refers more to the teeth of cogs and gears. Just like many Kung Fu versions of Pigsy’s Rake, Sandy’s Spade is impractical for digging. But that’s another story, one that we’ve already told in our 2012 Shaolin Special (May+June) cover story, "The Spade, the Whip and the Mountain Gate".

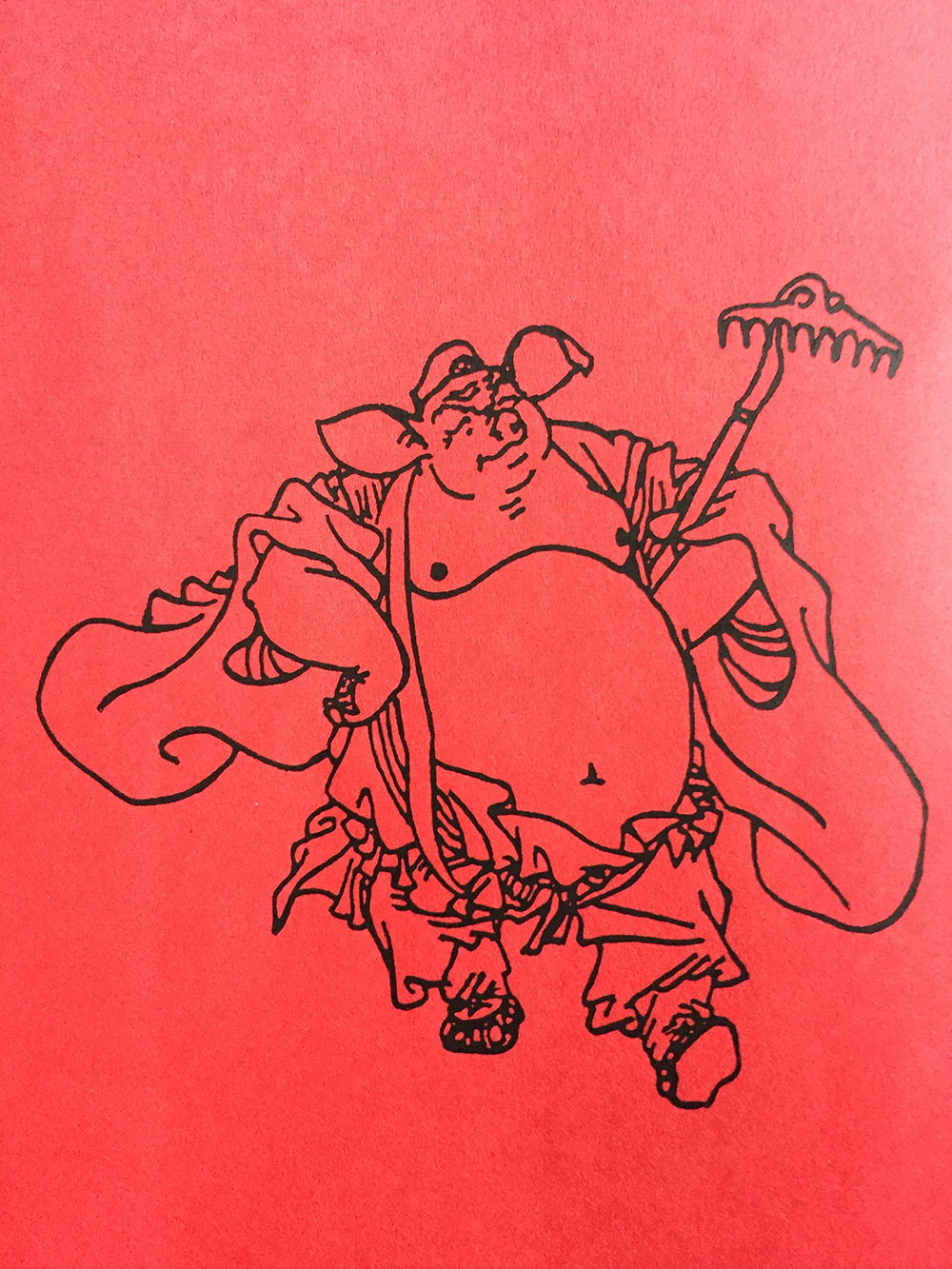

Back before the interwebs, I made postal greeting cards for Chinese New Year, so nearly a quarter century ago (two dozen years to be exact – two cycles of twelve), I did one of Pigsy for the Year of the Wood Pig. I drew Pigsy by hand, copying it off an image I found in a book, and made sure to count out nine teeth spikes for his rake. I’m sharing that here because I can, having kept that greeting card on file, apparently just for the occasion of this article.

Pigsy is a favorite because he’s a hero by circumstance and would probably have been much happier if left alone. He doesn’t seek fame or glory, or even that much justice. He just wants to eat, sleep, shit and molest moon maidens. There’s an honesty to his character and it’s one that many actors have taken on with the many varied interpretations of Journey to the West.

The esteemed Hong Kong filmmaker Stephen Chow tackled Journey to the West several times. He released A Chinese Odyssey Part One: Pandora's Box and A Chinese Odyssey Part Two: Cinderella back to back in 1995. Ng Man-Tat, a frequent collaborator of Chow’s, played Pigsy in those. Also, although Mad Monk (1993) wasn't explicitly Journey to the West, Chow borrowed heavily from the classic. In 2013 Chow wrote, directed, produced and choreographed Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons and in 2017 he produced Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back. Chen Bing Qiang played Pigsy in the first installment, and was replaced by Yang Yiwei in the second. Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons was the highest-grossing Chinese film of its time. Chow’s films are all parodies, and not particularly loyal to the original story, although it should be noted that there are several versions of Journey to the West. The tale descends from a tradition of storytelling revised to provide commentary on current affairs, so it’s meant to be passed down literally. In 2018, Chow announced he was helping Pearl Studio develop a new animated film based on the Monkey King. Pearl Studio arose from DreamWorks Oriental, which co-produced Kung Fu Panda 3 (2016).

Beyond Chow's upcoming film, there are many other current interpretations of Journey to the West running now, and consequently, there are many takes on Pigsy. On the big screen, Director Cheang Pou-soi has delivered three installments of Monkey King in 2014, 2016 and 2018. The last two films introduced Pigsy, played Xiao Shenyang. These films are fairly loyal to the original novel, and Xiao captures Pigsy well with one of the most authentic cinematic interpretations of the character.

On the small screen, Journey to the West has gone abroad and the diaspora has diverged dramatically from the original source material and evolved into various unique storylines. A Korean Odyssey (a.k.a. Hwayugi) was a 2017 sitcom that placed Monkey, Pigsy and the rest of the characters in the modern world, with magic. Pigsy was played by K-pop star Lee Hong-gi and named P.K., or by the Korean transliteration of Zhu Bajie, Jeo Pal-gye. In this modern setting, he works for Lucifer Entertainment and he can seduce women by sorcery. A Korean Odyssey was well received, earning the most-watched premiere in its time slot. In 2018, Television New Zealand and the Australian Broadcasting Company co-produced The New Legends of Monkey with Netflix. Set in a fantasy world of sword and sorcery, Josh Thompson adopted the role of Pigsy. The series received heavy criticism for whitewashing and cultural appropriation because none of the cast were Asian.

Nick Frost photo courtesy of AMC and Into the Badlands.

The most notable current take on Pigsy is in AMC's Into the Badlands. Beginning in 2015, the top-notch fight choreography of Into the Badlands earned it a cover story in our JAN+FEB 2016 issue of Kung Fu Tai Chi and ample additional coverage. Set in a post-apocalyptic future, the story is only marginally inspired by Journey to the West with Daniel Wu playing Sunny (a derivation of the Monkey King's name Sun Wukong) and Aramis Knight as M.K. (an abbreviation for "monk"). Season Two introduced Bajie, portrayed by none other than veteran comedic actor, Nick Frost, and he captures the spirit of Pigsy astoundingly well. I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing Frost twice for Into the Badlands. “I got to play him as me essentially. He's kind of a heightened, more aggressive version of me,” said Frost in our interview INTO THE BADLANDS: Enter the Pig. Despite being the farthest of any TV interpretation, Frost captures the spirit of Pigsy well. “I'm a brawler. I'm a wrestler. I'm a spiteful fighter. I'll throw sand at you. He's one of those guys. He's a prison fighter. He will literally pick anything up and pop someone over the head. He's a survivor.”

Sad Fact: the Year of the Dirty Pig brings along something dreadful to survive – the H1N1 virus, also known as Swine Flu. It was declared a pandemic a decade ago, claiming a whopping 17 thousand lives, but the pandemic was considered over by 2010. There have been spotty outbreaks ever since, India in 2015, Maldives and Myanmar in 2017, and African Swine Flu rose to threatening proportions last year. This January began with 73,000 farm pigs infected with African Swine Flu on a huge factory farm in Heilongjiang Province. It was the largest case in China, which has already seen nearly a hundred farms contract the virus, and drastic measures are being taken to prevent further spread. We shall see what toll the Year of the Pig brings.

Sad Fact: the Year of the Dirty Pig brings along something dreadful to survive – the H1N1 virus, also known as Swine Flu. It was declared a pandemic a decade ago, claiming a whopping 17 thousand lives, but the pandemic was considered over by 2010. There have been spotty outbreaks ever since, India in 2015, Maldives and Myanmar in 2017, and African Swine Flu rose to threatening proportions last year. This January began with 73,000 farm pigs infected with African Swine Flu on a huge factory farm in Heilongjiang Province. It was the largest case in China, which has already seen nearly a hundred farms contract the virus, and drastic measures are being taken to prevent further spread. We shall see what toll the Year of the Pig brings.

Remember to get your Year of the Pig T-shirts and hoodies now. Gung Hay Fat Choy! Gong Xi Fa Cai! 恭喜發財!

The ANSWER: 2019 is the 36th year of the Cycle of Sixty, the Yin Earth Pig. That math is actually really easy. Subtract 1984 from 2019 and you get 35, then add 1 because 1984 counts as one so you get 36. And it’s Yin because all odd years are Yin. That’s odd. Then it’s Yin.

About author:

Subscribe to KungFuMagazine.com here.

Reserve your print edition of the WINTER 2025 here.

Gene Ching is the Publisher of KungFuMagazine.com and the author of Shaolin Trips.